The freedom to make and remake our cities and ourselves is … one of the most precious yet most neglected of our human rights.

David Harvey

On the afternoon of January 22nd, a small protest of some 80 people set off from Harajuku in central Tokyo. The marchers were demonstrating against the upcoming Summer Olympic and Paralympic Games, which will be held in Tokyo in 2020. Shortly after departing, a protester allegedly got into a scuffle with one of the police officers regulating the march (protests in Japan are often heavily policed) and was arrested for obstructing the performance of official duties. Though the activist was released without charge two days later, it was reported by the right-leaning Sankei Shimbun newspaper as an “assault on a police officer” while campaigners called the arrest “unjust.”

Rio is over and the Tokyo Games are fast approaching. However, the initial fanfare in Japan has been far from positive and the preparations criticised by many sections of society. Part of this has been spearheaded by a growing anti-Olympic movement in Tokyo, best represented by the publication last year of a Japanese book, The Anti-Olympic Manifesto, which quickly sold out its first print runs.

Troubled Preparations, Troubling Nationalism

There is a curiously wistful wind surrounding the upcoming Olympics. The movers and shakers of the 2020 Games are baby boomers nostalgic for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, which heralded Japan’s emergence from post-war hardship and helped usher in the start of a period of high economic growth. The slogan for the upcoming Olympiad is “Discover Tomorrow” but perhaps it should be “Remember Yesterday.” Those halcyon days are long gone and will never be reclaimed, given the demographic reality of Japan and the world economy. But that does little to deter the dogged seniors, who are determined to hijack the event for nationalist agendas.

Almost every major corporation or public project now name-checks “2020” while the government simultaneously pursues a big push to increase inbound tourist numbers, all shrouded in the mantra of “omotenashi.” Essentially meaning “hospitality,” this word was used effectively in Tokyo’s final bid presentation for the 2020 Olympics and has since become the go-to phrase for tourist services against a backdrop of heightened nationalism in television broadcasting and a government intent on railroading right-wing bills through parliament. In addition, areas of Tokyo are currently undergoing massive levels of redevelopment, especially Shinjuku, Shibuya and Marunouchi, with the result that every few months witnesses the opening of yet another large commercial complex or glass tower.

This buoyancy is at odds with much of the concrete build-up for the Olympics, which has been tainted by scandals and setbacks. In May 2016, The Guardian published allegations of bribery during the bid process. The original logo was withdrawn when the designer was accused of plagiarism. The new national stadium proposal by the late Zaha Hadid was scrapped after an outcry over budget overruns. And the plan to relocate the world-famous Tsukiji Market to Toyosu on the other side of Tokyo Bay, in part to make way for Olympic facilities, but this immensely expensive project is currently on hold due to contamination at the new site. This threatens not only the reputation of the world’s largest wholesale fish market but also the entire construction countdown until the opening.

And then there is the problematic promise by Prime Minister Shinzō Abe that the situation at Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant is “under control,” made during the omotenashi-painted presentation in Buenos Aires in 2013. For many anti-nuclear power campaigners, this is not the case at all and holding the celebratory Games in the capital is anathema when so much of the northeast of the country remains in need of reconstruction and assistance after the 2011 tsunami.

In addition to the albatross that is Fukushima, the main complaints against the 2020 Games centre on the spiralling costs and waste of funds. The constantly ballooning budget for the Games was recently projected to be 3 trillion yen ($29 billion), which is more than four times the original estimate provided when Tokyo was awarded the Olympics. The controversy has prompted organisers to relocate events out of Tokyo — even Fukushima is being considered as a host for some. Campaigners are also angry that construction firms are being handed big contracts while the homeless and poor are “cleansed” from certain areas.

That said, the Rio Games were a great boost for the Olympic team’s morale. Japan’s record medal haul has helped shift public opinion. According to press reports, some 800,000 people attended a homecoming parade in central Tokyo for the athletes on October 7th, 2016, which, if accurate, would be dwarf any street protest in Japanese history. (The media also said 500,000 attended the 2012 parade.) The handover ceremony, featuring the prime minister dressed as Mario, was generally well received.

The Anti-Olympic Manifesto

The Anti-Olympic Manifesto is a 269-page paperback back that joins a growing body of texts about anti-Olympic movements, including Celebration Capitalism and the Olympic Games, Activism and the Olympics: Dissent at the Games in Vancouver and London and Power Games: A Political History of the Olympics by Jules Boykoff, Barbaric Sport: A Global Plague by Marc Perelman, Five Ring Circus: Money, Power and Politics at the Olympic Games, edited by Alan Tomlinson and Garry Whannel, and Five Ring Circus: Myths and Realities of the Olympic Games by Christopher A Shaw. It is also possible to find examples of discourse in Japanese going back to 1980s due to the bid for Nagoya to host the 1988 Summer Games, not least a similarly titled “anti-Olympic manifesto” published in 1981.

Edited by Hiroki Ogasawara and Atsuhisa Yamamoto, several of the essays in the book are translations of articles by the likes of Terje Haakonsen (the snowboarder who boycotted the Nagano Olympics in 1998) and the prolific Boykoff. Likewise many of the case studies are drawn from international examples. This gives the book not only an overtly ideological tone against neoliberal gentrification in general but also puts the discourse against the Tokyo Olympics in a global context. The publication is significant for documenting aspects of the arguments against the 2020 Games and its side effects on overlooked elements of society, but also showing how the movement against 2020 fits into a history of similar campaigns. That being said, much of the content is quite dense and academic, which may well limit its readership.

It may well find itself running against the zeitgeist. The publisher was actually unable to advertise the release of The Anti-Olympic Manifesto properly at some universities, even though many of the contributors are academics.

Opposition to the Tokyo Olympics and Redevelopment

So far the street-level movement has centred on the homeless and the impact of preparations for them, though there is a disconnect between this and the parliamentary discourse. The large opposition parties like the JCP are not very vocal except on issues such as the rising costs and Toyosu problems, while far-left groups have focused on how these cost overruns expose the iniquity of capitalism and the health risks to workers posed by the Toyosu relocation. They say that Governor Yuriko Koike is trying to force the blame onto other bureaucrats while pursuing her own agenda of privatisation and union-busting.

The 2020 bid actually highlighted how these would be a “green” and compact Games with little need for construction or development, since 1964 Games facilities and other infrastructure could be utilised. In reality, the bay area has seen massive redevelopment, in part commercial land that real estate companies hope will sell as condo units for greatly inflated prices with the prestige and better transport links brought to the area by the Games.

Other development focuses on the Meiji Park and Sendagaya area, where there are several public sports facilities. The old National Stadium has now been knocked down and the new one (sans the Zaha Hadid design) is being built, and the development work has subsumed neighbouring Meiji Park. This affected the dozens of homeless who lived in the park (in Japan, homeless people frequently live in self-made shacks in public parks), and long-term residents in a government housing project, Kasumigaoka Apartments, who were mostly elderly and did not want to leave.

Emerging from protest groups opposed to the (failed) 2016 and (successful) 2020 Olympic bids, there are now two main groups in the anti-Olympic campaign that are interconnected: Hangorin no Kai (literally, Anti-Olympics Group) and Supporters for the Park Residents around the National Olympic Stadium.

Hangorin was formed in January 2013. Temporary evictions and expulsions of the homeless from Meiji Park started in 2013 during the IOC inspection tour. Tokyo government employees reportedly came to tell some of the homeless mere days after Tokyo won the bid that construction would start in late 2013 and that they should leave as soon as possible.

Japan Sport Council, borrowing land from the city at no cost, began intensifying the eviction process along with Tokyo Metropolitan Government from January 2016, when around 200 JSC employees, police and security personnel descended on the park to forcibly remove the homeless. In March, Japan Sport Council put up cameras and one person was arrested. In April, more evictions led to another arrest.

For now, a handful of homeless remain in tents in a patch of grass opposite the development site. Though divided by a road, this is technically part of Meiji Park and the land is earmarked for a hall. Signs and rope around the entrance warn that entry is forbidden, but people were free to walk in when this writer visited in late 2016. Nearby, the fabulously dilapidated Kasumigaoka Apartments — government housing that dates back the 1960s — are being torn down and all residents evicted. According to an NHK report in 2015, there were 200 residents in the apartments. It is a somewhat sad irony that some of the people living there had actually moved into the area after their original homes were knocked down to make way for construction during the preparations for the 1964 Games in Tokyo.

By July 2016, Hangorin had already organised seven protests in Shinjuku and Shibuya. They have few allies in mainstream media or politics, with the notable exception of anti-nuclear power lawmaker Tarō Yamamoto. They have been attempting to learn from the anti-Games movement in Rio and one campaigner went to observe the protests first-hand.

Opposition to Gentrification

These activities overlap with the general anti-homeless, anti-gentrification movement in Tokyo. The government has already been trying to cut down the numbers of homeless for some time with a new housing scheme. One of the most despised endeavours in recent times was the Miyashita Park project in 2009, when Shibuya ward attempted to privatise a public park and sell its naming rights to Nike. The small park borders the main shopping and commercial area in Shibuya, and as such there was a conscious decision to shut out the unsightly homeless residents spoiling the atmosphere of the district.

Though the fight against the renaming won, the park was nonetheless turned into a sports facility, and the Shibuya ward government continues to shut the park at night in order to keep out the homeless. The fencing around Miyashita Park is often “artjacked” with posters, leaflets and pictures protesting the Olympics and the treatment of local homeless community.

Significantly, Shibuya is run by a former ad man who is determined to brand the ward in a certain way. Part of this was the decision by the ward to give tacit legal recognition to same-sex couples, which was rightly applauded and attracted much positive press. However, the voices of less appealing marginalised groups such as the homeless are ignored. There are even new plans for Miyashita Park as part of a massive redevelopment scheme for Shibuya unfolding over several years. It will soon be overshadowed by the opening of a complex called Shibuya Cast.

Looking Back to 1964

As we can see from turning back to the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, massive development projects and attempts to “clean” the city are perhaps shared elements of any Games.

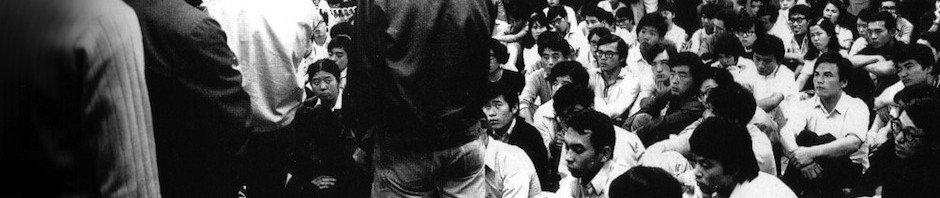

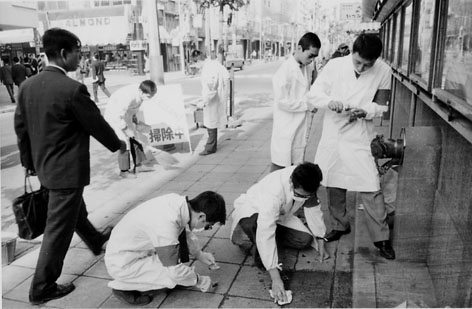

The Shinkansen bullet train link between Tokyo and Osaka was rushed through to be ready in time for the opening, so much so that the project ended up costing twice its original proposal. The botched planning of a monorail line led to the loss of fishing jobs, as Robert Whiting, who lived in Tokyo at the time, recalled in The Japan Times in October 2014. He also noted the use of cheap foreign labor, the bid-rigging and corruption as well as the environmental damage when rivers were concreted over. The city attempted to mobilise the population in the grandiose project, to some success: 1.6 million residents helped clean streets in January 1964. The avant-garde art unit Hi-Red Center, though, organised a stunt where they dressed up in white lab coats and cleaned the streets of Ginza, central Tokyo, to mock these attempts by the capital to spruce up its image for the world. The acclaimed Kon Ichikawa documentary film about the Games, Tokyo Olympiad, starts ominously with buildings being pulled down. This was somewhat subversive since it was actually the official film, and as such was disliked by the organisers.

Similarly, the 1970 World Expo in Osaka was the trigger for a mammoth infrastructure development program. A protest event called the Hanpaku (Anti-Expo) was held in Osaka Castle Park. However, little is remembered of opposition to the 1972 and 1998 Winter Olympics held in, respectively, Sapporo and Nagano.

2020: A Call to Arms

Given the example of Hi-Red Center, the arts may provide fertile examples of interesting dissent against the upcoming Games. So far, however, there have been almost no major interventions. The playwright and director Hideki Noda’s Egg (2012) was a prescient satire on “mega-events,” though it was ironically produced at the Tokyo-funded public theatre he runs and also with an extremely commercial cast. It was then revived in Paris in 2015. However, before Noda can be categorised as a genuine critic of the state and Olympics, we should keep in mind that he is ostensibly supervising the anodyne “preview” event of the Cultural Olympiad planned by Arts Council Tokyo. We can hope for some kind of robust response from the arts regarding the Olympics and its attendant issues, though many in the industry are likely first waiting to see what lucrative opportunities may arise to participate in the Cultural Olympiad.

So rather than the arts, we would be wise to focus on the Thin Blue Line: what will the police do, and whom will they be watching? Authorities have already beefed up security and surveillance measures at the Tokyo Marathon, including use of facial recognition technology, police runners with cameras and drones in the air. Such tactics will be honed and expanded for 2020. As we saw in the run-up to the G7 summit in 2016, we can expect a crackdown on far-left groups prior to the Games, though it is doubtful that these veteran radicals would mount an attack like they have at previous international summits in Tokyo (e.g. 1979, 1986) since the Olympics are not a political enough an event in and of themselves, notwithstanding the arrival of a few heads of state. In addition, police and the state will certainly want to enhance the surveillance of the population and various dissenting elements as well as the Muslim community, which is already under significant scrutiny. Quite how seriously it takes Hangorin and its ilk is yet to be seen. Already legal changes are quietly taking effect that greatly increase powers for wiretapping, not to mention the implications of the proposed conspiracy bill that will arguably give the state carte blanche to arrest people suspected planning certain crimes. And most importantly, we should not expect these surveillance or judicial measures to recede once the sporting events are done and dusted. It is very likely that the systems and tools will stay in place.

Up to this point, the presence on the streets has been relatively tame but actions are likely to escalate as we draw closer to 2020. (The next Hangorin no Kai protest is scheduled to take place in Shinjuku on February 24th.) We will also surely witness counter-spaces in areas like Shinjuku and Kōenji thrive as citizens dissenting from the collective boondoggle come together for events. You can even now get an anti-Olympic tote bag and such items will certainly multiply, providing a fitting antithesis to the coming flood of official merchandise.

There is also speculative talk of an “alternative Olympics”, as discussed in a book in 2015. The Olympics are, after all, a festival and like all festivals manifest a period of liminality, a time when social norms are upturned and citizens can reassert their right to the city. As such, the Games represent a golden opportunity for a 2020 Anti-Olympics event, a Hangorin — featuring, say, unconventional sports, music, dance and discourse — held in glorious disorder somewhere like Kōenji, which could come alive with Situationist-inspired détournement of street theatre, dérive and pranks, while the rest of the city and the nation (and the world) consumes the spectacle of the authorised games through television. The event would be overlooked, naturally, but it would fulfil a function that all healthy cities should allow: a space for ludic subversion from within.

The Olympics are an insurmountable behemoth, and one that cannot be stopped barring a major catastrophe, which protestors naturally do not desire. One thing is certain, though: not everyone in Tokyo will be celebrating when the Games open in July 2020. And they are sounding a clarion for dissent.

WILLIAM ANDREWS

Further Reading in Japanese (Selective List)

反東京オリンピック宣言 (2016)

小笠原 博毅 (著, 編集), 山本 敦久 (著, 編集)

東京オリンピック「問題」の核心は何か (2016)

小川 勝 (著)

東京2025 ポスト五輪の都市戦略 (2015)

市川 宏雄 (著)

PLANETS vol.9 東京2020 オルタナティブ・オリンピック・プロジェクト (2015)

宇野 常寛 (著, 編集)

東京五輪で日本はどこまで復活するのか (2013)

市川 宏雄 (著)

オリンピックと商業主義 (2012)

小川 勝 (著)

反オリンピック宣言―その神話と犯罪性をつく (1981)

影山 健 (著)

Groups and Organisations

反五輪の会

Hangorin no Kai (literally, Anti-Olympic Group)

http://hangorin.tumblr.com/

国立競技場周辺で暮らす野宿生活者を応援する有志

Supporters for the Park Residents around the National Olympic Stadium

http://noolympicevict.wixsite.com/index/blog

Planetary No Olympics Network

http://tokyo2020-rio2016.tumblr.com/

Irregular Rhythm Asylum

http://ira.tokyo/

Café Lavandería

http://cafelavanderia.blogspot.jp/