The buzz in 2015 about SEALDs missed an important point about the student movement in Japan: you can praise its “revival” all you want — and there is a revival, as witnessed in post-SEALDs groups like T-nsSOWL, Aequitas, Public for Future, and the Constitution Youth Projects — but it remains nigh impossible to politick seriously on campuses at public or private universities in Japan.

During the peak of the protests against the security bills in autumn 2015, Zengakuren staged a brief strike at Kyoto University, barricading part of the campus. For their efforts, activists were arrested (though not indicted) and several students suspended. On the one hand, Clean, metropolitan students at the National Diet in nice apparel and spouting liberal values are venerated in the mass media. But on the other, young activists promulgating Marxist ideas and engaging in (non-violent) direct action is taboo. Before any well-meaning journo writes another piece about the “renaissance” of the student movement and politically engaged youth in Japan, they should take a trip down to the Ichigaya campus of Hōsei University, where students are locked in a battle with the college that predates SEALDs by many years. Along the way, dozens have been arrested and tried for various crimes, and yet it shows no signs of abating. Zengakuren continues its regular, declamatory protests at the entrance, always filmed and scrutinised by nervous university employees.

While the “Zengakuren” name has been claimed by many, the only functional Zengakuren group today is the one under the wing of Chūkaku-ha (Central Core Faction). Both Zengakuren and Chūkaku-ha may become immediate targets for the newly passed anti-conspiracy law. Though touted primarily as a necessary measure against the threat of terrorism, the ambit of the anti-conspiracy law is so wide that it potentially means citizens can no longer protest construction projects by holding sit-in demonstrations. This may have a profound effect on the Diet protests, where occupying the land has been a key element of the activities, as well as protests in Okinawa against US bases.

Not surprisingly, some o of the most vehement opposition to the bill came from Chūkaku-ha, which frequently finds its members arrested for minor infractions and knows the dangers of such easily malleable legislation. Condemned nationally and internationally as a “terrorist group”, Chūkaku-ha is undoubtedly going to face more intimidation in the run-up to the Olympics in 2020.

Three Chūkaku-ha unionists in Kansai were arrested in May for trespassing, even though they were essentially just giving out leaflets. Incredibly, they were charged and the bail set at 3 million yen each. Another activist was arrested on June 12th by Shizuoka police on allegations of fraud related to welfare benefits, only to be released without charged on June 16th.

These incremental examples of state pressure on the group have passed under the radar of the mainstream media, though the same cannot be said about the sensational response to the police announcement in May of the arrest of a man believed to be Masaaki Ōsaka, the Chūkaku-ha activist on the run since 1972. Earlier this month, the suspect was officially confirmed as Ōsaka and re-arrested on a murder charge.

The media storm sparked by Ōsaka’s apprehension, including a surprising level of overseas interest, has ensured that Chūkaku-ha has stayed in the news headlines more than any time in recent memory, certainly in the years I have been monitoring the New Left in Japan and its legacy.

Police are now reported to be close to indicting their suspect, though the DNA “proof” that he is who they say he is may not actually stand up in court. (Update: Ōsaka was charged with murder on June 28th.) It is also only a matter of time before police raid Zenshinsha, the Chūkaku-ha headquarters, and start arresting activists they accuse of assisting Ōsaka during his long time on the lam.

Chūkaku-ha is often described as dating back to 1963, though this is only as far as the current faction’s birth. The complex lineage of the group, formally Kakukyōdō (Japan Revolutionary Communist League), has a pre-history that is older and connects to the origin of the New Left in Japan in the post-war years.

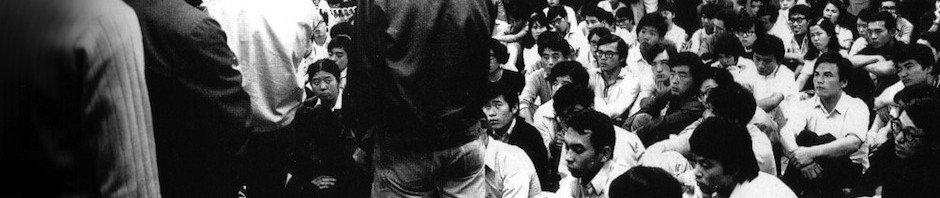

Generally considered notorious for its confrontations with the apparatus of the state and with another faction called Kakumaru-ha (Revolutionary Marxist Faction), Chūkaku-ha was one of the most prominent participants in the New Left and a leader of the student movement in the 1960s and 1970s. It advocated a mass movement towards a proletariat revolution, opposing Anpo (the US-Japan Security Treaty), the occupation of Okinawa and then the terms of its reversion, Japanese and American involvement in Vietnam, the construction of Narita Airport, and then neoliberal reforms and privatisation, especially of the railways.

Official police estimates of its membership vary, but sometimes are placed as high as 4,700, which would make it the largest far-left group in Japan. It is still treated as violent and dangerous by police, though today engages fundamentally in rank-and-file unionism and anti-war campaigning.

Since the new police crackdown started a few years ago due to increased student activism at Kyoto University and Hōsei as well as Chūkaku-ha involvement in the anti-nuclear power movement and on-the-ground activism in Fukushima, the group has reacted with efforts to present a more positive image to the media.

The charm offensive has recently unfolded online in the form of a better web presence, at least for Zengakuren, and even a series of YouTube videos, notably putting a female member, Tomoko Horaguchi, front and centre. Easy on the eye and a good public face for Zengakuren and Chūkaku-ha, Horaguchi is so popular she once even had her own fan site. It’s tempting to pinpoint this as the indirect influence of media-savvy SEALDs, which also positioned female members at the fore, but it is hard to say categorically.

Tomoko Horaguchi (left) being interviewed

Recently the Zengakuren activists at Kyoto University continued their opposition to the college and their efforts to reinvigorate one of the bastions of the student movement in Japan by holding a quasi-election on campus, collecting students’ votes to win legitimacy for a student council (that does not exist officially). Such self-governing student bodies were central to mobilising the student movement during the post-war years and were mostly controlled by various far-left factions. The past two decades and more have seen them dismantled by both public and private universities, furthering the decline of the student movement.

Zengakuren and Chūkaku-ha is also supporting the current election campaign of Kunihiko Kitajima in the Tokyo Metropolitan Assembly poll on July 2nd, though the news has been all about Governor Koike’s new party and predictions of a significant defeat for the LDP. Campaigning on a platform virulently opposed to the 2020 Olympics and the relocation of Tsukiji Market to Toyosu, Kitajima is standing for a seat as a representative of Suginami ward, an area with Chukaku-ha roots and where candidates have stood before (Kitajima was also once a member for the Suginami Assembly and Chukaku-ha has campaigned against the local closure of children’s centres). He and his supporters — including many Zengakuren activists — have been on the streets electioneering for some days now, dressed in a somewhat incongruously cute pink shirts as they give out leaflets and make speeches.

Election campaigning by Kunihiko Kitajima and Zengakuren supporters in Suginami

Mainstream media outlets have also been quite regularly allowed inside Zenshinsha to film and interview activists. A report broadcast on the online TV channel Abema TV on June 13th is the latest example. Abema TV previously did a show about the Asama-sansō incident and had two former members of SEALDs as commentators.

[The video is only online until July 13th.]

The piece is relatively neutral, zipping through the famous “terrorist” incidents (the attack on the LDP headquarters, the Skyliner train incident, the G7 summit attack, and so on) but devoting most of its length to material shot inside Zenshinsha. The Zengakuren activists interviewed reveal that the residents range in age from their twenties to their seventies. Of the inhabitants in their twenties, there are currently about ten, who form the core Zengakuren members (and several of whom I have met).

Outside Zenshinsha, a police camping van is shown always monitoring who goes in and out. Horaguchi puts on a mask before approaching. Even though they know who she is, and she knows that they know, she still does this as a small symbolic protest. Inside, there is heavy security with cameras watching for police or rightists as well as a double door system at the entrance. The corridors are also lined with photographs of suspected plain clothes police officers, so activists can know if they are being followed.

The maze-like base is filled with all manner of stuff, from giant printers to flyers, clothes and slightly ramshackle-looking electronics. But don’t let the veneer of dilapidation fool you: it’s no fluke that this group has been in operation since 1963. The activists know how to look after themselves and use their tools. The walls of the building are reinforced and repaired by activists to be earthquake-proof. There is even a bathhouse, which is open 24 hours a day to cater to activists always busy and working strange shifts.

The camera captures the head of Zengakuren, Ikuma Saitō, and another activist enjoyed a few drinks and relaxing. The interviewer tries to coax them to open up and talk about girls amid much laughter. But when the conversation is steered towards the anti-conspiracy law, the smiles stop and Saitō is adamant that they will continue to fight against state oppression.

Horaguchi, who is 28, wanted to be a nursery teacher or do something with kids, but the political bug came a-biting. It wasn’t a complete bolt out of the blue, though, since she actually comes from a family with links to Chūkaku-ha. She speaks with authority and prudence, yet also seems “normal”. What better spokesperson for Zengakuren to help shed its “extremist” image?

In the studio, commentators included a lawyer who has represented Chūkaku-ha and a former police officer as well as Nayuka Mine, a one-time porn star turned manga-ka. The ex-cop said that he thought there are far fewer than the estimated 4,700 members quoted in the report. He also compared the group to a cult or religion. This is all familiar mud that is so often thrown at far-left groups in Japan and elsewhere. The debate then grows more interesting when the subject turns to the nature of “violent revolution”: does it mean using violent means to achieve revolution, or does it mean that as you work towards revolution, inevitably violence occurs when you run up against the state?

The report ends with a viewer’s comments: “It’s a strange group. It’s like they are trapped in the last century.” Given the numerous comparisons that have been made between the new anti-conspiracy law and Japan’s pre-war draconian state, perhaps the previous century has returned.

WILLIAM ANDREWS

William, i absolutely devour every article you’re posting here. Great job as always, keep up the good work!

LikeLike

Thank you for sharing the video.

One mistake..

“The report ends with a viewer’s comments: “It’s a strange group. It’s like they are trapped in the last century.” should be “It’s like they are trapped in the 1970s.”

LikeLike

@Toru

Strictly speaking, yes, though it was intended as a free translation of the gist. The 1970s were, after all, in the last century.

LikeLike

Thank you for your reply. I was born in 1970s and my uncle was fighting against cops at Narita. He said he had no idea why he was fighting. He just felt like it and everyone thought it was cool. After the Asama incident, it was not cool anymore at all. Now he’s a normal office worker.

We don’t wanna go back to those days. Certainly not to pre-war period. One does not repeat same mistakes. So, don’t worry. We are OK. IF the gov’t try to shut me up, I’d fight for the right to freedom of speech to my death. But, the idea of “Violent revolution” to archive socialist state is a stupid idea in today’s Japan.

LikeLike

Love the writing and reporting on these political movements, keep it up!

LikeLike

@Sean Han Tani

Thank you.

LikeLike