In December last year Susumu Hagiwara passed away at the age of 69. He had been one of the most senior figures in the remaining Narita protest movement, which even if people have heard of it — and many Japanese people surprisingly haven’t — they would probably never imagine that it still continues to this day.

The visitor to Tokyo invariably enters the city via Narita International Airport, an experience likely to leave them struck by the unspectacular mediocrity of the biggest airport of the world’s third biggest economy. In 2020, how many of the visitors to the Olympics will ponder the same thing? No Heathrow or JFK this one. Narita is an odd, anti-climatic patch of concrete out in the green fields of Chiba Prefecture, east of Tokyo. Express train routes and coach services zip passengers out of this curiously small hub — yes, there really is more than one terminal, despite how itsy the whole place feels — and these conveniences today make the distance between the airport and the city centre much easier to bear, but it still seems isolated. Even the arrivals gate is stunted, like it wants to be a portal for emotional reunions but instead gets dwarfed by any of the many ticket gates at a major Tokyo train station. As you leave and begin somehow to eat away at the nearly 60km until you reach civilisation, you can have time to reflect on just how much land there is between Narita and Tokyo. And there was once even more, since before Narita was constructed, the site was agricultural.

In the 1960’s the decision was made to build a new international airport to support the needs of a Japan that was buoyant and bulging. The Tokyo Olympic Games had been held in 1964. The bullet train was running. Incomes were rapidly increasing for much of the population. Haneda was not enough. Japan needed a juggernaut of an airport to prop up its hubris in the age of massive economic advancement. It was to be the largest public works project in Japanese history and the most contested, though the final construction was ultimately only a third of the size of the original master plan and even this was painfully delayed.

The final site chosen lay over farming land in Chiba Prefecture. Despite the name, the airport is not in Narita. That is a small city nearby. The actual airport occupies several agricultural areas, the most famous of which was to become the symbol of the protest movement that continues even today to resist the airport. This was Sanrizuka.

Not everyone affected was a small landholder, though. In fact, the biggest share of the land belonged to the Imperial Household, who owned a pasture in the area. It was ceremonially handed over to the state so that the nation could have its juggernaut. The airport was to be another success story in Japan’s remarkable narrative of post-war reconstruction, which saw the country layer its cities with infrastructure, burrow tunnels through its mountains, and dam almost all its rivers. (Not for nothing the writer Alex Kerr once called Japan the “world’s ugliest country”.) But in its haste, the state overlooked the tenacity of the spurned farmers, who they assumed they could buy off without consulting before announcing the site. The farmers were mortified, as were local officials, who had likewise been sidelined by the state authorities. What erupted next was a gestated, bitter decade-long campaign to stop the airport being built.

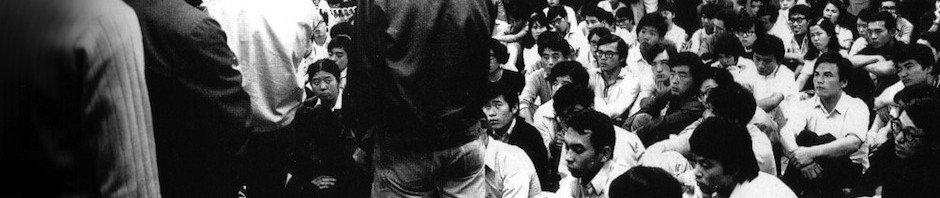

The farmers joined together and engaged in legal obfuscations to stop the forcible purchase of land. But what really made an impact was how these motley country bumpkins were prepared to fight physically if needs be, and they were not alone. Sanrizuka became a cause célèbre that attracted the support of the student movement, then at its peak in Japan, and other New Left radical groups.

Hantai Dōmei, or Sanrizuka-Shibayama United Opposition League Against the Construction of Narita Airport, built ditches, chained themselves to trees and launched shit from catapults. They built forts and bunkers. This was all-out insurrection. The mainstream leftist political parties fled when the protests turned violent but the ferocity of the struggle only added to the necessity for New Left troops to make the journey from Tokyo to Chiba. Student activists and other radicals from groups like Chūkaku (Central Core Faction), a hardcore militant organisation at the time, reinforced the forts marking and protecting the farmers’ land from the encroachment of the airport. The state’s campaign to seize the Sanrizuka fields was seen by the New Left in the same context as the other major struggles at the time: the continued presence of US bases in Japan and the terms of the restoration of Okinawan sovereignty to Japan; the Vietnam War and America’s use of Japanese bases to fuel the war machine; and in the 1980’s, the New Liberalist ideology that saw the LDP government also break up the unions and privatise the national railway.

Twenty-four hour watches were kept at the towers and huts the students and farmers built. Far from being weekend protestors, the activists committed themselves to the Sanrizuka and many moved there full-time. Some farmers even ended up marrying the outsiders.

The first land survey was conducted on October 10th, 1967, supported by 2,000 riot police. Hantai Dōmei blocked the roads and the protests turned violent. Issaku Tomura, the Christian leader of Hantai Dōmei, was beaten to the ground by police and a bloodied picture of the middle-aged man further turned people against the airport project. The later land surveys in 1968 met impassioned protests, while the first and second land expropriations in February and September 1971 have become notorious. The police deployed 5,000 officers with water cannons, cranes and more in the second operation, only to be met with such aggression on the side of the protestors that three riot police were killed in one clash.

One student hanged himself in despair at what was happening. Another student was hit by a gas shell and killed in 1977 when the authorities moved to dismantle the protestors’ iconic steel tower used to broadcast slogans. Overall, four police lost their lives during the course of the protest movement; thousands of protestors were arrested and injured. And the airport was still not ready.

When the full resources of a nation is set on doing something, you cannot stop it unless you have an army. The protestors were belligerent, often paramilitary, but they were no match in the end for the state. Narita, Japan’s white elephant, did eventually open in 1978, 1,600 hectares in size and with a 4,000-metre runway, though even at this late juncture there was a final stunt. In March, the gleaming, ready-to-open site was stormed by hundreds of radicals. A burning truck rammed and burst into a gate. (One of the drivers would later die from burns.) But this was all a distraction so the security would concentrate on the main attackers, leaving a band of saboteurs to infiltrate the control tower. They then caused carnage to the equipment as they occupied the tower, barricading themselves in for hours. This led to two more months of delay while the damage was repaired. And yet, inevitably, the airport still opened and the planes began to come.

But as anyone with experience of protest movements in Japan knows, Japanese protestors never give up. When the government announced plans to build a new runway, gradually building more of its original master plan, Chūkaku-ha and the farmers launched a new campaign, which led to violent clashes with police in the 1980’s. The second runway and terminal was, nonetheless, completed.

And yet Narita never became the Asian hub it was supposed to be, mostly due to its expensive landing fees, which far exceed those at Seoul’s or Hong Kong’s airports. Haneda, which is laudably close to Tokyo in the west, now also runs international long haul flights again, though Narita is not to be outgunned. Its annual takeoffs and landings are rising, and it still harbors hopes for a third runway, which would finally complete the original vision for this most controversial of airports. These dreams are indefinitely on hold, it seems, but with demographics weighted in the authorities’ favor, it is perhaps only a matter of time before the remaining obstacles are quite literally gone.

Sanrizuka is nearly forgotten, though the place itself still exists on the outskirts of the airport. I have mentioned its name to Japanese people under forty and frequently they have never heard of it, and sometimes are not even aware of the airport protest movement at all. A worthy museum about the airport has opened in the past few years and it commendably does not shy away from including a lot of exhibits and information on the protest movement. However, this very act is a confirmation of the movement’s denouement. It is now caught up in the process of being memorialised. The huts and “fortresses” once occupied twenty-four-seven by protestors have been pulled down. The coda is not yet written; rallies and demos are still held regularly by farmers and New Left groups. The authorities continue to take these seriously and the police presence is high, despite the far smaller numbers of participants than in yesteryears. The original farmers are dying off and the “protestors”, while not without some hardcore youthful political activists from Zengakuren, are mostly elderly. Hagiwara was a relatively young 69 when he died last year. Kōji Kitahara is much older and quite frail these days. He remains the leader of the surviving protest movement, which is active today in spite of a split in 1983 between those who would accept the terms of the authorities and who vowed to fight on.

They have another challenge on the horizon. The next chapter in the Narita saga is likely to be the LCC terminal being constructed now, expected to be ready in 2015 for visitors to take advantage of cheaper air travel to Tokyo. But not so much the airport’s infamous landing fees, the real reason Narita will never be “low-cost” is that it has already paid such a high price in the anguish and struggle to be built in the first place.

WILLIAM ANDREWS

Further reading in English:

Apter, David E. and Nagayo Sawa, Against the State: Politics and Social Protest in Japan, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984.

This is without a doubt one of the strangest protests in human history. Communists, who would have nationalized ALL the land in Japan, joined farmers in protesting the nationalization of some of the land. Communists, whose ideology calls for the mobilization of “each according to his means”, joined with farmers in protesting modernity. I have read much about this in Japanese and never once seen an explanation that satisfies me.

LikeLike

@Avery

This is quite complicated because there were just so many groups trying to claim their piece of the Sanrizuka pie. Agrarian radicalism in Japan, with some exceptions, was often conservative in nature, so the anti-Narita Airport movement was quite transcendental in this respect in that it linked NIMBY-ist farmers with far-left student and worker factions.

The Old Left groups were also involved a little at the start but then scuttled off when the riot police turned up. Above all, we have to keep in mind the timing — Narita was announced during the Vietnam War and in the lead-up to the renewal of the Anpo treaty in 1970. The airport became a symbol of Japanese complicity with America in the war (since people feared the airport might be used by American airplanes or at least to send Japanese supplies to bases). The issue was how the land was to be used — as a triumphant platform for capitalism (trade, commerce, tourism) and realpolitik. Narita was treated as a de facto military base and the ferocity of the protests ironically did almost effectively transform it into one, with thousands of riot police stationed there at one point. Security and surveillance around the grounds remains high.

Okinawa, like Narita, was a convenient unifying cause in the 1960’s and 1970’s. The fact that there were many fractures and internal conflicts confirms, though, how shaky some of the common ground was. That said, for the first several years it was still a formidable and united opposition movement.

The protest movement is still going, with a demo scheduled for later this month. It remains supported by Chūkaku-ha and Kaihō-ha.

I recommend the Apter/Sawa text. It was researched and written over twenty years ago and the second runway conflict kicked off after its publication, but it goes into a lot of detail about the living conditions of the various factions and protestors camped out around the airport site.

Anyway, I hope to write more about Narita soon.

LikeLike

I didn’t see this reply until just now — but thank you for expanding on this at length, and for the book recommendation! It still seems to me like this was at its heart an anti-modern protest, with the ominous presence of airplanes being some kind of symbol for Vietnam, the Cold War, and foreign things arriving in Japan. Looking forward to your future posts.

LikeLike

It’s because communism is for people who are idiots.

LikeLike

idiots are people who dont understand what communism is.

LikeLike

Thank you for this. Quick question. Was Itami the primary international hub before Narita became operational?

LikeLike

@Jason Gregg

It was Haneda.

LikeLike

Absolutely fascinating, thank you for sharing this.

LikeLike