“The man who throws a bomb is an artist,” says Lucian Gregory, one of the poets who reside in the suburb of Saffron Park in The Man Who Was Thursday by GK Chesterton. “I would destroy the world if I could.” In The Intellectuals and the Masses — a book guaranteed to traumatise any devotee of Modernist literature — the scholar John Carey highlights Chesterton’s novel as an example of early twentieth century English writers’ attitudes towards suburban living. Carey suggests that Chesterton’s sympathies lie with the other poet of the story, Gabriel Syme, and his innate respect for law, order and responsibility, and who believes the underground railway to be “the most poetic thing in the world”. Order vs. disorder: which is the more aesthetically beautiful? Which is the more important for art? The consensus today, from the Futurists to the Chapman brothers, would seem to be that art should tear down taboos, that it has an obligation to challenge or even shock.

But is our faith in art’s power merely an illusion and a dangerous one at that, concealing the real function of art in society? Herbert Marcus, doyen of the New Left in the West, offered a cautionary analysis of art’s role with his 1937 essay, “The Affirmative Character of Culture”. In it Marcus is decidedly pessimistic about culture’s capacity to revolutionise society. While it was not impossible for art to incite audiences to revolution, by its nature culture affirmed the existing social order. Far from being an instrument of dissent, it helped people to endure the status quo.

In the later “Art and Revolution” (1972), Marcuse describes the double bind of provocative and experimental art then in vogue that at once transforms audiences and also unites them as a mass attending a spectacle of hysteria. “It is, moreover, another case of catharsis: group therapy which, temporarily, removes inhibitions. Liberation remains a private affair.”

What can artists do? They have to engage directly. “Art can do nothing to prevent the ascent of barbarism,” says Marcuse. “It cannot by itself keep open its own domain in and against society. For its own preservation and development, art depends on the struggle for the abolition of the social system which generates barbarism as its own potential stage: potential form of its progress. The fate of art remains linked to that of the revolution. In this sense, it is indeed an internal exigency of art which drives the artist to the streets — to fight for the Commune, for the Bolshevist revolution, for the German revolution of 1918, for the Chinese and Cuban revolutions, for all revolutions which have the historical chance of liberation. But in doing so he leaves the universe of art and enters the larger universe of which art remains an antagonistic part: that of radical practice.”

There has been a recent surge in interest in Japan’s post-war art trends, some of it very belated indeed. Following on from domestic and international exhibitions devoted to Gutai and Mono-ha, as well as the big group shows such as “The 70s in Japan” (covering 1968-1982) at the Museum of Modern Art, Saitama, and of course the huge MoMA show, “Tokyo 1955-1970: A New Avant-Garde”, “Hi-Red Center: The Documents of ‘Direct Action'” now comes to the Shōtō Museum of Art in Shibuya, a most appropriately Showa-feeling building. This exhibition was previously at the Nagoya City Art Museum in late 2013 and commemorates the formation of the eponymous experimental art unit fifty years ago.

Hi-Red Center’s name derives from the English translations of the first characters of the three founding members’ surnames (Jirō TAKAmatsu, Genpei AKAsegawa, Natsuyuki NAKAnishi). Along with Zero Jigen, the unit was arguably the most impressive avant-garde Japanese group of its kind in the early 1960s. Since Hi-Red Center’s output was dominated by stunts and happenings, many of the exhibits are reduced to being photographic records, though it is still quite something to seeing them all together to assess how fresh and bizarre they would have seemed at the time.

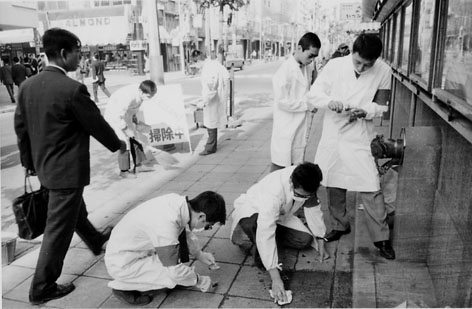

For example, in 1963 a pedestrian in Tokyo might have been shocked to see Natsuyuki Nakanishi, walking around central Tokyo with clothes pegs attached to his face, like a kind of mad domesticated version of Kōbō Abe’s The Box Man. More directly critical and caustic, though, was the group’s attempt to “clean” the streets of Ginza. Wearing lab coats and carrying brooms, the Hi-Red Center team set about “beautifying” the pavements of the fashionable district in protest at the government’s drive to clean up Tokyo ahead of the Olympic Games. This was the post-Anpo era, a time of healthy cynicism towards the government after it had failed to heed the protests against the renewal of the Japan-US security treaty. At its peak the protests saw half a million people on the streets and a young female demonstrator was killed in June 1960. It set the scene for both the anger of the New Left and student movements to come later in the 1960s and also the anti-Establishment flavour of the arts throughout the counterculture period.

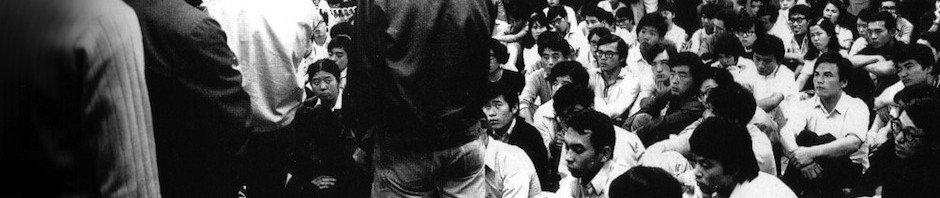

1963 also marked the final year of Yomiuri Indépendant, the annual exhibition which had become the unofficial pastureland for experimental artists to indulge in the whimsies of their work. Nakanashi showed an installation of his clothes pegs promenade. Jirō Takamatsu caused more of a stir when his work was literally unwound, stretching out of the Ueno venue and through the park and ending at the station. While so much of art in Japan is buttoned up in white cubes, Hi-Red Center were taking their experiments out on the Yamanote Line, throwing objects off the roof of an Ikebukuro department store, or “closing” a gallery for one exhibition. These were forms of “direct action” (chokusetsu kōdō). The Yamanote Line event had been a ritualised, shamanistic experiment in occupying the public commuting space, agitating the fellow passengers to be witnesses to the catharsis they were creating with strange objects and white face paint.

Shelter Plan, on the other hand, was conducted in more snug and deluxe environs. The artists took over a room in the Teikoku Hotel in Tokyo and invited a veritable Who’s-Who of folk from the bohemian and artist scene at the time. Guests were then measured for a tailor-built evacuation shelter that they had the option to purchase in a range of sizes. Absurd, yes. But then how else should one respond to the threat of nuclear apocalypse? As curator Doryun Chong has said: “Hi-Red Center’s work could be read as a brilliant, absurdist parody of the control exerted by the state on the citizenry in an increasingly controlled society.”

Nakanishi and Takamatsu already knew each from the Tokyo University of the Arts; Genpei Akasegawa came separately to the group. Akasegawa had previously worked alongside other leading experimental artists from the era in the Neo Dadaists. His legacy has proven stronger than Nakanishi and Takamatsu’s, though, partly thanks to his manga and illustration work, as well as later prolific non-fiction writing about art, but surely most of all due to the thousand-yen bill counterfeiting scandal. It arose after Akasegawa hired a printer to reproduce 1,000 yen bills. These obviously fake items were used as invitations for a show but the artist was still questioned by police, and eventually indicted in 1965 under a 1895 law against “imitation”. The subsequent court case dragged on until 1970 where it was as if art itself was on trial. Was it acceptable to create reproductions that challenged state authority and violate the law in the name of expression? Ever the iconoclast, Akasegawa used the case as material for more artworks with 1,000-yen note motifs. The discourse and prosecution were turned into further forms of expression. Ultimately what Akasegawa was engaging in here was more “direct action”.

In April 1970, the Supreme Court upheld Akasegawa’s guilty verdict and sentence, ensuring his notoriety and the Establishment’s bewilderment in the face of a changing artistic landscape. Some of Akasegawa’s later work was also recently included in “Roppongi Crossing 2013: Out of Doubt” show at the Mori Art Museum. This jarred not only for its temporal incongruity but also its spiritual disparity. In contrast to the contemporary work showcased in the exhibition, Akasegawa’s manga art included direct and mordant references to the political scene from the time, from Sanrizuka to the uchi-geba of the various New Left factions that veered from name-calling to horrific violence.

One of his pictures at the Mori show, an epic chart of the militants in the landscape of the early 1970’s called The Map of Democratic Empire of Great Japan in Year of 2632 of the Imperial Era, recalls George Cruikshank’s The Worship of Bacchus. Next to it was a startling image of an airplane, piloted by a riot police officer and with two passengers, one of whom is a horse. The main slogans in a speech balloon read “Worship at Sanrizuka!” and “Hijacked from Sanrizuka!” It was from Sakura-gahō, Akasegawa’s manga in the early 1970’s and here highlighting a major counterculture festival taking place at Sanrizuka during the height of the airport protests.

The curators were pointing to a “genealogy of nonsense” that went from the post-war through to the contemporary scene, though what stuck out the most was simply the difference in candour in the largely lackadaisical offerings of the younger artists. In this sense, “Roppongi Crossing” took a typical foreigner’s perspective (two of the curators were non-Japanese), forcing lines between local historical dots. Sometimes this lends surprisingly and perceptive results. This time, I wasn’t convinced. It fundamentally didn’t work because the post-war material was so much more caustic and, being confined to a single room at the start, was bereft of real context. It felt more tagged on than a genuine parallel or perspective laid out over the whole of the exhibition.

It also did not work because the majority of the contemporary works were not even really responses to 3.11 nor were they political. Ichirō Endō’s everyone-just-smile-and-be-merry output has been cringeworthy for years; when put alongside the urgent themes of Fukushima or the 1950s and 1960s, it is insulting to all concerned. The few contemporary works that were actually politicised had a different tone to Akasegawa et al.

While the curators’ mission was worthy and valid enough, the unintended effect was to show how far Japan has changed as a society. Now the artists would appear to be at best reflective and analytical, at worst childish and facile. Yoshinori Niwa’s contribution featured him interviewing members of the Japanese Communist Party and expressing his confusion about the party’s current stance of democratic parliamentarianism. It might well be a deliberate performance of ingénue on Niwa’s part, or else presumably he does not (or did not) understand the difference between Marx’s theories and revolutionary politics, let alone the basic post-war history of the JCP. Perhaps he is being quietly satirical and suggestive? If the most interesting exploration he can offer, though, is to film himself asking questions to JCP officials, presenting them with a picture of Marx, and walking around London in search of the man’s tomb, then things are not moving forward enough. An artist should be offering much more than this.

The members of Hi-Red Center were humorous and nonsensical, yes. But they were also committed, serious and formally inventive. To return to Marcuse and “Art and Revolution”: “…the radical effort to sustain and intensify the ‘power of the negative,’ the subversive potential of art, must sustain and intensify the alienating power of art: the aesthetic form, in which alone the radical force of art becomes communicable.” Without form, you have only onanism. A more successful example from “Roppongi Crossing 2013” in terms of historical continuity and stylistic experimentation was Takashi Arai’s series of daguerreotypes. Henri Becquerel, whose name is lent to the Bq unit of measuring we have all become so familiar with since Fukushima, was able to observe spontaneous radioactivity through experiments with phosphorescent substances and Lumière photographic plates. Arai’s daguerreotypes highlight this unsettling relationship between history, radiation and photography through images of nuclear sites like Fukushima and Hiroshima. While it is frustrating to see yet more simplistic correlation between nuclears of war (Hiroshima) and energy (Fukushima), visually Arai’s images were effective. In particular, his series of daguerreotypes for Multiple Monument for Daigo Fukuryū Maru Lucky Dragon 5 (2013) stood out like memento mori in the darkened exhibition room. The title is a reference to the Daigo Fukuryū Maru, a Japanese tuna vessel caught in the fallout from a US nuclear bomb test in 1954.

“Hi-Red Center: The Documents of ‘Direct Action'” is a fairly modest show and is presented almost entirely without explanation or background, a curatorial choice likely to leave uninitiated visitors mystified. However, given the recent flurry of academic books, readers looking for more in English can sate their appetites with Money, Trains, and Guillotines: Art and Revolution in 1960s Japan by William Marotti (2013), Tokyo 1955-1970: A New Avant-Garde by Doryun Chong (2012), Experimental Arts in Postwar Japan: Moments of Encounter, Engagement, and Imagined Return by Miryam Sas (2011), or Radicals and Realists in the Japanese Nonverbal Arts: The Avant-Garde Rejection of Modernism by Thomas R H Havens (2006).

And having reviewed the work of past artists, the question now remains whether those of the present or the future will set about cleaning the streets when the 2020 Olympics come around. Participants in the “Roppongi Crossing” just closed and the next to come, please take note.

Hi-Red Center: The Documents of “Direct Action”

At the Shōtō Museum of Art

February 11th to March 23rd, 2014

WILLIAM ANDREWS

Great review. I am reading this now, as I am researching the Hi-Red Center’s degree of art activism in the sense of the contemporary conception of the term.

However, I have one critical remark to make. I don’t think to draw a connection between the “nuclears of war” and nuclear energy is simplistic. Both are part of the intricate mechanisms of the global nuclear regime and ultimately in the worst condition of their existence subjecting humans and the environment to the necropolitcs of radiation.

LikeLike

Thank you for your comment. Yes, this is somewhat divisive. My opposition stems from what swiftly became a cliché: placards and lazy op-eds equating Fukushima with Hiroshima and Nagasaki. I don’t dispute the connection per se. You can certainly draw a parallel between nuclear power and nuclear arms, though just not a simplistic one. The facilities for nuclear power can, of course, be used as part of the system for developing nuclear arms, but this is a more complex issue in terms of science, state infrastructure, and so on, and one which requires some subtlety to address and elucidate.

LikeLike

Thank you for your reply! Yeah they can not be equated just because they deal with the same “materials” (that’s what you mean by drawing a simplistic parallel right?). But besides both being part of a complex system of science, politics and so on, I was more thinking about the (post-apocalyptic) conditions nuclear arms and a nuclear meltdown can create for humans, animals and environment. Of course even then they are not exactly the same, but they are similar in regards to the invisible threat of radiation and the creation of an uninhabitable zone of exclusion.

“Placards and lazy op-eds equating Fukushima with Hiroshima and Nagasaki” This sounds very interesting! Would you be able to kindly point me towards some examples?

LikeLike

On equating Fukushima with Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Though no one was annihilated, the society that once functioned there was obliterated and will never be the same. For a time, the people that once existed there became like ghosts, dislocated from the forces that grounded them in that place. They were spread out across the country, rooming with family, strangers, or in shelters. They will eventually regain form, but certainly not like before.

LikeLike