“Trotskyist” is a word rarely heard in Japanese leftist circles these days and not so long ago it was commonly used as an insult. This was especially the case with the Japanese Communist Party (JCP), which employed the term to disparage its upstart New Left rivals in the post-war period. But who were the Trotskyists?

In March 1956 Fourth International in Paris urged activists in Japan to form a local branch of the Trotskyist network. This challenge was taken up by former and current members of the Japanese Communist Party, who had grown disillusioned with the Party. In July 1955 the Sixth Japanese Communist Party Congress saw the JCP embrace peaceful and legal means to revolution. It was a major turning point and the reaction was the birth of the New Left in Japan.

Nihon Torotsukisuto Renmei (Japan Trotskyist League)

The Nihon Torotsukisuto Renmei (Japan Trotskyist League) was formed in 1957 as an alternative to the JCP, which had abandoned armed struggle and mass revolution, and in the wake of the Hungarian Revolution. This almost immediately went through a rebranding in December 1957 as the Nihon Kakumeiteki Kyōsanshugisha Dōmei (Kakukyōdō) (Japan Revolutionary Communist League) and later broke up, in part over the question of the league’s Trotskyism.

The league continued to morph a few more times, eventually forming into two separate factions — Chūkaku-ha (Central Core Faction) and Kakumaru-ha (Revolutionary Marxists) — in 1963, neither of whom would define themselves as Trotskyist. They emerged from Trotskyist ideology belatedly taking root in the Japanese Left in the post-war period. But thinkers like co-founder Kanichi Kuroda — ultimately the leader of Kakumaru-ha — were opposed to dogmatic Trotskyism and its strategies. Instead they followed an essentially Leninist ideology and wanted to build a strong proletarian party. They were defined primarily by their anti-imperialism and anti-Stalinism (in Japan, “Trotskyist” was a label applied to any anti-Stalinist), and their commitment to a purer Marxist approach, which they believed the Japanese Communist Party had deviated from.

But Japanese Trotskyism did not die.

Ryū Ōta, one of the most fascinating characters in the pantheon of the New Left in Japan, had left the Revolutionary Communist League early on (the “first split” in 1958) but remained fiercely committed to the world communist revolution. He formed another Trotskyist association in 1958, which later became the Kokusaishugi Kyōsanto (International Communist Party, or ICP). Ōta attempted French Turn-style entryism into the Socialist Party, though with limited success.

During the second split (1959) of Kakukyōdō, a group based in Kansai had also broken away, leaving the remaining members to form a “National Committee” version. Led by Kyōji Nishi, who had experience in a early JCP guerrilla corps, the so-called Kansai Faction were full Trotskyists and supporters of the American Trotskyist James P. Cannon.

Fourth International Japan (Daiyon Intānashonaru Nihon Shibu)

Fourth International Japan (Daiyon Intānashonaru Nihon Shibu) was formed in 1965.

It came out of an earlier union of Ryū Ōta, one of the original founders of the Japan Trotskyist League, and his Michel Pablo-esque ICP, with the so-called Kansai Faction, who had already formed their own prototype Fourth International Japan branch in 1960.

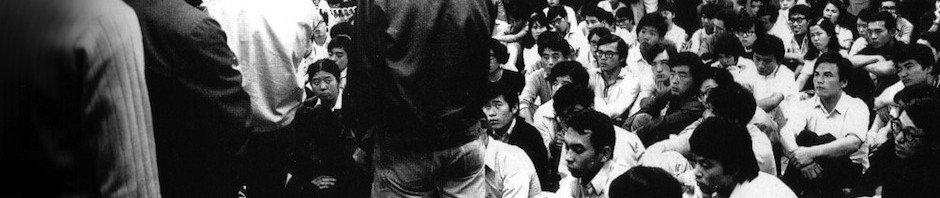

Fourth International Japan was then the only true major Trotskyist organisation in Japan. It was instrumental in certain movements, such as the campaign against the construction of Narita International Airport and campus struggles, including the University of Tokyo Zenkyōtō. Its most enduring and notorious achievement in the public eye is perhaps when it occupied the air traffic control tower at Narita shortly before the airport was to open in March 1978.

Activists wore red helmets with hammer and sickle insignia, and its organ was Sekai Kakumei (World Revolution). Its student base was strongest at several regional universities in the Tōhoku region of northeast Japan and at Sophia University in Tokyo.

Confusingly, it also called itself Nihon Kakumeiteki Kyōsanshugisha Dōmei (Japan Revolutionary Communist League), though was (and remains) known colloquially as Daiyon Intā or sometimes (more abusively) Yontoro.

While it was ingrained in the key localized conflicts in Japan as part of a “far east liberation revolution”, it was distinct from its New Left peers not least in its purist Trotskyist ideology but also its avoidance of the bitter infighting (uchi-geba) that proved so destructive for the New Left movement during the 1970s.

That being said, it had initial teething problems and internal disorder from the start with members who had taken part in Ōta’s entryism. Fourth International Japan had to rebuild its organisation during the late 1960s and early 1970s, and it was perhaps strongest during that decade, as symbolised by its significant contribution to the Narita campaign. (Always the loner and renegade, Ōta himself also very quickly left Fourth International, ultimately drawn away from Trotskyism and Marxism towards theories of a mondial Lumpenproletariat revolution during the 1970s, but that is a whole other article.)

Fourth International Japan began to split formally in the late 1980s, with some breakaway groups leaving the fold after a rape scandal (known as the “ABCD Mondai”, or the “ABCD Problem”). It was reformed and renamed in 1991 as Nihon Kakumeiteki Kyōsanshugisha Dōmei, the Japan Revolutionary Communist League (JRCL), dropping the Daiyon Intā (Fourth International), with a weekly organ, Kakehashi (Bridge, Intermediary). Since then it has openly discussed problems of sexual discrimination and rape, a major issue for many years in the New Left in Japan.

It was removed from the United Secretariat of the Fourth International (USFI) in 1991 and so is now only a sympathizer group (Permanent Observer Group) in the wider Fourth International movement. Kakehashi is co-edited with another faction, Kokusaishugi Rōdōsha Zenkoku Kyōgikai (National Council of Internationalist Worker).

Like all the New Left factions, infighting, changing times and the inevitable ageing of its membership has greatly reduced the fortunes of Daiyon Intā, though even as late as 1988 the police claimed the group had 2,000 active members. They continue to publish and protest.

Kyōsandō (Bund) (Communist League)

Kyōsandō (Communist League, also known as the Bund) is also often classified as Trotskyist by default of being opposed to the Japanese Communist Party. Formed in 1958, its student wing came to dominate the Zengakuren league of student councils in the late 1950s and early 1960s. However, it subsequently split countless times following the first Anpo struggle and its sway over student activism disintegrated, brief resurgences of unity under the anti-war banner in the later 1960s notwithstanding.

Almost none of the factions remain today and it was ultimately succeeded in influence by Kakumaru-ha and Chūkaku-ha, and Kaihō-ha (whose origins lie in the Japan Socialist Party). In truth, outsiders would probably regard Kyōsandō as more Blanquist than Trotskyist per se, and perhaps its greatest legacy is that it was the progenitor of Sekigun-ha (Red Army Faction), whose internationalist ambitions did indeed have a Trotskyist flavour but turned out to be in a genus all of their own.

Other Trotskyist Factions

Other Trotskyist factions in Japan include Spartacist Group Japan, part of the US-based International Communist League (Fourth Internationalist). Its organ Spartacist Japan was first published in 1982. Very little information about the group is available and it does not appear to be currently active.

WILLIAM ANDREWS

This is teh current link to teh section. There was also a womens group who have status over a dispute. http://www.jrcl.net/

LikeLike

@Jim Monaghan

Yes, the splits in the late 1980’s/1990’s led to several splinter groups, including the women’s liberation group.

I actually avoided links because most of the groups do not have English websites. Thank you.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on bolshevikpunx.

LikeLike

Interesting. I will read some more of your writing. I was active with the JRCL – 4th Inter from 1974 to 1978. We had a small foreigners’ section: 2 Americans, 1 Brit, and me (a Canadian). Among other activities, we produced a pamphlet about Narita. Another campus where we were strong was Shibaura Technical University (at Tamachi). Also, the 4th Inter group did lead and organize the take-over of the control tower, but it was a co-operative action with members of some other organizations. We also had a magazine called Fujin Tsushin, which covered women’s activism. I was also active in the National Union of General Workers (Zenkoku Ippan) at that time.

LikeLike