We begin with two scenes and two sets of very different agents of the Left.

Three men armed with revolvers entered the Ōmori branch of Kawasaki Daihyaku bank on October 6th, 1932. The men were, of course, bank robbers and they got away with 32,000 yen, a considerable amount at the time. The heist was well-planned by a senior Japanese Communist Party member, Yūshō Ōtsuka, among others, though it was executed without the approval of the Central Committee. The men wore khaki coats and used JCP theorist Hajime Kawakami’s younger daughter Yoshiko as a cover, having her drive with them in the getaway car in case they were followed by police. The robbery created a media sensation.

The JCP was at the time in dire financial straits, having lost its revenue from Shanghai the previous year and was existing precariously on the donations of fellow travellers and members. For a time it had even operated a dance hall in Tokyo to raise money.

The Ōmori bank job was the first of a series of heists. Though the raids achieved their immediate objectives, they also contributed to the final decimation of the pre-war JCP. With the state at the time already cracking down on the JCP, the robberies were perfect propaganda and justification for arresting hundreds of members and hunting for its clandestine leadership. Though the Akahata (Red Flag, the JCP’s newspaper) professed innocence, the police could label the Communists as gangsters. And with the help of spies in the JCP ranks, they had arrested almost all the leadership within two months, often brutally so at times — several arrestees were tortured and murdered, including the novelist Takiji Kobayashi.

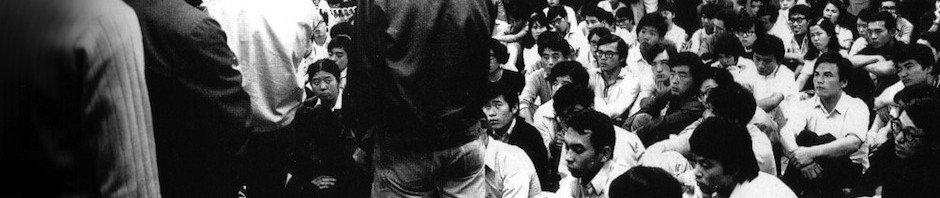

Now fast-forward to the 1970’s. The Japanese New Left has emerged and is at the height of its influence — and notoriety. In late 1969 yet another faction appeared that was to be the ultimate game-changer. The Sekigun-ha, or Red Army Faction, was led by a former philosophy student from Kyoto University and was openly advocating militant action to overthrow the state. Though many of its early behavior bordered on the amateurish, beneath all the inevitable rhetorical pomp the leaders of the small army were very serious about their cause. And their choice of tactics went way beyond the campus occupations and street battles of their peers. The Sekigun-ha launched a bombing campaign in Tokyo and Osaka against police facilities. The authorities began to clamp down, arresting a large number of the membership when they were training in Yamanashi for an attack on Tokyo. The commander-in-chief was nabbed by chance on the streets in early 1970 but then days later other key members of the clique pulled off the incredible Yodogō hijacking.

The Sekigun-ha still had relatively large numbers of troops it could mobilize for future campaigns. But it needed money. It had been funding much of its operations through contributions from academic patrons but it needed more as its ambitions continued to soar. Between February and July 1971 the Sekigun carried out over half a dozen robberies of banks and post offices. If nothing else, you have to give them credit for being brilliantly effective thieves.

One of the most famous is the July robbery of a bank in Yonago City in Tottori Prefecture, carried out by four armed members of the Sekigun-ha. One remained in their stolen getaway car with the engine running while the other three went inside clasping knives and a hunting rifle. “Quiet! Move and we shoot!” they shouted. They took ¥6 million in cash from the safe and then made good their escape. Unfortunately for the bandits the police were quickly alerted and the whole prefecture was locked down. One was picked up by a cop checking a train carriage, while a taxi firm’s tip led police to another of the criminals, armed at the time with a rifle, knife and homemade bomb. The final pair were caught the next day by Okayama Prefecture police at around three in the morning. The bank-robbing career of the Sekigun-ha was over.

The Left has an uneasy relationship with banditry and its practical role in revolutionary causes. While many have seen bandits as exemplar of dissent and rebellion — Bakunin and the Russian razboinik banditry, to name one — the line between criminal outlaw and political outlaw can be all too thin at times. Eric Hobsbawn is usually credited with starting the serious study of what he called social bandits, and what the JCP and Sekigun-ha did falls into his classification of “expropriation”: “the long-established and tactful name for robberies designed to supply revolutionaries with funds”.

Hobsbawn finds a convenient genesis for the phenomenon in the anarchist-terrorist milieu of Tsarist Russian in the 1860’s and 1870’s. However, the Bolsheviks were also “expropriators”, carrying out the infamous Tiflis (Tblilisi) hold-up in 1907 that gained the party 200,000 rubles in swag but also left forty people dead. In Bandits (1969) Hobsbawn goes on to give a portrait of the remarkable Spanish expropriator Francisco Sabate Llopart (1913-1960), a man who apparently only came into his own when he was in action with a gun. He had a long career of hold-ups, guerrilla raids, and daring escapes, but whose life eventually had an appropriately bellicose denouement.

The Symbionese Liberation Army (1973-74) were another example of leftist banditry. They sought the redistribution of wealth, though they differed from New Left groups in that they were not affiliated with a larger theory or movement, and also deviated from traditional bandits in that they had no links of community or kin. They were unattached individuals who came together in the East Bay. In this sense, they were pure counterculture, alienation extrapolated into action against the rich and powerful, in particular William Randolph Hearst.

Just as bandits feed on the mythology they inspire, so too do activists and dissidents strive for the propaganda benefits that their illegal actions foment. A difference lies in how while it was oral culture and ballads that established the legacy of outlaws, the radicals who borrowed the tactics of bandits were defined — for better or worse — by the mass media. This can make their repute and celebrity briefer than the likes of Jesse James et al.

It takes skill to politicize bank robbery. The Sekigun-ha had a brilliant name for their heist campaign, in the process bundling it up with their other esoteric Blanquist theories of revolution. They called the robberies the M-sakusen, the “M tactics” — the “M” stands for “mafia”, which is certainly apt.

Banditry plays with fire. When the revolutionaries have alienated the public, their careers will not go far. Spin-offs from the Weather Underground like the United Freedom Front and May 19th Communist Organization committed multiple robberies in the late 1970’s and early 1980’s. However it was a botched heist in October 1981 in New York that lingers most in the popular imagination. The so-called Brink’s robbery, executed by former Weathermen activists and members of the Black Liberation Army, saw a security guard murdered, along with two police officers who had the misfortune to stop the getaway truck containing the $1.6 million in loot. The arrests of many of the participants led to the obliteration of a network of safe houses and contacts, and the armed struggle of the American New Left was brought to an end by the mid-1980’s.

The Rote Armee Fraktion, though, in its first full manifesto, Das Konzept Stadtguerilla (The Concept of the Urban Guerrilla), penned by Ulrike Meinhof, claimed “we shoot only when someone shoots at us; the pig who lets us go, we let him go as well”. While the tract has been criticized for how it steers around the use of violence to liberate the RAF members a year prior, the group did seem to practise what it preached during the bank robberies it carried out in autumn 1970, when it stole 220,000 marks without firing a shot at anyone. The casualties that did arise were from shoot-outs with police.

Groups like J2M also went to special efforts to win over the common man, even giving chocolates to frightened bank customers during their robberies to reassure them. If the Sekigun-ha had tried this, how differently things may have turned out.

WILLIAM ANDREWS