If we ignore all the labyrinthine offshoots — the extra stations, the spirals of connecting underground arcades — Shinjuku Station is surprisingly simple: two main gates, one on the east leading into the major commercial district, and the other on the west, opening onto several large electronics stores and hotels, with flashes of architecture looming large overhead, including two attractions by Tange Associates, the Mode Gakuen Cocoon Tower and the Tokyo Metropolitan Government Building complex.

In between these exit gates run two concourses deep inside the JR station subterranean bunker. The West Exit’s gates don’t send you straight out into the noise of Bic Camera et al. First you have pass through an underground space, curving around two ramps for taxis and buses, that funnels you up to street level through various corridors, stairways or doors. Immediately above you is the Odakyu Department Store and then a field of asphalt filled with bus stops (take a wrong staircase and you may end up marooned on a bus stop island). It is always a bustling bottleneck, all the arteries thronging with people on their way somewhere. No one ever seems to stop or loiter, perhaps just to pause at a kiosk and make a purchase, before continuing on one’s way to that all-important final destination. It is a site existing apparently only for the act of transit onward to another place.

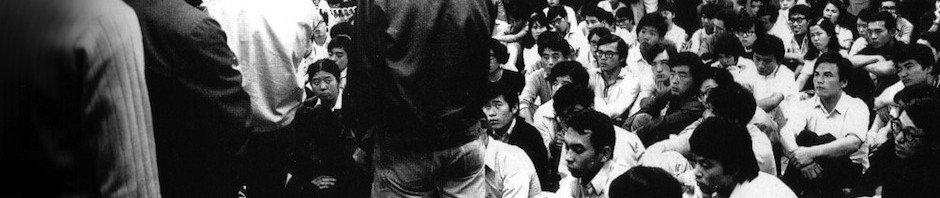

Now scroll up and take a look again at the banner image for this website. Hard as it might be to believe, this was taken by a Mainichi Shimbun press photographer in July 1969 at Shinjuku Station, at what was then called the Nishiguchi Chika Hiroba — the West Exit Underground Plaza. The masses of people are sitting down. They are listening intently to something. No one is rushing off. They have occupied the space.

The image was taken during a phenomenon that occurred at Shinjuku Station’s West Exit Plaza over the spring and summer of 1969, started by impromptu anti-war concerts held by musicians associated with Beheiren, the civic activism group led by Makoto Oda that campaigned against the Vietnam War and famously helped American deserters. The band of musicians were known as the “folk guerrillas” and their gigs turned into weekly rallies and demonstrations that took over the public sphere in Shinjuku.

This June saw the publication of a book about the movement, 1969 Shinjuku Nishiguchi Chika Hiroba (1969: Shinjuku West Exit Underground Plaza), and it included the first commercially available DVD of a rare documentary film made about the events at the space that year. The book is mainly made up of a long joint interview with Shigeru Ōki, a photographer, and Seiko Ōki (née Yamamoto), who was one of the folk guerrillas, and also includes several other short essays and the script for the film.

The book’s publication comes at a time of massive revived interest in 1960’s Japan, both domestically and abroad, as the Baby Boomers retire, and as the current situation in Abe’s Japan offers chilling parallels. In the past few years we have seen a veritable mini industry of memoirs, magazines and other books published about the protest movements and developments from the counterculture scene and experimental arts in the period. It feels significant, though, that this new book consistently draws on Beheiren’s original resources alongside quotations from Eiji Oguma’s 1968, the mammoth two-volume book that was one of the most hyped examples among the recent wave of publications about 1960’s Japan. Despite the accolades, it has been criticised by some since Oguma, who hails from the generation that came after the Baby Boomers, assembled his magnum opus purely through textual research, rather than interviewing actual participants. Its inclusion in 1969 Shinjuku Nishiguchi Chika Hiroba, edited and made by the original activists, further confirms its place, though, as the standard reference text on the era.

There is very little written about the Shinjuku folk guerrillas in English. They get a few (inaccurate) references in Julian Cope’s Japrocksampler: How the Post-war Japanese Blew Their Minds on Rock ‘n’ Roll, and also appeared in a 2008 PhD thesis by Peter Kelman, a paper by Ai Maeda, and briefly, in Thomas R H Havens’s valuable book about Beheiren, Fire Across the Sea: The Vietnam War and Japan, 1965-1975 (1987). By coincidence, though, the performing arts scholar Peter Eckersall published Performativity and Event in 1960s Japan: City, Body, Memory late last year and it includes an essay on the documentary about Shinjuku Nishiguchi Hiroba, based on an earlier paper that appeared in the journal Japanese Studies in 2011.

Keiya Ōuchida’s ’69 Spring-Autumn Underground Plaza

Also known as Chika hiroba (Underground Plaza), ’69 Haru-aki chika hiroba (’69 Spring-Autumn Underground Plaza) was filmed in black and white on 16mm, and first shown in 1970. Shot by director Keiya Ōuchida as a one-man crew, handling both the camera and sound recording (with some unsatisfactory technical results that make it into the final film with suitable cinema vérité panache), it was made at a time when such leftist documentaries and dramas were very much in vogue (see Ōshima, Ogawa Pro, Tsuchimoto, inter alia). Ōuchida (1930-2003) was the ideal documenter of the guerrillas and their disciples as he was slightly older than them; he could take a step back and focus on the phenomenon without getting directly involved. (The people from the time remember him as being like “an older brother”.) His career as a director was less spectacular compared to the likes of Tsuchimoto but did produce an output of many socially-engaged documentaries, including one in 1964 about the 1955 Matsuyama incident, a murder trial which was later proven a case of wrongful conviction. (It was one of four major murder cases in the early post-war period whose guilty verdicts and death sentences were overturned in the 1980’s.)

Ōuchida made his film about the folk guerrillas at a time when there was increased pressure against freedom of speech, especially film-makers. In July 1968 an Ogawa Pro cameraman was attacked by the riot police and later the anarchist writer and activist Rō/Tsutomu Takenaka was arrested while filming a documentary about the day labourer district of Sanya. Regardless if the leanings of the director were sympathetic to his or her subjects, with this kind of work the danger always lurked of it being seized by police and potentially used as evidence in trials. Police had been known to confiscate films in this way and in fact Ōuchida’s was screened at later trials. Ultimately, it was shown only a handful of times in public. Enough years have now gone by to make legal repercussions unlikely and we can also look back at both the folk guerrillas and Ōuchida’s film with the benefits of hindsight, knowing what happened to both the Japanese New Left and the anti-war movement in the 1970’s.

While obviously filmed on a shoestring, Ōuchida’s documentary captures the peak of the movement in the last weeks of the gatherings in Shinjuku. That being said, the approach is oblique at times. Its footage is punctuated by solemn narration, bordering on the didactic, asking questions (“Why is the plaza attacked?”) or making pared-down introductory statements. There are no interviews; it is documentary in a fairly literal sense of the word. It focuses on the phenomenon itself, the singing, the crowd, the mass. For all its concrete megaliths, Tokyo is always an organic hive. Such an observation is a cliché, the stuff of a hundred time-lapse videos cluttering up the broadband of YouTube and Vimeo. And yet it is clear here, even in the underground chambers of the city, that the citizens of the metropolis are buzzing, are untameable. Eckersall borrows from Shunya Yoshimi and says the documentary depicts scenes as a “social dramaturgy”. “We can read the images of protest at Shinjuku Plaza [sic],” Eckersall writes, “captured so viscerally in Underground Plaza, as performances. Bodies mingle and sway in time with the songs, people link arms in moments of solidarity, and they unfurl banners and chant slogans in unison.” The folk musicians themselves actually make relatively few appearances. They are not the stars; it is a document of the multitude that gathered every Saturday evening in Shinjuku, ostensibly to hear the anti-war songs but also to demonstrate and debate. Eckersall draws a comparison with the Greek notion of civic agora, a place of gathering, as opposed to the acropolis, the “upper” place of the gods and rulers. With the Tokyo Metropolitan Government building now literally almost overshadowing the west side of the station, Eckersall’s parallel is even more apt than it is for 1969.

Much of the time the camera lingers on the various inhabitants in the plaza at the weekly assemblies. Activists and citizens debate (quite politely, very seriously conducted in small circles). The camera wanders over demonstrators, signs, dialogue — the effect is hypnotic, emphasised by the eerie synthesizer sounds that form the soundtrack in lieu of music (Eckersall compares this to Godard’s Alphaville and its depiction of a techno-surveillance police state). Later there are clashes with the riot police as oppression grows. Officers rush in, dressed to the nines in all their combat gear, and make arrests of certain activists or disperse the crowds. Tear gas is fired. Some sectarian demonstrators react by lobbing stones at the station’s police box.

The Plaza

Like now, the space was essentially a passageway or thoroughfare, rather than a real plaza. It was a place for interchange, literally half open and half closed (sealed), since it was “underground” but with part of the roof clear for the double ramps. The plaza was quite new, completed in late 1966, though the west side of the station building itself had been finished earlier, in time for the 1964 Olympic Games. It was as such a new kind of urban space (such plazas were then and still are relatively rare in Tokyo). The whole west side of Shinjuku was far less built-up in the late 1960’s and the plaza was novel: a mosaic tiled “underground plaza with sun and fountains”, as the copy had it, with room for 433 cars in the second basement level, and linking the upper Odakyu and Keiō lines with the lower National Railway (JR) station, and the bus terminal at ground level. As such, the plaza was a ripe venue to host Japan’s Summer of Love.

Beheiren had an established association with folk even before the folk guerrillas started their concerts in Shinjuku. Folk as a professional musical genre (and as a form of protest song) had finally arrived in Japan in the late 1960’s with the likes of “Sanya Blues” and “Tomo yo” by Nobuyasu Okabayashi. “Tomo yo” (Friend) became, like “We Shall Overcome”, the anthem for the zeitgeist, as popular in Japan as the slightly earlier “Blowin’ in the Wind” was for Americans. (Try it out. Ask a Japanese person in their mid-sixties or older if they know the lyrics.) The folk guerrillas liked to sing “Tomo yo” and “Kidōtai Blues” (Riot Police Blues), a reworking of the melody from Tomoya Takaishi’s popular 1968 song “Jukensei Blues” (Entrance Exam Student Blues).

The folk guerrilla musical “rally” itself lasted around an hour. After the guitars had been packed up, the plaza became a “free” space for people to debate, do zigzag demos (a common student activist protest trope from the era), and hawk political leaflets. In a sense today we might call the folk guerrilla gatherings flash mobs. Shibuya Station’s Hachikō Scramble Crossing, this ain’t. Sectarian radical or nonpori (non-politicized citizens), older people and those who opposed the activists: all were welcome at the plaza and free to argue their point. As Ōuchida’s film also makes clear, even children and foreigners passed through. It was a festival consuming passersby and bystanders by its occupation of public space. It was a sit-in demo yet most of the protestors were on their feet to talk about the Vietnam War or sing. Perhaps the only time people sat down was to listen enthusiastically to the actual folk concerts themselves or to prevent the security from dispersing them, though this proves unsuccessful — after which Ōuchida’s narration chillingly quotes Japan’s Constitution and its supposed guarantees of freedom of speech and the right to protest.

As a space, it created a people’s “liberated quarter” (as was written in graffiti on the pillars of the plaza), a key concept for the Zenkyōtō generation, emulating what the French students had done in Paris. As a Beheiren newsletter wrote in June 1969, shortly after the first serious incursion by the police, boldly declaring the space as belonging to the people: “The West Exit Plaza is everyone’s. It is a place where anyone can freely profess their will. The person selling poetry or the person fundraising — there must be no distinction between Left and Right in that freedom. And in a way there was this freedom in the West Exit before. This scene is one that anyone who has ever passed through the West Exit knows. And so just why is this a ‘bad’ thing?”

Its genesis was as a music event but it took on the guise of agitation, with lots of individual demonstrators and discussions raging, somewhat like Speakers’ Corner in Hyde Park, London. Posters were put up, political slogans splashed on the walls and pillars. It became a de facto demo; people sold things, did fundraising, gave out pamphlets. There were hunger strikers from the Kaseitō immigrant rights group; factions like Chūkaku-ha and Shagakudō were present in their helmets and with flags. Its regularity every Saturday evening made it popular too, plus it was a way to communicate and get closer to peers — all very important in a non-digital age of more limited tools for dissemination.

It is important to keep in mind that the folk guerrillas themselves did not sing “The Internationale” et al; the overt agitation came from their audience. The actual famous folk singers like Okabayashi and Wataru Takada did not play at the rallies. The folk guerrillas were performative and political, but were they successful musically? This is a tricky distinction, since the nature of the events required them to sing loudly and no doubt sacrifice some melodic subtlety in the name of mass communion. Taku Hotta, one of the guerrillas, admitted that as time went by the politicality of the events overtook the musicality. Takada was especially critical of the folk guerrillas for the media hype and the elitism that came with the political kudos of being “wanted” by the cops. While it would be churlish to accuse the musicians of insincerity, it is safe to say that not all their peers admired what they did. (Beheiren in general also attracted quite a bit of flack over the years for its stunts and its penchant for celebrity endorsement.) Eckersall’s take on the performative side of the rallies is to consider them an example of “misperformance” in the mega-space of Shinjuku. What is customarily a post-war node for consumption, power and activity was utilized for events that worked “against the intended and authorised use of space”.

The Rallies

Concerts. Performances. Demos. Rallies. Riots. The folk guerrilla events encompassed all these definitions — and many more.

The rehearsal for Shinjuku, so to speak, were the gatherings in Osaka in the underground passageways of the Umeda district in the north of the city. These continued independently of the Tokyo rallies, though the nature of the Osaka ones were restricted by the nature of the space itself as a passageway rather than a plaza. There were also other folk guerrilla-esque events before the Nishiguchi ones. Accounts disagree over the exact day but it is clear the first Shinjuku folk guerrilla rally happened in late February. There were around ten main Beheiren “guerrillas” involved in the musical aspect of the events, although the leaders were clearly Seiko Ōki/Yamamoto (probably the most iconic member), Hiroshi Oguro, Shinnosuke Izu and Taku Hotta.

The rallies then grew weekly until there were several thousand people attending by mid-May. It was at the May 17th gathering that the riot police first appeared and dispersed the 2,000 people. Singing and fundraising in the plaza had been banned three days earlier and for a time people moved over to the east side of the station instead. In June the rallies got bigger and the police kept guard, but did not interfere. On June 21st there were 20 singers and eight main guitarists. But then on June 28th, after the concert was over, people went to protest nearby against the introduction of post office sorting machines. 800 riot police officers were deployed, firing tear gas to break up the crowd, who responded by attacking the police box at the West Exit Plaza.

Now the folk guerrillas and their fans were on borrowed time. The Beheiren offices were raided the next day and on July 4th, Izu was arrested at his home. Hotta was arrested on the street on July 5th, though the rally that day still went ahead, attracting 6,500 people. The last true rally was on July 12th, with 7,000 people crowding into the plaza or looking down from the ramps. On July 14th, Ōki/Yamamoto was arrested at her job at a publisher. On July 18th the name of the plaza was officially changed to Nishiguchi Chika Tsūro — the West Exit Underground Passageway. Although by default the plaza functioned as a passageway, now the authorities had the raison d’être to make their move, since in a passageway it was forbidden to stop and congregate. On July 19th, 2,200 riot police immediately broke up the thousands of people who had come to the “passageway” that evening. Oguro was arrested; he would be charged, along with Izu, on July 22nd. On July 24th, the police confirmed that the West Exit Underground Plaza could be defined by the traffic laws as a road. 2,200 riot police were on hand to prevent a folk guerrilla rally on July 26th. The phenomenon in Shinjuku was over.

Izu and Oguro faced a long four-year trial, during which their band of supporters grew thinner and thinner. So much for being folk idols. For the authorities, with the carnage of the International Anti-War Day of October 21st, 1968 still fresh in their mind (and which would be repeated in 1969, with Shinjuku an epicentre as always), they did not want to take any chances of rioting breaking out in Tokyo’s then premier commercial district. It is also not incongruous to put the folk guerrillas alongside the real guerrillas like the Sekigun-ha, the militant Red Army Faction that was gearing up for a series of violent actions in Tokyo and Osaka in late 1969. As far as the authorities were concerned, these were dangerous times and the difference between the folk musicians and New Left provocateurs was merely academic.

Ōuchida’s film ends, after a flurry of footage of clashes, with masses of police on guard at the plaza, making endless announcements into loudspeakers — “do not stop, please walk”. All around them people shuffle past. Guards would remain at the plaza like this in the following weeks, the graffiti gone from the walls. The film frames the plaza’s “suppression” in the context of the student and anti-war movements at the time, by also showing footage from the fierce clash at Haneda Airport in November 1967 where radical activists unsuccessfully tried to prevent the Prime Minister from leaving for talks with Japan’s American allies.

After the Party

What happened to all the thousands of people? 7,000 gathered at Shinjuku Station and then after the fun and games were spoiled by the party-pooping police, where did they go? The radicals in their helmets went onto bigger and better things. The anti-war demonstrators continued campaigning with Beheiren until the group dissolved in the mid-1970’s. But the “ordinary” participants seemed just to dissipate back into the swirling crowds of the city. The space was gone; the opportunity to segue from bystander to demonstrator and debater had been taken away.

As they had been doing during the height of the Shinjuku rallies, the folk guerrillas themselves held more rallies at other places in Tokyo such as Shibuya Station and Hibiya Open-Air Concert Hall, but with less spectacular results. Folk music continued to appear at Beheiren demos and anti-war concerts, including contributing to the Hanpaku, the alternate expo event in Osaka Castle Park organised in protest at the upcoming 1970 World Expo. The music, at least, carried on, but the unique space the folk guerrillas had started at Shinjuku’s West Exit Plaza was never replicated.

In 2003, Seiko Ōki went back to the West Exit Plaza to protest the Iraq War, holding up a placard with the famous Beheiren slogan Korosu na (Don’t kill). She attracted a following and is now a regular demonstrator there and elsewhere. Today her website is her “plaza”, as she says in the book, fulfilling the same function as the physical space did.

The folk guerrillas are one of the many reasons why Shinjuku is celebrated as the period’s centre of the counterculture scene, extolled most manifestly (and magnificently) perhaps in Diary of a Shinjuku Thief. Japan’s famous hippies, the fūtenzoku, also chose Shinjuku as their grazing ground, though they stuck to the East Exit side. When it comes to their legacy, we need to be careful not to eulogize overly or wax lyrical (excuse the pun) about the folk guerrillas. Ultimately, despite their pretensions to a horizontal, non-sectarian approach and a promotion of pacifism, the rallies were still hijacked by more extreme radical protestors, and then suppressed by the police. Japan’s role as a silent partner in the Vietnam War continued unabated. That being said, it is nice to know that a nascent Occupy Shinjuku existed, even if only briefly.

Tokyo is forever in flux. The Shinjuku Station plaza changed physically and those who remember 1969 say it feels much smaller now. There is no slope for peering down onto the plaza like before. The homeless community was forced out. The fountain no longer runs. Ironically it is still called “Nishiguchi Hiroba” in many signs but is it today a passageway or a plaza? Do the commuters and shoppers hurrying through it in their tens of thousands every day stop to think about it? Shinjuku was later the first place in Tokyo to have a pedestrianized shopping street, another kind of plaza — but one which had strict controls on it regarding demonstrations and performances. The authorities began to mould and curb the cityscape as they took the public space away from the dissenters.

That being said, Shinjuku Station today remains a site for demos and political gatherings. There are often people with placards at the West Exit Plaza (or whatever it is now called) and protest marches may start from in front of the East Exit. The station also still has its music, though the scale is smaller. Individual buskers can frequently be found nightly outside the West and South Exit. But the pillars that once had “liberated quarter” so flagrantly written on them are more likely to host advertising posters, and the whole “plaza” feels narrower, more filled with “stuff” — eateries, kiosks — than it must have done in 1969.

As the city gears itself up for the 2020 Olympics, the various districts are getting their revamps. Marunouchi is an oasis of gleaming vast glass complexes. Kanda Station is a massive construction site. Kabukichō and Shimokitazawa, both neighbourhoods with their own distinct brands of counterculture, are being “scrubbed” clean of their untidier elements, on the surface at least. Music is once again at the heart of protest movements in Japan, such as the anti-government and anti-nuclear power demonstrators, as Noriko Manabe’s research is showing. But once the dust from Tokyo’s earnest makeover has cleared, will there be any room left for these new folk guerrillas?

WILLIAM ANDREWS

Hi I loved your article. Bit of a random question but I am desperately seeking this book and/or DVD but with no success. You couldn’t point me in the right direction could you? I live in Tokyo.

Thank you

LikeLike

@Zoe

You should be able to pick it up from Mosakusha in Shinjuku.

LikeLike