As defined by Tokyo Photographic Art Museum curator Tasaka Hiroko, landscape theory (fūkeiron) was an engagement around 1970 with the ways in which “the structure of authority of the state and capital manifested as commonplace, everyday landscapes”.1 It involved an influential coterie of film-makers, photographers and critics in Japan in the late 1960s and early 1970s, most notably Matsuda Masao, Adachi Masao, Ōshima Nagisa, Hara Masato (Masataka) and Nakahira Takuma. Their collaborations and endeavours produced both a significant tranche of discourse (essays and articles, photography and text dialogues, round-table discussions, full-length books) and several key films, the most renowned of which are A.K.A. Serial Killer (1969) — a kind of “anti-film” or “anti-documentary” about spree killer Nagayama Norio comprising only the landscapes that he presumably saw during his peripatetic life until his arrest, narrated by a disembodied, dispassionate voice-over (in direct contrast to the sensationalized media coverage of Nagayama’s crimes) — and the Ōshima Nagisa cult classic Secret Story of the Post–Tokyo War: The Man Who Left His Will on Film (1970) (usually known in English just by its subtitle), about a man in search of the landscapes that a friend filmed before his suicide.

As noted by Hirasawa Gō, a film scholar and the foremost expert on landscape theory, this discourse emerged not only from the specific contexts of the Long Sixties, when the protest cycle was beginning to wane while Japan’s economic juggernaut continued to roar, but also from the nature travelogues and landscape writings by the likes of Shiga Shigetaka in the late nineteenth century.2 These ushered in a wide range of voices and thought on landscape, in particular what constituted the “Japanese” landscape, and such nationalist messages often dominated this discourse. We continue to live with the legacy of this Meiji iteration of landscape theory, as tourism campaigns and government efforts to promote Japan through soft power means almost always reach for lazy tropes of the country’s “pristine” and “beautiful” nature (often contrasted admiringly with the “high-tech” and “high-octane” buzz of “futuristic” Tokyo).

Matsuda’s new landscape theory circa 1970 was a response to this nationalist, romantic discourse, and its interrogation of the nation-state and post-war modernity is a defining feature of its achievements. Rather than a celebration of Japan’s incredible economic development, landscape theory problematized what this was doing to the regional character of the nation, and suggested that placeness was being usurped by the hidden presence of capitalism and the state. It was a political theory as much, if not far more, than an aesthetic one, and rooted in contemporary engagement with archipelagic concepts and practices, not to mention the activist-poet Tanigawa Gan’s critique of Tokyo during the 1960s.

As Matsuda famously wrote in his essay “City as Landscape” (1970):

[T]he unique local character was extremely eroded, and we discovered instead a homogenized landscape which can only be called a copy of the central city. Whether it was the colonized city Abashiri or the indigenous town of Itayanagi or ultimately the metropolitan city of Tokyo, they all looked almost identical to our eyes.3

The metropole subsumes all and the local is helpless in the face of the creeping, colonial force that invades the quotidian. We gaze at the landscape and it gazes back at us, surveilling inhabitant and visitor alike. The landscape rendered invisible the flows of exploitation and dispossession at a time when many people were migrating from regional parts of Japan to the large cities — leading to an emptying-out of the regions that remains chronic today — and attempts to capture the truth of Nagayama’s crimes via a camera failed, since the images contained only picturesque scenery. And it was at this landscape that, figuratively speaking, Nagayama fired his gun.

But beyond the binary of city/country, centre/periphery, beyond the violence of equivalence enacted upon the landscapes, we are urged to confront the homogeneity, to fight back: to engage with the landscape is to journey physically and geographically, to seek out our true selves hidden under the saturation of images, and to forge “livable purgatories” that purify our souls.

A.K.A. Serial Killer (1969) (dirs. Adachi Masao, Iwabuchi Susumu, Nonomura Masayuki, Yamazaki Yutaka, Sasaki Mamoru, Matsuda Masao)

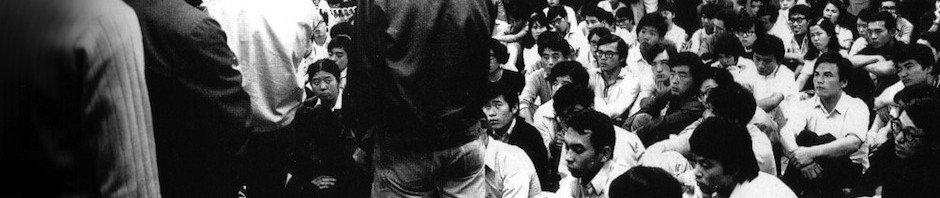

Landscape theory has undergone an extraordinary revival of interest this century, helped by the online availability of A.K.A. Serial Killer — a film so underground and obscure that it did not even receive a public screening until several years after completion — as well as the return of Adachi Masao to Japan after nearly three decades abroad, the efforts of Hirasawa and others to organize screenings and symposia in Japan and overseas, and a wealth of publications, not least a new, expanded edition of Matsuda’s landmark essay collection The Extinction of Landscape (1971) in 2013. Other scholars to contribute to this burgeoning field include Yuriko Furuhata, Rei Terada and Hayashi Michio.

Franz Prichard has delineated the remarkable interest in landscape theory, especially Matsuda’s work, as speaking

to the need to locate alterities within an expansion of the global imaginaries and aesthetic genealogies of the radical left. This has become an even more urgent task, in light of the ceaselessly destructive consolidations of neoliberal and state capital in the half-century since Matsuda’s essay “City as Landscape” (1970) first appeared.4

And so the opening of a new exhibition in Tokyo devoted entirely to landscape theory should be heralded as something of an apogee for this “landscape theory boom” ongoing since the early 2000s. On the other hand, it also marks the completion of an incredible trajectory of landscape theory that has taken it from a somewhat esoteric field, one that unfolded across obscure independent or underground films and a sprinkling of articles and texts published largely in specialist journals, to a movement that is feted at a public museum.

Aside from publications, the landscape theory revival has largely taken the form of screenings and events at festivals, universities, cinemas, film institutes and so on, raising awareness of previously obscure works and preparing the ground for reconsiderations of landscape theory’s importance. Exhibitions at art museums, though, have been relatively absent. A museum with an existing collection, not to mention several galleries for displaying different kinds of works and materials, can enable a different, perhaps more comprehensive approach that is apposite for a discourse that was transdisciplinary from the outset and engaged with preceding practices.

After the Landscape Theory runs at Tokyo Photographic Art Museum from 11 August to 5 November, 2023, curated by Tasaka Hiroko with the assistance of Hirasawa Gō. The exhibition attempts to present the landscape theory propounded by Matsuda, Adachi, Nakahira and others alongside subsequent practices. “What does it mean to engage with ‘landscape’ now, a half-century later?” as the opening text to the exhibition declares. The intent is to “reassess landscape theory, unravel various works of landscape-related expression, and explore the potential for new avenues”.5

The exhibition, which developed out of one about expanded cinema in Japan also curated by Tasaka (with Hirasawa and Julian Ross) in 2017, also includes an extensive screenings programme, with both works by the contemporary artists as well as of the earlier films highlighted among the exhibits (Boy, Secret Story of the Post–Tokyo War: The Man Who Left His Will on Film, A.K.A. Serial Killer, Red Army/PFLP: Declaration of World War), related works by Japanese film-makers like Group Posiposi, Nihon Documentarist Union and Takamine Gō, and other works by film-makers outside Japan in the 1970s like Jean-Luc Godard and Anne-Marie Miéville and Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet that adhere to aspects of landscape theory. It is one of the most impressive selections of landscape theory film works curated in Japan, though a minor quibble is the omission of a film like Eric Baudelaire’s Also Known As Jihadi (2017), made in direct response to A.K.A. Serial Killer and dealing with a radicalized migrant instead of Nagayama Norio.

The 4K restoration of A.K.A. Serial Killer, now in the collection of the museum, is also available to watch in the penultimate room of the exhibition, screening in full several times a day. It is worth the admission fee solely to watch this pioneering work in such crystal-clear quality, accentuating the picture-postcard beauty of the purported scenes from Nagayama’s life. For viewers with full knowledge of what Nagayama did, the effect is all the more chilling, and we find our eyes searching each image for meaning or explanation, for the clues hidden in the landscape — though, as Matsuda argues, the true clues have been rendered invisible by post-war modernity.

The exhibition also includes rooms containing works by more recent, quite divergent practitioners like Imai Norio, Sasaoka Keiko and Endō Maiko. The question that arises is: Does this somewhat patchwork approach yield dividends and further our understanding of landscape theory? While this does in part, the exhibition remains unsatisfying as a whole, primarily because, I would argue, of the parameters and internal logic it erects for itself.

I should preface all these claims with a caveat or disclaimer of sorts. I am an interested party here, a kind of fellow traveller. Though not a film scholar and not specifically concentrated on landscape theory, I have researched adjacent fields for some time, not least for a critical biography of Adachi Masao, whose early work forms the main focus of my current research. All this is to say that I have higher expectations and demands than a general visitor.

The exhibition is nominally arranged in reverse chronological order, starting in the 2000s–2020s, followed by 1970–2020, then 1968–1970, and only then reaching the “origins” of landscape theory, which includes exhibits from the late 1960s and early 1970s, most of which are short film clips and archival material in the form of journals and ephemera.

The title of the exhibition establishes a strong binary of landscape theory and post–landscape theory, and therein lies the rub. The exhibition fails to set up what landscape theory was besides an opening text on the panel near the entrance. The uninitiated are left to pick up the thread from this brief summary and then roll right into the first room — a somewhat crowded display of large prints from Sasaoka Keiko’s PARK CITY series of Hiroshima scenes — presumably with their eyes already filtering the exhibits as examples of post–landscape theory practices.

Positioning such a before-and-after binary based on a very specific theory/movement so centrally invites the viewer to interpret everything as in some way evincing signs of influence by or a response to the original practices. This, as will be discussed later, is not the explicit aim of the curator, but even attempting to do something more subtle is arguably neutered by not laying the groundwork from the start: namely, showing what landscape theory was and did, and the contexts from which it emerged (the waning student movement, the high-growth period, etc.).

Given that so much of the “original” landscape theory exhibits are rather dry archival displays, in which the visitor is forced to peer at the pages of journals or books in a glass case, or make guesses about a film’s content and style from just a short excerpt or poster, beginning with that room would certainly not make for the most inspiring start. Was that the reason behind the structure? Tasaka does not give an explicit rationale for the decision to place the exhibits in (almost) reverse chronological order, nor does the exhibition grapple with the problems that its choice of title conjures up.

This is not meant to appear churlish or pedantic over the wording of a title. The exhibition also omits to establish the more foundational landscape discourse — the true “original” landscape theory — that arose in the Meiji era, though it is referenced in the organizers’ greeting message to visitors. Given the overt way in which Matsuda and others were responding to that discourse, not to mention the resources available to the museum in its collection, would it not have made sense to begin there? And perhaps rather than the simplistic “before” and “after” suggested by the exhibition title, might it not have better reflected the discourse to frame landscape theory pluralistically, not as after “the” landscape theory, but everything as layers of landscape theory or as part of a continuum of landscape theories (or even just responses to landscape)? Within this, the efforts of Matsuda and his peers would have sat comfortably, as would have many other examples of photomedia and moving image.

These questions surface not least because the later practices showcased in the exhibition do not seem to resonate sharply enough with the works and materials presented as the “origins” of landscape theory. And that is to be expected, since Tasaka notes:

At first glance, while none of these works appear to have anything to do with the intersection of politics and art found in landscape theory, and though they differ from one another by era, by method, by technique and technology, and by philosophy, what you experience through all of the works is the imagination of the relatedness, historicity, and the whole range of issues contained within the details of commonplace landscape. In this, can’t we say they are a continuation of landscape theory?6

In other words, the exhibition treats landscape theory primarily as hinging on what is invisible in the landscape, and proffers various examples of subsequent practices that explore commonplace scenery. But to do so surrenders the ability to reassess landscape theory, as tantalizingly promised by the stated aims of the exhibition. And indeed, Tasaka performs a kind of volte-face in her curatorial essay in the catalogue by shifting the focus to the meaning of landscape itself, and the problematic nature of that very question. “By continuing to examine the invisibility that lies behind landscape and the history and memory that might once have existed there, it may become possible to come closer to an answer.”7 It is her right to do this, but I don’t think this was the key question that Matsuda’s landscape theory was originally asking, nor are the other post-Matsuda works in the exhibition rigorously engaged in that query in the way her essay suggests at the end. Landscape theory was a rupture with erstwhile accepted conventions of landscape. It is not enough to examine the invisibility behind landscape; the works must seek to problematize landscape itself.

The incongruity is possibly exasperated by the fact that various works exist that were directly related to or influenced by the original set of landscape theory works, aesthetically and conceptually, many of which are referenced by Hirasawa in his catalogue essay or included in the screenings programme. This genealogy is mostly absent from the exhibition rooms. The organizers’ greeting message proposes a more general and malleable definition of landscape theory: “the radical methodology of re-examining everyday landscapes from the angle of reality — expressing, through visual arts, landscape in its relationship to culture, society, and politics”.8 This has the potential to make all the exhibits feel consistent regardless of their theoretical, methodological or artistic correspondence, and yet the works ultimately never quite hang together.

In the exhibits dating from after the mid-1970s, landscape becomes a medium for personal, even confessional, meditation, not least Takashi Toshiko’s Itami series that is described as “a kind of diary” of her everyday life in Hyōgo, or it becomes an object of formal and media experimentation, as in Endō Maiko’s X, an online work that was originally uploaded daily during a festival and then re-edited for subsequent exhibition: the result is something visually interesting yet slight, a work that “was an experiment to see what could be conveyed to the viewer by faithfully relating the ‘naturally spontaneous’ movement of her own heart”.9

If landscape theory is just an artist playing with ways to capture images of landscapes through a lens, these become landscapes of affect, whereas Matsuda perceived landscapes of oppression. It might be tempting to posit the more confessional practices of the contemporary practitioners as symptomatic of Japanese art in late Shōwa, Heisei and Reiwa, which is often frequently yet inaccurately seen as apolitical and inward, even self-indulgent, as reflecting deeply entrenched anxieties and a wider societal shift away from political ideologies. (See, inter alia, art critic Matsui Midori’s concept of Micropop and Murakami Takashi’s Superflat.) These tropes have been exploited by certain artists and writers to great commercial success and it is not my intention to refute them entirely, but nor are they as applicable wholesale as is often presumed. Regardless, that analogy does not seem the intent here, and the same kind of highly personal approach is evident even in the 1970s work of Imai Norio, for instance.

The real danger, though, is that this co-opts landscape theory into a bourgeois ideal of the artist as someone producing greatness from their own subjectivity, when in fact the initial output of landscape theory possessed a strong anti-art and anti-auteur character. Even the very act of exhibiting all these works in an institution like a museum dedicated to photographic art inevitably reinforces that auteurism.

An aspect of landscape theory given less scope in the exhibition is its nature originally as a practice-led movement. When the film-makers shot A.K.A. Serial Killer, they traversed Japan, a long and arduous journey of detection in search of Nagayama, themselves and modern Japan. Likewise, when Wakamatsu Kōji and Adachi Masao travelled to the Middle East to film what became Red Army/PFLP: Declaration of World War (1971), it was an act of solidarity with the Palestinian cause, one enacted through physically going there, living among the guerrillas, and taking part in their everyday existence. Perhaps only Imai Norio’s exhibits come close to this, which integrate notes and a map, revealing the trail of images he took of the Abenosuji district of Osaka.

The other exhibits sometimes feel like false friends; works chosen from the museum collection because they match some of the tropes and motifs of landscape theory — namely, landscapes, the everyday, the invisible. But this risks diluting the original polemic of landscape theory or, in the less politically explicit practices like Nakahira’s, their aesthetic aggression and provocation. The crux lies not just in the everydayness of the landscape, but the tension between the everyday, the placeness, and external influences. The pieces from two series by Seino Yoshiko included in the exhibition portray intentionally anonymous landscapes; these locations could be Chiba, Aomori or Aichi. But this is framed as an enabling device of affect. Seino describes these anonymous landscapes as a “passage” that is opened to the viewer to apply to their life. Such works have a place in an exhibition about, say, landscape or the everyday, but these choices are (by the exhibition’s own admission) inconsistent with the politics of landscape theory and its engagement with power. As Adachi once said in 2008: “People say that power is located in the state as a mechanism of violence along with the military or police apparatus that guarantees that power, but this is only a small portion of power, a piece of the system. The point of landscape theory was to say that landscape itself is a reflection of the omnipresence of power.”10 When specificity is reduced to the anonymous, then the infrastructures and process of urbanization complicit in this act like an Althusserian ideological state apparatus, its tendrils spreading extensively and profusely.

Tasaka offers possible hints of new contexts that may be epistemologically and hermeneutically fertile. We live our lives today awash in images, furnished with the ability to take photographs and videos almost without thought, instantly, thanks to the phones we carry with us wherever we go. Our relationship with media is light years from the slower, methodically rigorous approaches that contemporary technologies forced Adachi and his collaborators to take while filming A.K.A. Serial Killer, though those very constraints contributed to the film’s aesthetic, which is essentially an example of slow cinema. Given our casual, almost unconscious relationship with the snapshot today, the aura of the landscape or picturesque is experienced in increasingly brief bursts. Might this suggest the time is ripe for a theory of landscape that is post-landscape? In other words, the exhibition’s gestures towards questions of contemporary lifestyle in an age of digital photomedia might have worked better if the whole exhibition was reconfigured to explore not landscape theory and what came after that discourse, but landscape in general and what is emerging after the concept of landscape has been challenged, rethought or even debased.

After the final room of the exhibition, which is taken up mostly with archival materials, the visitor must exit by circling back to the first space and leaving the way they came in. Happenstance of the floor layout though this may be, it does help to reframe Sasaoka’s PARK CITY in the light of the politicized landscape theory of Matsuda and his cohorts. Suddenly, we look at those images of Hiroshima through new eyes: of history and trauma diverted and, if not buried (since Sasaoka directly includes the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum), then in a state of repose beneath the everyday life of the residents decades after the atomic bombing. This effect is one of the best experiential moments of the exhibition and suggests a more side-by-side curatorial approach might have yielded fresher insights.

Given the issues with the selections of post–landscape theory works, we might assume that things would be on firmer ground with the “origins” of landscape theory section that forms the final part of the exhibition. With the exception of some Nakahira photographs and the room showing A.K.A. Serial Killer, the “conventional” landscape theory exhibits are mostly confined to archival materials like journal issues, books and posters. These are comprehensive, as anyone familiar with the discourse and paper trail of landscape theory will appreciate. Nonetheless, it is inherently difficult to exhibit discourse and visitors may tire of peering into glass cases to read the pages at which the publications are open. The section struggles to find a solution regarding how to exhibit a movement that primarily yielded films, which cannot all be shown in the same space, or published essays and photo series, which also cannot be displayed in archival form in full.

The section does include footage from films as examples of the “original” landscape theory, though the results are a mixed bag. Ōshima’s Boy (1969) is presented without explanation, not even in catalogue. Archival materials from the production (a press sheet, draft screenplay and still photographs) are included, and we are expected to fill in the blanks as to why it is supposed to demonstrate traits of landscape theory’s origins. The film portrays the titular young boy, whose family makes a living defrauding people, travelling from prefecture to prefecture to evade local police forces. Hirasawa, building on a suggestion by Sasaki Mamoru in 1970, has elsewhere elaborated on his assertion that Boy qualifies as part of the landscape theory canon.

They are arrested in Osaka, and all their bad deeds are revealed. What matters here, however, is not the characteristics and differences of the regions to which they escaped, or where they were caught. It is rather that the images of landscape depicted in the film indicate that everything, everywhere in Japan is subsumed by the state. This not only means that the entire land of Japan is controlled administratively from above by a repressive police governance. It rather means that all forms of power in everyday life are embedded as apparatus in landscape. This is evident in the images of the Japanese flag that are seen everywhere the family goes, regardless of whether metropolitan area or remote region. The family migrate silently in a landscape enclosed by such apparatuses. Despite the individual beauty of those landscapes, signs of violent interventions by the state are filmed in them. What is depicted here is the story of the family’s flight, but also the process of bringing the structures of state and power to the surface through the landscape they had to see in their daily lives. Whether they leave towns to escape the hands of the police, or slip into the crowd of the city, or even if they remain nearly inhumane as a family engaging in extortion, they cannot exist outside of Japan.11

The trailer from Secret Story of the Post–Tokyo War captures the oblique, cryptic nature of the film, but likewise does not demonstrate its relevance to landscape theory. Viewers may also find the excerpts and poster for Red Army/PFLP hard to parse. The footage of Wakamatsu’s Go, Go Second Time Virgin (1969) (written by Adachi) perhaps makes its pertinence clearer to viewers. The sexploitation film, part of an extraordinary cycle Wakamatsu-Adachi collaborations at the end of the 1960s and early 1970s, was critiqued by Matsuda in his landscape theory writings. However, Hirasawa’s suggestion in his catalogue essay that the Wakamatsu films Ecstasy of the Angels (1972) and Sex Jack (1970) (again written by Adachi) are also made in the “landscape theory mode” is not wholly convincing or expatiated.12 While the final shot of the bridge in Sex Jack was indeed described at the time as a metaphor for the Imperial Palace, and thus implying an attack on imperialism, such one-off moments do not seem to constitute real engagement with landscape theory.

Admirers of Nakahira’s work, of which there are many, may have wanted to see some of his slightly later work included, since it demonstrates more fully the scope of his interventions into landscape. As Franz Prichard has written in his recent monograph, Nakahira’s travels to Okinawa, Amami and Tokara between 1974 and 1978 were undertaken to “interrogate the role of photographic invisibility in the redrawing of the boundaries and pathways of the Japanese archipelago”.13

That process of redrawing boundaries and pathways has not ended and various practices are ongoing. There is no “pre” or “post” in this regard; everything is always “mid”. As my reservations about the current exhibition at the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum hopefully indicate, we are only just beginning to tap into the rich conceptual and aesthetic possibilities that landscape theory offers. May this work long continue.

WILLIAM ANDREWS

1. Tasaka Hiroko, “After the Landscape Theory”, trans. John Junkerman, in After the Landscape Theory, eds. Tasaka Hiroko, Hirasawa Gō and Kurokawa Noriyuki, exh. cat., Tokyo: Tokyo Photographic Art Museum, 2023, p. 12.

2. Hirasawa Gō, “Rethinking Landscape Theory: For the Sake of Post-Landscape Theory”, trans. John Junkerman, in After the Landscape Theory, p. 57.

3. Matsuda Masao, “Fūkei toshite no toshi” [City as Landscape] (1970), trans. Yūzō Sakuramoto, https://www.aub.edu.lb/art_galleries/Documents/Matsuda-City-as-Landscape.pdf.

4. Franz Prichard, “Introduction to ‘City as Landscape’ (1970) by Matsuda Masao (1933–2020)”, ARTMargins, 10, 1 (2021), p. 60.

5. After the Landscape Theory, p. 17.

6. Tasaka, p. 14.

7. Ibid., p. 15.

8. The Organizers, “Greetings”, trans. John Junkerman, in After the Landscape Theory, p. 5.

9. After the Landscape Theory, p. 26.

10. Harry Harootunian and Sabu Kohso, “Messages in a Bottle: An Interview with Filmmaker Masao Adachi”, trans. Philip Kaffen, boundary 2, 35, 3 (Fall 2008), p. 86.

11. Hirasawa Gō, “Landscape theory: post-68 revolutionary cinema in Japan”, PhD diss., Leiden University and Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3, 2021, p. 240.

12. Hirasawa Gō, “Rethinking Landscape Theory”, p. 62.

13. Franz Prichard, Residual Futures: The Urban Ecologies of Literary and Visual Media of 1960s and 1970s Japan, New York: Columbia University Press, 2019, p. 13.

References

Harootunian, Harry and Sabu Kohso, “Messages in a Bottle: An Interview with Filmmaker Masao Adachi”, trans. Philip Kaffen, boundary 2, 35, 3 (Fall 2008), 63–97.

Hirasawa Gō, “Landscape theory: post-68 revolutionary cinema in Japan”, PhD diss., Leiden University and Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3, 2021.

———, “Rethinking Landscape Theory: For the Sake of Post-Landscape Theory”, trans. John Junkerman, in After the Landscape Theory, eds. Tasaka Hiroko, Hirasawa Gō and Kurokawa Noriyuki, exh. cat., Tokyo: Tokyo Photographic Art Museum, 2023, 57–64.

Matsuda Masao, “Fūkei toshite no toshi” [City as Landscape] (1970), trans. Yūzō Sakuramoto, https://www.aub.edu.lb/art_galleries/Documents/Matsuda-City-as-Landscape.pdf.

The Organizers, “Greetings”, trans. John Junkerman, in After the Landscape Theory, 5.

Prichard, Franz, “Introduction to ‘City as Landscape’ (1970) by Matsuda Masao (1933–2020)”, ARTMargins, 10, 1 (2021), 60–66.

———, Residual Futures: The Urban Ecologies of Literary and Visual Media of 1960s and 1970s Japan, New York: Columbia University Press, 2019.

Tasaka Hiroko, “After the Landscape Theory”, trans. John Junkerman, in After the Landscape Theory, 12–16.

It is great to see this blog gets updated! And it is a great essay too.

It is normal to see any art movement gets its radicalized elements sanded down as it becomes more popular in the public consciousness. But when it comes to the Landscape theory, my question is whether that phenomenom was driven primarily by either:

– Commercialization. Is there anyone who became rich by doing Landscape art? Or any mainstream work of art that subscribed to the theory?

– The generational materialistic differences. It is not uncommon to hear Japanese born in the 40s and 50s saying things like: “I can’t recognize my childhood places anymore, because they have been encroached and swallowed up by the city.” But for people born in the 80s and 90s, that is the only world they know. There is no stark materialistic difference to make them instinctually ‘get’ Landscape theory.

LikeLike

Interesting stuff. Does any of this specifically engage with concrete – either as a material or as the expression of the Japanese economy, an effort to prop up the country through infrastructure spending as expressed by the pouring of concrete? (This article concerns the kind of thing I mean: https://www.theguardian.com/world/1999/jul/27/jonathanwatts)

LikeLike

@Chris M

In terms of engagement specifically with concrete or materials with a similar texture, there are interesting examples among recent photomedia practices focused on the post-2011 seawalls in Tohoku. Whether or not they count as landscape theory in the sense meant by Matsuda et al. is up for the debate, but then the exhibition at Tokyo Photographic Art Museum also, I felt, also seemed uncertain about how to deal with that same question.

LikeLike