When Kyoto University announced on 19 December 2017 that the famously ramshackle Yoshida Dormitory could no longer accept tenants and that current occupants must vacate the facility by the end of September 2018, it raised many eyebrows among nostalgists who like to gush about its tumbledown charms. This is not just a question of Kyoto esoterica or sentimentality over a beloved facility, however, since the closure of Yoshida Dormitory means the loss of another centre for the Japanese student movement as well as, on a practical side, a resolutely cheap lodging for impoverished young scholars facing rising tuition fees and living costs, and stagnant part-time job wages in the harsh neoliberal landscape.

The run-down charms of Yoshida Dormitory at Kyoto University

“It is decrepit,” was one foreign observer’s verdict for Travel CNN in 2010, “but this building is no ruin. It’s the Yoshida-ryō dormitory — a bewildering anachronism in a city based on the idea of living history.” A stay at the dilapidated Yoshida Dormitory costs a mere ¥2,500 a month, part of which is paid to the independent students’ council that runs it and handles tenant applications. The new building was opened in 2015 but the older, wooden one dates back to 1913, and is certainly showing its age. Needless to say, the accommodation is frugal and hardly the cleanest, and rooms are shared. Hens roam freely around the garden and items of junk and litter copiously spill out all over the grounds.

Dormitories have traditionally been a student fiefdom in Japan, allowed to run themselves in the same way as the general student councils (jichikai) were granted significant autonomy in their activities (be they sports, clubs, politics, and so on). Control of the dormitories was quite a flashpoint for student groups back in the day. Times change, and so do universities. Private universities have always more strictly managed their dormitories, but public colleges are also today not necessarily the student “liberated zones” of lore. Administrators are no longer as tolerant of oddball dormitories that condone on-site behaviour likely to bring their institutions into disrepute. The Yoshida Dormitory Students Council was not consulted regarding the university’s announcement in December and has been excluded from the process to decide its future.

It is no coincidence that this move to close Yoshida Dormitory comes at a time of conflict with the student body over campus festivals, pranks and politically motivated stunts such as strikes. The Yoshida Dormitory strife also appears while another on-going controversy at Kyoto University rages over the signboards which students have long erected on campus to advertise clubs, events and various issues.

Such tatekanban were once common sights at Japanese universities and something of a symbol of the student movement, in addition to the more belligerent images of helmets, staves and towels covering faces. While they have not disappeared completely, their usage is reduced and for the most part less political in nature. Nonetheless, for some observers they are an eyesore, obstruction or even provocation, depending on the content. As previously noted, Kyoto University is pressuring students to remove signboards, in part due to complaints from local residents and a warning from the municipal authorities. This is not a sudden development per se and friction over the signboards has been brewing for some time, just as the discussion over closing Yoshida Dormitory is a long-standing one.

New university rules since 19 December define tighter conditions for signboards on campus. They include stipulations that only groups officially recognised by the university can erect a board and locations are limited to places designated by the administration. Signboards must be no larger than 200 x 200 cm, and removed within 30 days. Moreover, signboards can only be erected for the purposes of advertising to freshmen students between 20 February and 20 April, or for purposes related to November university festivals between 15 October and the end of the festivals.

The bureaucracy is sounding the death knells loud and clear, but the students are also not going quietly into the night. A new website has been launched celebrating the vibrant history of signboards at Kyoto University through photographs from across the decades. Here are some examples of signboards created by different clubs and groups over the years, neatly illustrating the verve and diversity encapsulated in tatekanban culture.

A large signboard in the centre of the campus in 1992, in front of the iconic Kyoto University Clock Tower Centennial Hall

A gay theme evident in this colourful signboard from 1994, advertising events including one with renowned critic and Kyoto University professor Akira Asada

A signboard of unknown date advertising a screening of the documentary YAMA — Attack to Attack, about the slum district of Sanya, superbly imitating the most famous image from the film

Different inspirations on display in these signboards from 2013

An anti-war signboard from 2015

Lively signboards in various shapes and sizes from 2017

The signboards archive is actually just one part of the website, which is conceived as a platform for disseminating information about the dormitory issue and what activists see as a crackdown on student freedom. These efforts are offline, too. On 13 February, a related symposium was held in Kyoto that attracted 450 attendees and press coverage from the Mainichi Shimbun and Yomiuri Shimbun newspapers.

In addition to submitting formal objections to the university’s plans, the Yoshida Dormitory Students Council also launched an online petition, which has attracted nearly 2,000 signatories to date, making the following three main demands (official English translation slightly adapted):

1. Withdraw the Basic Policy to Ensure the Safety of Yoshida Dormitory Resident Students, which was announced on 19 December 2017.

2. Continue the promise to the Yoshida Dormitory Students Committee (a written agreement maintained by successive vice presidents, which prescribes the university to have a dialogue with residents before it makes a decision on the dormitory) and consent to an open meeting with students.

3. Make a decision in regards to repairs to the old Yoshida Dormitory building in consultation with the Yoshida Dormitory Students Council.

The dormitory is, activists assert, a “safety net for students with financial difficulties” and “a cultural institution where a huge range of activities has taken place for over 100 years”. They urge the university to commit to renovations and repairs of the present structure rather than push ahead with the eviction and demolition plans, which will undoubtedly result in a very different kind of facility and, as a matter of course, the loss of the students’ right to run the dormitory themselves.

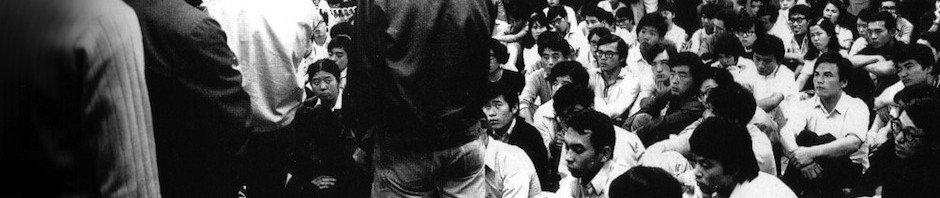

Kyoto University’s political heritage is strong, including an incident in the 1950s when students protested the visit of Emperor Hirohito. The institution was a fulcrum for the student movement in the late 1960s, hosting a much-chronicled strike and giving birth to such influential factions as the Kyoto Partisans and Sekigun-ha (Red Army Faction). Today, the university is engaged in a protracted dispute with students at the Kumano Dormitory, which is home to certain activists associated with a branch of the Chūkaku-ha Zengakuren student league. Since 2014, the tension has intensified due to the arrests of young activists in Tokyo and Kyoto, who are then invariably released without charge. These arrests then form pretexts for raids and phalanxes of riot police officers marching into Kumano Dormitory have become a familiar vista. An undercover police officer was rumbled on campus and Zengakuren activists held a mini anti-war strike, for which students were arrested and permanently suspended. The most recent case involves a fourth-year student, who has been permanently suspended as of 13 February for allegedly assaulting a security guard attempting to stop people not enrolled as students at the university from handing out leaflets near the gate on an open campus day in August last year.

Not to be deterred, each arrest or punishment only emboldens the left-wing students (and ex-students) further. Zengakuren is building a modest yet robust student movement, particularly at such universities as Hōsei, Kyoto, Tōhoku and Okinawa. It organises frequent marches and demonstrations in response to the efforts of police and administrators to hold its swell in check, while also honing its presentation from a “dangerous” and “militant” group into a self-parodic and humorous yet still ideologically serious association.

We should resist the temptation to consider this simply as a local issue. What is taking place at Kyoto University is indicative of a broader trend in Japanese higher education to “cleanse” campuses, especially at private colleges, where it is now much harder if not nigh impossible for political groups to maintain officially recognised student clubs. Universities such as Hōsei, Waseda and Meiji have made it their missions in the Heisei period to expunge the far-left factions that once recruited so successfully from student bodies. By removing their physical bases, expelling politicised students and banning their affiliated student councils, it prevents such groups from developing a new generation of activists and also cuts off a source of income. Public universities have been more restricted in what they can do in terms of curbing student autonomy and working with the police, but such inhibitions are evidently fading in the case of Kyoto, where police officers have now become fixtures around campuses and at Kumano Dormitory.

WILLIAM ANDREWS

I was drinking with a former Bund guy last night and he was raving about the new film “Occult Bolshevism” which is currently playing at Eurospace. If you haven’t seen it, please check it out before it closes!

LikeLike

@Avery

Thanks for sharing as always.

LikeLike