When does a landscape die? What does a “dead” landscape look like? And can we see death in a seemingly benign, even beautiful, landscape? Posing these provocative questions, the photographer Sakata Haruto’s Sanrizuka series was first shown in August 2023 in an exhibition, Landscape of death (Eshi suru fūkei), at the artist-run space Totem Pole Photo Gallery. It deals with the contemporary landscape of a place synonymous with the fiercely opposed construction of Narita Airport.

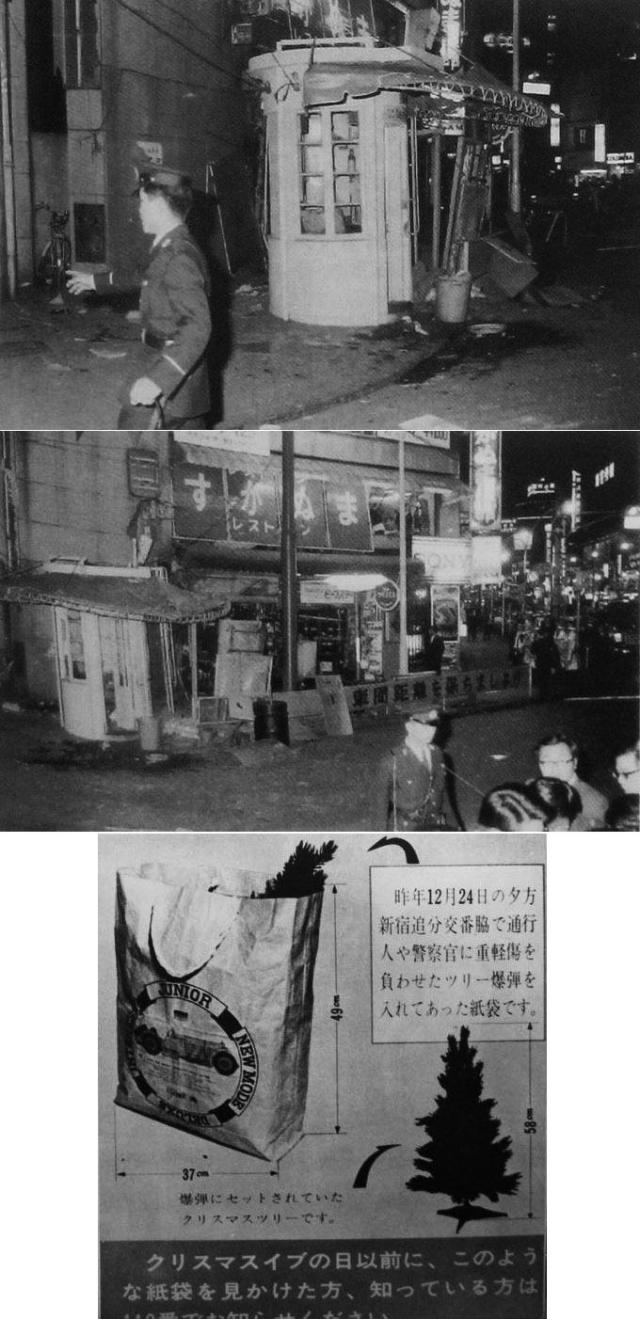

In the 1960s, the decision was taken to build a new international airport in a part of Chiba that was largely occupied by small agricultural villages, farmland, and a horse ranch owned by the Imperial Household Agency. The resulting land seizures were violently resisted by locals, supported by the New Left factions (then at the height of their influence), who framed the struggle not as NIMBYism but as part of the fight against the nation-state at a time when Okinawa remained occupied by the United States military and was central to the conflicts in Southeast Asia, and likewise other bases and facilities in Japan were vital cogs in the war machine. Completion of the airport was delayed by several years and, even after Narita did finally open, it did so at a greatly reduced scale than originally planned. The protests involved huge numbers in virtual pitched battles with the authorities at several key junctures (including as late as the 1980s) as well as longer-term campaigns that aimed to disrupt construction through direct action, including bombs. Four police officers died in clashes and two workers were killed in an arson attack (and a family member in an attack on the home of an aviation manufacturer), while at least two activists died. Several others died by suicide. The opposition movement eventually split acrimoniously. Today, a small yet fervent group continues to fight further expansion of the airport through rallies and lawsuits.

The title of Sakata’s exhibition derives from a 1970 book by the Nora-sha Collective and Kitai Kazuo, the photographer perhaps best known for images of Sanrizuka. Sakata is not directly referencing The Extinction of Landscape, the seminal collection of essays on landscape theory published by the film critic Matsuda Masao in 1971, but his project is clearly resonant with landscape theory.

Comprising a diverse set of photomedia and film practices as well as attendant discursive interventions in print media particularly at the end of the 1960s through the early 1970s, landscape theory sought to confront Japanese modernity, capitalism, power, and the discourse of the landscape and gaze. Scholars have identified numerous analogues in concurrent and subsequent practices worldwide, and artists continue to reference landscape theory in their work today, perhaps most notably Éric Baudelaire.

Sanrizuka was already the subject of a landscape theory practice in the early 1970s, the fifteen-minute 8 mm animation The Extinction of Landscape (1971) by Aihara Nobuhiro, which featured both scenes of construction of the airport and the protests as well as time-lapse photography of flora in the area. The Sanrizuka struggle was also the inspiration for several documentaries by Ogawa Shinsuke’s collective that are classics of militant cinema and practice-based nonfiction filmmaking, with the crew embedded among the farmers and wearing their bias so plainly that they suffered arrest for it.

Sakata’s work, though, stands in contrast with all this. He rejects the political subjectivity of Ogawa et al and the inherently political inflection of landscape theory in favour of a representation of landscape and the photographic gaze as neutral (or at least, what he avows to be neutral).

He professes no opposition to expansion of the airport in principle, albeit remains skeptical of the necessity for development given the climate crisis times in which we live. In this respect, Sakata does not approach Sanrizuka with baggage or bias: he became aware of the historical struggle against the airport only two years before he began exhibiting the series. As he writes in his first artist statement: “In search of distinctive satoyama landscapes, I set out to photograph the disappearing rural villages, but it was too late; depopulation had taken its toll. Village communities had collapsed and farmland lay in ruins. From what I could gather, most of the villagers seem to be in favor of the airport expansion. I’m not against the expansion, but in an era where environmental protection is paramount, it’s worth considering whether further intrusion into nature to construct massive man-made structures is justified. These landscapes, I believe, are a microcosm of our contemporary world, part of a much larger situation.”

In his statement for the second exhibition, he expands on this attitude. “I decided to adopt a neutral stance, focusing on observing the landscapes where the struggle took place. While the movement is still ongoing, I wanted to view it as a ‘struggle of the past’ from an objective perspective. Although Shinsuke Ogawa reportedly said that one should shoot from the farmers’ viewpoint and that neutrality is deceptive, I chose to pursue the middle path as an ideal, rather than the methodology of a ‘participatory film’.”

In concrete terms, this methodology comprises photography, field recording and video. Putting aside the latter two for the sake of expedience, can photography ever be truly neutral? Is there not always a stance, a bias, to some degree? Can we banish subjectivity entirely from the frame? Does orientation towards neutrality denote what Sontag called a flight from interpretation in its entirety? More importantly, perhaps especially for a subject like Sanrizuka, is this the right approach? Sans politics, what is left? A dry ethnographic record of the community? Merely the picturesque? Serenity? The rural idyll?

The second exhibition in the series, which was the first that I saw in person, seems to shift the focus to postmodernity. History of Metanarrative ran in December, again at Totem Pole Photo Gallery (of which Sakata is a member). The metanarrative, of course, is something that was supposed to end with postmodernist thought, giving way to localised and smaller narratives. Sanrizuka both exemplifies and contradicts this: it was a highly localised narrative that took on an intense, almost religious fervour over the defence of a place, and yet it was consistently framed in terms of grand narratives (the struggles against imperialism, against the nation-state, against capitalism, inter alia).

Postmodernity’s skepticism towards metanarratives should not conflated with disillusionment and apathy, the latter frequently cited as a characteristic of the generations in Japan that came of age in and since the Heisei period. It has been convenient framing: with the economy in the doldrums, there was far less optimism going around, and this seemed to dovetail with the general decline in voter turnout, the birth rate decline, the increasing numbers of shut-ins and dropouts, the atomization of mass culture with the arrival of the internet, and so on. Born in 2000, Sakata is a dyed-in-the-wool member of this cohort, who encounter no politics on their university campuses (occasional flare-ups like SEALDs in the mid-2010s notwithstanding) and enter an uncertain job market upon graduation. Should we read Sakata’s rejection of a political stance for his practice in line with a postmodern or post-Shōwa paradigm?

“What does it mean to see the grand narratives of the past through landscapes?” he asks in the artist statement. “The students who fervently believed in revolution. The farmers who dreamed of a new liberated zone, a utopia, when the airport construction was halted. The people who hoped for the growth of the nation thanks to the airport. As grand narratives are becoming prominent again, could we perhaps derive new ideas by observing the structures of past ideological conflicts through these landscapes?”

If you are professing neutrality, any answer to that first question becomes a moot point because you, the practitioner, are nominally not seeing the metanarratives of the past in the landscape, or are seeking to avoid framing them that way for the viewer. And yet Sakata does seem aware of the bigger societal shifts — Black Lives Matter, MeToo, climate activism, to name a few — and that these affect any attempt to look again at historical movements, even if just by osmosis.

The exhibition featured a select number of images in large-format prints pinned to the walls. These showed signs of life and habitation, but no signs of activity (which is a crucial distinction to make). Instead, the viewer beheld fields and forests, roads and infrastructure. The images felt flat, bereft of human figures to put them in scale, so to speak. A parking lot has highway coaches, but no passengers. A playground sits eerily empty (a sign as much of depopulation and birth rate decline as the oppressive development of the airport). What seems to be a church is an incongruous sight in a Japanese pastoral scene, but makes sense to anyone who knows about the late Tomura Issaku, the original leader of the protest movement. The only apparent sign of life is a train passing over raised tracks above a field, though this felt impersonal and almost vertically imposed upon the landscape. (It is presumably the Shibayama Line, a rarely used line built as compensation for the separation of communications in the area, cleft in two by the airport.) In this way, the viewer searched for clues, and found little concrete. The well-versed viewer would recognise more, but was still frustrated by the vacant, uncaptioned images.

The absence of human life complicates the ethnographic, documentarian nature of the series, and also, conversely, makes the images more like landscapes (in defiance of the death of landscape referenced in the exhibition titles). Perhaps, then, we should regard Sakata’s nonhuman or human-less mode of representation as an attempt to decenter the ethnographic record of a place and foreground only the locations themselves, sans inhabitants. Sakamoto Hirofumi draws a parallel between Aihara Nobuhiro’s focus on flora and abandoned houses and Nakahira Takuma’s rejection of a human-centric view of the world in favour of an “illustrated botanical dictionary” in 1973. Of relevance here may be film scholar Laura Rascaroli’s notion of the ethnolandscape: “landscape as the product of a specific gaze, stemming from a number of traditions and discourses that combine art, science, and popular entertainment, spectacle, power, and ideology.” In other words, you can take the people out of the landscape, but you can’t separate the landscape from the traces of the people who were there, whose presence and gazes are what made the landscape in the first place. (Cf. Simmel and his interpretation of landscape as a creative achievement, seen and made anew by the artist, while the general viewer relates to a landscape, both in nature and in art, through the “wholeness of the being of nature” that draws us in.)

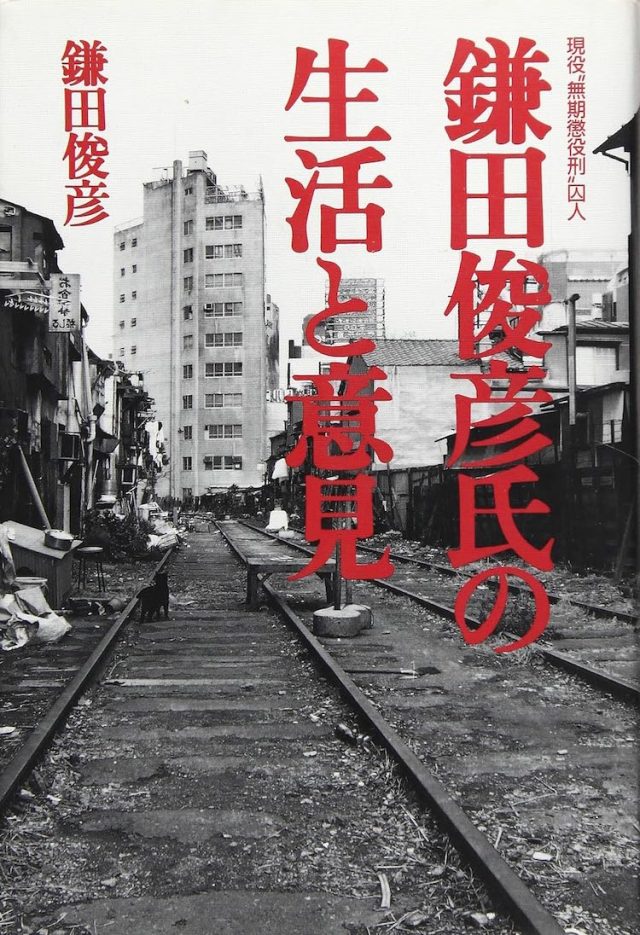

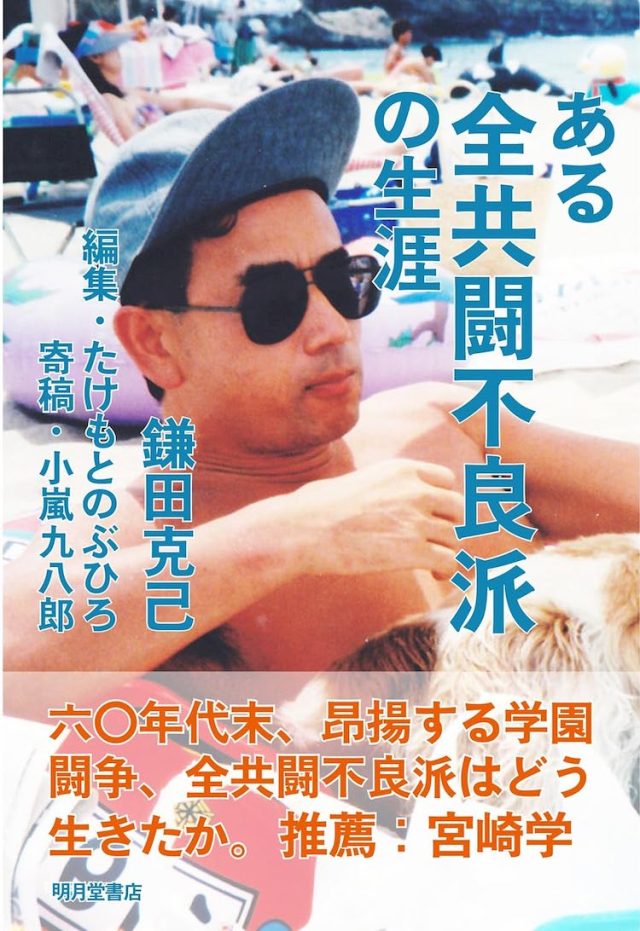

You may note that I am pointedly avoiding a certain conceptual buzzword — hauntology — despite the obvious temptation to apply it here, since to do so would open up a whole new can of epistemological worms. The venue was, however, if not haunted then at least attended by traces of the past. A pile of memoirs and other books stood by the doorway to the gallery. A table in the middle of the space likewise hosted a pool of primary sources (media coverage, etc., photojournalism of 1970s land resistance). The magazines were pointedly open to these pages, deliberately contrasting with the plain, contemporary images on the surrounding walls. This, whether Sakata wanted it or not, generated a before-and-after effect (and indeed, the affect of before-and-after). And the conscious choice to bring research materials, especially primary materials written by first-hand observers and participants, was an attempt to lend not only context but also authenticity and authority to the present-day images. (This marked a development from the first exhibition, which limited the resources available in the middle of the room to the Nora-sha Collective and Kitai Kazuo book and another publication, and a map with the locations of each photograph.) The photographs on the walls and the resources on the table became reciprocally indexical: that is, they bestowed contexts on each other; this became that, that was once like this. Neutrality went out the window, whatever the artist statement said.

Held at Totem Pole Photo Gallery in January and February this year, the third exhibition in the series was the second to bear the (slightly rejigged in English) title of Death of Landscape, came with the subtitle Landscape Variations.

Due to an infection, I was masked during my visit, which felt oddly appropriate, as if I were an activist from past arriving at a rally incognito to hide my identity from police photographers. The truth was far more prosaic, of course, yet the work on display likewise played with mundanity and spectacle, and the blurry world in between.

The “non-politics” of the series was more problematized in this iteration, which tackled less the past than the present and future of Sanrizuka, facing further encroachment, if not outright extinction, by the proposed expansion of the airport. From the artist statement: “This area is famous for its vehement protests against the airport’s construction, inspiring a myriad of movies, photo books, plays and artworks, thus becoming a sort of holy ground for protest art. Back then, recording and photographing by protesters was commonplace. However, rather than creating directly within this context, I opted to deliberately leave out human subjects in my photography. By coldly observing and methodically documenting the landscape, I sought to maintain a neutral stance, moving beyond superficial humanism.”

This begs the riposte, is neutrality not the more superficial form of humanism? Moreover, it became increasingly clear that the claimed neutrality of the stance and aesthetic actually conjures affect. The viewer asks what is not present and why. The viewer questions the origin and impact of roads. They worry about the crops. Without the context of Sanrizuka, it would be another matter entirely, but the “cold” observational style cannot help but appear deliberate — and, moreover, suggestive. The images become, in short, sympathetic to Sanrizuka because they are presented to us within a specific set of circumstances. And considering the careful efforts Sakata goes to with his artist statements (which are bilingual, to boot) and other reference materials provided in the venue, he is complicit in this act of context-layering of the images in advance.

The gesture towards neutrality and the landscape is not a flight from interpretation, but an expression of a certain interpretation in its own right: a decision to interpret Sanrizuka without explicit triggers of punctum, as a stripped-down aesthetic, and to banish the studium outside the frame to accompanying reference materials and artist statements in the venue. And yet this bare aesthetic provokes an emotional response by its very unembellished and unspectacular nature: the viewer fills in the blanks, sees the context behind the present-day landscape.

The third exhibition was notably more comprehensive, featuring a larger number of prints (in pinned sheets of twenty small images, in deliberately random layouts). These showed a greater range of landscapes, from fields to farms, fences, roads, cemetery, planes and forest shrines. There was also more infrastructure and presumed activity. While no human figures were shown overtly, neither were the images bereft of life. Indeed, these landscapes were curiously more populated than before: diggers seem only temporarily abandoned, a bonfire burns, a kei truck is parked with a portaloo on the bed, etc. A car driving along a country road must surely contain a driver. Squint and you could actually see a farmer in a plough vehicle in a paddy. The people were camouflaged, not absent.

The scenery of satoyama — a common, even hackneyed Japanese cultural trope of agriculture and countryside in harmony — is disrupted by the airport, for sure, but there are other signs of disquiet too. A small road is sandwiched between a pair of fences endlessly stretching out; an enclave enclosed by the airport. There was more emphasis on the planes in the sky overhead, which felt ominous despite the azure (like with the previous exhibition, all shots were taken on bright days and even the dull concrete and asphalt looked pellucid). And yet, this was not a simplistic image of man versus nature, of Arcadia disturbed, since the farms themselves use modern tractors. The concrete and asphalt has encroached into the pastoral much more pervasively than just the obvious violence of the airport itself. And is nature winning? Do we not see signs of rewilding? A watchtower in one image is overgrown with foliage and the surrounding fences rusting, no longer used with the decline of the protest movements. Nature’s return to the fore is concomitant with the ebbing of radical politics.

This third iteration of the series included a film projection of an annual sumo tournament at a shrine that faces destruction with the airport expansion (this is the only explicit sign of human activity in the series and it seems significant that the medium chosen for it is moving image, not still photography). Almost everything shown in the gallery, we realise, will disappear. This imbued the exhibition with a more obviously elegiac tone than previous entries. In part, this was due to the footage of the sumo bouts. The implied loss made the footage wistful and raw.

Ultimately, the viewer left with the impression not so much of a “death” of landscape; rather, of an altered and, perhaps begrudgingly, tolerating landscape.

Sakata’s series will next be shown at Bar Jūgatsu in Golden Gai, from March 16 to March 30. The bar is named after the owner’s birth month, but apparently many assume the moniker is a nod to the Bolshevik revolution. This ambiguity perhaps makes it a particularly apt venue for the series.

WILLIAM ANDREWS

All images from Sakata Haruto’s Death of landscape (2023).