Any attempt to learn about the New Left or student movement in Japan immediately runs into trouble unless you can get your head around the complex skein of factions and their various genealogical branches. One major “family” in the pantheon of the Japanese New Left stems from Kakukyōdō.

While the Kyōsandō (Communist League) — popularly known by the mock-German name Bunto (Bund) — was formed in 1958 by radical members breaking away from the ossified Japanese Communist Party, Kakukyōdō had already been established separately in 1957 as a wholly alternative organisation to the JCP. Together, the creation of the two leagues is generally seen as the birth of the New Left in Japan.

Originally known as the Japanese Trotskyist League, it would in time shift from Trotskyism to a more back-to-basics Leninist ideology summed up by its key slogan of a “proletarian world revolution, against imperialism and Stalinism”. The name change happened almost straightaway. After being founded in January 1957 by a small group including Kanichi Kuroda, Ryū Ōta and Osamu Saikyō, in December of the same year it was rechristened the Kakumeiteki Kyōsanshugisha Dōmei (Revolutionary Communist League). Taking the first characters from the three parts of its name, it is usually called Kakukyōdō, often pronounced Kakkyōdō.

However, leftist factions are prone to split and mutate, and this was the case with Kakukyōdō from the start.

First Split

An internal schism took place in July 1958 over ideological issues of Trotskyism and criticism of the Soviet Union. Ryū Ōta left Kakukyōdō to form a separate Trotskyist group and work closer with the Socialist Party.

Second Split

A more serious fracture occurred in 1959, when Kuroda was denounced as a JCP and police spy. Kuroda was leading the push for the group’s ideological stance to be more anti-Stalinist. Kuroda was thrown out in August and he left with his own faction, including Nobuyoshi Honda, to form a new Kakukyōdō. This is formally known as the Kakumeiteki Kyōsanshugisha Dōmei Zenkoku Iinkai (Revolutionary Communist League – National Committee), though like almost all the various versions and incarnations it is also popularly called Kakukyōdō.

Third Split

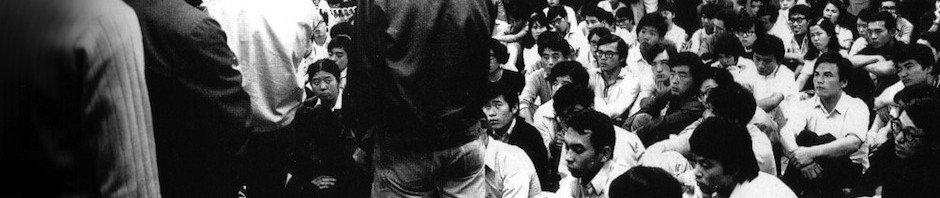

Kuroda and Honda’s Kakukyōdō emerged as a dominant player in the New Left scene in Japan during the 1960 Anpo campaign and, as the Bund’s Zengakuren (student council league) group collapsed, assumed the main Zengakuren mantle through its student arm, Marugakudō. However, then came a definitive and extremely painful rift in 1962 during the Third National Committee meeting. Deciding on concrete strategies for moving forward with the revolutionary struggle, division appeared in Kakukyōdō over issues to do with the formation of regional committees for a militant labour movement.

The end result was that in 1963 Kuroda broke away with a large contingent. This new Kakukyōdō was the Nihon Kakumeiteki Kyōsanshugisha Dōmei Kakumeiteki Marukusushugi-ha (Japan Revolutionary Communist League Revolutionary Marxist Faction), though it is almost always referred to by its nickname, Kakumaru-ha. It founded a new organ paper, Kaihō (Liberation), and based itself in the Waseda area of Tokyo, near to its stronghold of Waseda University. Its student activists would wear white helmets with a red line around the bottom and a large black “Z”.

Marugakudō was also split when its parent divorced. Kakumaru-ha would initially be dominant in the student movement, since Kuroda has a strong following among the young.

What was left of the Kakukyōdō National Committee became known as the Chūkaku-ha (Central Core Faction). This was more precisely the colloquial name for its student wing. However, not least because during the 1960s Kakukyōdō was essentially seen fundamentally as a student activists’ group, “Chūkaku” became accepted effectively as a name for the whole league, in particular in opposition to the other -ha, Kakumaru. Today members themselves tend to use the name Kakukyōdō, though.

The Chūkaku organ continued to be Zenshin (Forward March), the Kakukyōdō newspaper since 1959, and it was initially based near Ikebukuro, though later moved to its current home in Edogawa. Chūkaku-ha’s stronghold in Tokyo was Hōsei University. The Chūkaku-ha helmet was white with the two characters for “Chūkaku” written in black.

The Kakumaru-ha and Chūkaku-ha split was made more chronic during the campus strikes in Japan, especially the famous occupation of Yasuda Hall by students at the end of the University of Tokyo Zenkyōtō student movement (1968-69). The Kakumaru-ha contingent left their posts just prior to the final stand against the riot police in January 1969, since they believed the struggle to be futile (accurately enough, as it turned out). This pragmatism lies in Kakumaru-ha’s general emphasis on the survival of the overall party above the goals of an individual campaign. Chūkaku-ha saw the Yasuda withdrawal as a betrayal and it sparked off a violent war between the two factions (with others also involved), with scores murdered over the next decade. Chūkaku-ha’s leader Nobuyoshi Honda himself would be the most high-profile victim, killed in his apartment in 1975.

As both sides have moved away from their focus on the student movement to become primarily labour groups, the privatisation of the National Railways in Japan also created bitter ammunition for the rivals, with Chūkaku accusing Kakumaru-ha-affiliated railway unionists of “colluding” with the breakup and formation of JR in the 1980s.

Fourth International Japan

In 1965, those like Osamu Saikyō who had remained in the original Kakukyōdō (often called the “West Faction” or “Kansai Faction”) in 1959 now joined up with Ryū Ōta’s International Communist Party to form Fourth International Japan (Daiyon Intānashonaru Nihon Shibu), and were given formal recognition by the Fourth International headquarters. Like its peers, it also called itself Nihon Kakumeiteki Kyōsanshugisha Dōmei (Japan Revolutionary Communist League), and was known colloquially as Daiyon Intā or sometimes (more abusively) Yontoro.

Critical of the leftist infighting (uchi-geba) so consuming other factions, Fourth International Japan would be an instrumental participant in the New Left crusades in the late 1960s and 1970s, especially the campaign at Sanrizuka against the construction of Narita International Airport. Its organ was Sekai Kakumei (World Revolution) and activists wore red helmets with hammer and sickle insignia. Its student base was strongest at several regional universities and at Sophia University in Tokyo.

Fourth International Japan Split

Fourth International Japan had run into trouble almost as soon as it was founded in 1965 when Ōta left (he would change trajectory several times in his long career, including as Ainu separatist, environmentalist and conspiracy theorist). It then began to split in the late 1980s, with some breakaway groups leaving the fold after a rape scandal. It reformed and renamed in 1991 as (and here’s a familiar name) Nihon Kakumeiteki Kyōsanshugisha Dōmei, the Japan Revolutionary Communist League (JRCL), with a weekly organ, Kakehashi (Bridge, Intermediary). Since then it has offered public self-criticism of sexual discrimination, a previously chronic issue in the New Left in Japan. Though it maintains links with the wider Fourth International movement, it is no longer the “Japan branch”.

Chūkaku-ha Kansai Split (Fourth Split)

Rumblings of trouble in Kansai began in 2006. The so-called Party Revolution took place in 2006, with two factions in Kansai ultimately expelled or leaving. The Yoda-ha faction had long opposed the May Theses of 1991, which marked an ideological shift in Chūkaku-ha from fighting Kakumaru-ha and the Japanese imperial state to an emphasis on the organising of labour in the workplace. The faction was pushed out in March 2006 and then in autumn 2007, the Shiokawa-ha (Shiokawa Faction) in Kansai also left following opposition to the July Theses announced that year.

Shiokawa’s group had similar misgivings as Yoda’s but the new split also emerged out of conflict over attitudes towards ethnic minorities. (Kansai has the largest proportion of Korean Japanese in the country, as well as a high population of Buraku former lower caste.) In the past Chūkaku-ha has had a problematic relationship with immigrant and minority rights activists and while it has worked hard to form alliances more recently, issues between the groups still crop up periodically. The Shiokawa-ha were criticised as denunciatory subscribers to a “blood debt” (in Chūkaku-ha terminology this is called kessaishugi).

The “revolution” marked a complete transformation into a workers’ party, though it meant the league lost around ten per cent of its membership. The remainders of Chūkaku-ha are now sometimes known as the Chūō-ha (Central Faction) or Zenshin-ha. A positive is that it led to Chūkaku-ha finally formulating its ideology into a draft program, surprisingly for the first time. (Kakumaru-ha has always been much more adept at such formal theorising, especially as it originally had a philosopher figure as its leader.)

The Shiokawa group set up the Kakumeiteki Kyōsanshugisha Dōmei Saiken Kyōgikai, the Revolutionary Communist League Reconstruction Council. Its main organ is Mirai (The Future). Kakukyōdō Chūkaku-ha accordingly created a new Kansai region committee in late 2007, though its strength in western and southern Japan was weakened by the split.

So how many “Revolutionary Communist Leagues” are there? Ultimately, due to the acrimonious nature of the schisms over the years, the rights to the ownership of the name Kakukyōdō depends very much on the claimant.

WILLIAM ANDREWS