Over the years I have continued to gravitate back towards the Shinjuku Station West Gate (Nishiguchi) protests, which I believe to be one of the most important yet little-known social movements in Tokyo today.

Every Saturday from 5pm to 7pm, demonstrators gather at the station area to protest against whatever issues they feel strongly about that week. They call it a “standing demo”; it is a kind of informal vigil, attended by a hard-core handful of liberal activists but also anyone who happens to turn up that weekend. There is no concrete co-ordination or rules other than the participants always gather outside the Odakyu Department Store above ground from 5pm to 6pm, and then from 6pm to 7pm below ground in the main plaza space outside the JR station ticket gates. They hold up or display placards, but that is all.

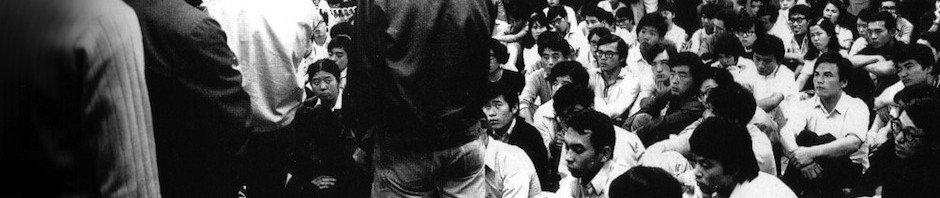

Of course, this movement, which has been going on since 2003 and is known as Shinjuku Nishiguchi Hansen Ishi Hyōji (新宿西口反戦意思表示, rendering slightly awkwardly into English as the Shinjuku West Gate Expression of Anti-War Intent), harks back to the famous West Gate “folk guerrilla” rallies that were led by Beheiren musicians. Starting off as anti-war concerts in early 1969, the weekly gatherings grew into immense rallies attracting thousands by the summer. Inevitably, they also attracted the police, who arrested the main musicians, forcibly expelled the participants and then blocked protestors from entering the underground plaza. The movement died out and could not repeat its success elsewhere, not least because the West Gate plaza was a surprisingly suitable venue: convenient and accessible, yet large enough for people to spread out and accommodate a range of different groups and also enclosed enough that it felt intimate and self-contained as a space.

The authorities notoriously reconfigured the “plaza” into a “passageway”, meaning that people could not stop in it. The movement was then historicised as an iconic episode in Japan’s “season of politics”. But this somewhat ossified status is no longer accurate. In addition to (and arguably, because of) the regular Saturday vigils, which are loosely led by Seiko Ōki, one of the original folk guerrilla musicians who returned to the site in 2003 to protest the Iraq War, the West Gate plaza has slowly started to re-acquire its former function as a public space facilitating citizens who want to exercise their right to the city in Tokyo.

After all, Japan is experiencing a period of liminality, in the Victor Turner sense of the word, and since 2011 has witnessed wave after wave of new social movements and practices. These have tested the (considerable) limits and restrictions placed on public space in Tokyo, giving birth, among others, to the long-running Kanteimae Friday night vigils outside the Prime Minister’s official residence protesting against nuclear power and the tents that occupied a plot of land outside the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry in Kasumigaseki for several years until their removal in 2016.

Within this current, Shinjuku Station West Gate has reappeared as a popular choice for speeches, rallies and other political stagings. The National Diet remains the most potent symbolic site — an anti-government rally by Sōgakari on 10 June against the Moritomo Gakuen cronyism scandal, for example, mobilised 27,000, despite heavy rain — yet the Nishiguchi plaza has practical advantages: it is underground, making it ideal in the June rainy season, and there is always an audience of passing pedestrians, shoppers and railway passengers.

On the evening of 25 June, the prominent Social Democratic Party lawmaker Mizuho Fukushima was at the West Gate giving a speech about the government’s controversial labour reforms. It was the follow-up to a sequence of speeches and protests at the West Gate on 18 June, with protestors and opposition politicians appearing at stations and elsewhere to appeal to the public. (Fukushima also addressed a crowd that evening.) The so-called “work-style reform” legislation was eventually enacted by the Diet on 29 June.

25 June rally at Shinjuku Station West Gate (Nishiguchi) with Mizuho Fukushima. Image via @mkimpo_kid.

Launched by Mitsuko Uenishi, a law professor at Hosei University, Kokkai Public Viewing is a series of quasi-guerrilla actions that see large television screens temporarily installed in public spaces around Tokyo, showing the proceedings from the National Diet (Kokkai) related to important legislation — footage that is broadcast on television but rarely seen by people who work during the daytime. Since the first event in June at Shinbashi’s SL Plaza, the screenings have surfaced all over the city in recent weeks (one is planned for 12 August from 7pm to 8pm at Hachikō in Shibuya). On 23 July, Fukushima was again at the West Gate giving a speech and introducing Kokkai Public Viewing footage.

Similarly to the Saturday evening Shinjuku “standing demos” that are careful not to obstruct the foot traffic and, thus, avoid the need for a permit, these screenings can tactically, as de Certeau would put it, circumvent the legal constraints placed on more standard types of demonstrations and rallies. The organisers view their project as essentially open-source, inviting others to hold Kokkai Public Viewing using the guidelines on the website. They are much more than just outdoor screenings: they endeavour to re-democratise public space that often feels so commercial in Japan and divorced from the powers that run the nation.

23 July Kokkai Public Viewing event at Shinjuku Station West Gate with Mizuho Fukushima. Image via @mkimpo_kid

On 6 July, a decidely less stuffy or staid political rally was held in the evening at the West Gate with a Tanabata festival theme. Once again the main target of this “singing and dancing” demonstration was Prime Minister Abe and his cronyism scandal, though this time the participants dressed in yukata and colourful wigs, and used music rather than declamatory speeches. The movement is known as Michibata Kōgyō (literally, Roadside Industrial Enterprise) and emerged in early July out of a protest that took place outside the Kantei for several weeks from March. It continues to unfold regularly on the streets, including at the West Gate, and always with plenty of élan and charm. While the folk guerrillas are not exactly back in town, their successors are doing a fine job.

Michibata Kōgyō “singing and dancing” rally at Shinjuku Station West Gate on 6 July. Image via @mkimpo_kid.

Publicity image for another Michibata Kōgyō event on 8 August, held at Shinjuku Station West Gate outside the Odakyu Department Store, and raising money for people affected by the floods in western Japan earlier in the summer.

All this is not to suggest that Shinjuku Station West Gate has never hosted these kinds of practices in previous years, but the recent developments certainly represent a new energy — and one galvanised, if not even epitomised, by the Saturday evening protests. For all its concrete pillars and purported nomenclature as a passageway, the West Gate remains in spirit very much a plaza — and one of the most vital examples of one in a city where most of the large open space is privately owned or, even if public, hardly utilised.

WILLIAM ANDREWS

Excellent post.

LikeLike