When the Liberal Democratic Party wanted to produce an educational pamphlet earlier this year about its desire to change the Constitution of Japan, it chose a medium that many in the West might find surprising, even unbecoming, for such a serious subject: it published the pamphlet as a manga. However, for Japanese audiences, whichever side of the political spectrum they vote, there was arguably little out of the ordinary about such a choice. Politics and manga are far from mutually exclusive.

The Liberal Democratic Party’s manga about proposed constitutional changes

The characters discuss how “unfair” it is that other nations change their constitutions, but Japan doesn’t.

The tale of the so-called Yodogō Group — the members of Sekigun-ha (Red Army Faction) who carried out Japan’s first ever airplane hijacking in 1970 — is a strange one. The surviving hijackers, if they hadn’t tried to commandeer a JAL airplane and fly it to Cuba, would be collecting their pensions by now. Instead, they are stuck in limbo in North Korea, unable to return to Japan.

But even stranger than their lofty ambitions, perhaps, was their choice of language. When they announced their remarkable stunt, they finished off the grandiose proclamations of world revolution with a curious phrase: Ware ware wa ashita no jō de aru (We are Ashita no jō). This is a reference to a popular manga at the time and was the leftists’ way of communicating that they were the Everyman; at heart, they were just ordinary former college kids. And like the eponymous Joe, they were fighters.

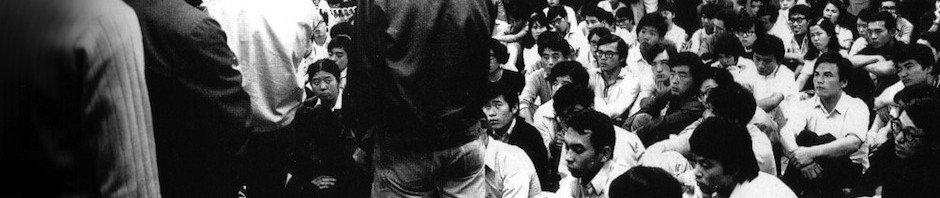

Ikki Kajiwara and Tetsuya Chiba’s Ashita no jō (Tomorrow’s Joe) (Kōdansha, Shūkan Shōnen Magazine) was serialised from 1968 to 1973, very neatly corresponding almost exactly to the height of the New Left protest cycle in Japan. It is possibly the archetypal manga of the period and certainly one of the most enduring in the popular conscious. The Japanese love underdogs and this manga is very much the story of one: a poor boxer fights his way to fame in the ring, only to meet a tragic end. Joe’s plight found a receptive audience in contemporary young readers, who saw themselves likewise struggling against the system. Student activists revered martyrs like Hiroaki Yamazaki, a Kyoto University student who died in 1967 while participating in a violent protest at Haneda Airport against Prime Minister Eisaku Satō’s trip to Asia. Joe dies too, a lonely rebel who gives it his all. It isn’t hard to see why his story appealed.

Manga was popular for the generation who produced the Zenkyōtō movement, Japan’s campus strikes and struggles that reached a peak in 1968-69. This article will examine the depiction of New Left incidents and movements in manga through three case studies. During the 1960s manga provided poor male students in Japan with cheap entertainment. TV sets were much sought after at that time but the lives of most students in Tokyo and other cities were too impoverished to join in the consumer revolution. Into this vacuum poured student clubs and activism on and off campus.

Japan’s defeat in 1945 had offered it an opportunity to start again as the Switzerland of Asia: neutral, peaceful, and cultured. However, during the American occupation it quickly became apparent that Japan was being positioned firmly into the Western camp. The emperor system was left in place and many of the people associated with the pre-war regime remained in power. For those on the Left, Japan’s troubling imperial past was over in name only — its legacy was not expunged or reconciled. A sharp rise in unionism and industrial strife promised to come to a head with a general strike in 1947, but this was aborted at the last moment. The terms of the peace treaty with America also saddled Japan with large numbers of foreign military bases up and down the country, including some very close to major cities like Tokyo.

Zengakuren, the national league of student councils, was founded in 1948 and became the driving force for militant student activism when control over the councils was seized by an ultra-left faction opposed to the Japanese Communist Party, after it had started to segue into a fully mainstream political entity from around 1955. While there were also labour groups, the emerging New Left factions recruited the bulk of their cadres from student bodies through affiliations with certain student councils at campuses around the country. This meant the increasing numbers of factions were well stocked with passionate youngsters, though the worsening division of the New Left also resulted in violent infighting.

The first major mass campaign for the New Left factions was the struggle against the renewal of the Anpo security treaty between Japan and the United States in 1960, which also involved millions of ordinary citizens and unionists. Following this, the groups also protested the normalisation of relations between the Republic of Korea and Japan in 1965. Meanwhile, demonstrations against the U.S. military bases located around Japan had been continuing since the 1950s, as well as against the dockings of nuclear-powered submarines. But when the American involvement in the Vietnam War began — and by extension, Japan’s, since U.S. bases in mainland Japan and Okinawa were heavily utilised — the protests intensified.

The issues of Okinawa and the terms of its belated return to Japanese sovereignty, as well as the 1970 Anpo renewal, all merged into ideology of the New Left, which conflated the campaigns as part of the overall anti-war and anti-capitalism cause. The localised campus struggles, such as famously at Nihon University, Waseda University and the University of Tokyo, were also contextualised by participants as part of these broader campaigns. In their minds, all the campus strikes were joined together into a national movement, since the universities were representatives of the Establishment, imperialism and capitalism.

The first weekly manga magazine, Shūkan Shōnen Magazine, was launched by Kōdansha in 1959, the year the protests against the first Anpo renewal began. Readership rapidly expanded and by 1966 it had a circulation of one million. In the late 1950s the populations of the cities had been swelled by migrants from the rural regions. Like college students, these poor male factory workers relied on cheap manga for their entertainment. Around this time, “manga” was primarily content expressed in a cute style, published in monthly magazines aimed at children or younger readers. An alternative industry existed in the form of the akabon “red books”, which were produced mainly in the Osaka area and distributed through manga rental libraries. The likes of Osamu Tezuka had already achieved immense success with the akabon format by the later 1940s.

In the post-war period two discrete but ultimately symbiotic trends emerged: the development of more serious, realistic styles of comics, as opposed to the prevalent style of children’s manga; and the development of new formats, such as the yokabon manga booklets and, eventually, the weekly magazines. In 1957 the term gekiga was coined, meaning “dramatic picture” and referring to comics with a more highbrow artistic style, typified by the work of Sanpei Shirato and Shigeru Mizuki.

The rental manga outlets flourished as single books were still expensive. However, everything changed with the arrival of the cheap weekly magazines launched by mainstream publishers like Kōdansha and Shōgakukan, which also intersected with the debut of many weekly magazines in Japan in the late 1950s and early 1960s, including Asahi Journal. The Baby Boomer generation was reaching their early teenage years at this point and their elders expected them to put aside their “childish” comic books. Instead, the weekly magazines meant that a range of content was now affordable to youngsters.(1) Although content for children still prevailed, by the late 1960s commercial publishers were regularly serialising manga dealing with adult and social themes, including Shūkan Shōnen Magazine. For example, Akuma-kun (Little Devil) (Kōdansha, 1966-67) was ostensibly a supernatural fantasy comic but also embedded with anti-war messages.

The previously antagonistic styles of gekiga and mainstream “manga” — i.e., a medium for children — converged when the gekiga leaders started contributing to the weekly magazines. Shirato’s work featured in Shūkan Shōnen Magazine in 1960 and Mizuki’s in 1965.(2) Eventually, though, Shirato would seek out editorial independence for his politicized historical visions and he chose to publish the first series of Kamui-den (The Legend of Kamui) (1964-71) in the monthly magazine Garo when it launched. Garo served as an exciting counterpart to the weekly magazines throughout the decade with anti-establishment storylines. After Shirato left in 1971 its sales dwindled, though it remained a vibrant fringe publication and part of the 1970s avant-garde.(3)

Since the Baby Boomers had grown up reading the output of Osamu Tezuka, the manga readership became more sophisticated as the generation itself matured. Manga became a format that allowed for a certain amount of subterfuge; the willing writer could sneak in political messages into “entertainment”. As such, as society was experiencing seismic shifts, even a populist medium like manga reflected this willingly. There was an increase in political themes in the 1960s, as Sharon Kinsella has previously discussed. Manga were published portraying the Buraku lower caste, poverty, class oppression and other urgent social issues. Fujiko Fujio, most famous for Doraemon (Shōgakukan, 1969-96), even wrote a manga about Chairman Mao.(4) The storylines in Sazae-san (Asashi Shimbun, et al., 1946-74), the seemingly innocuous manga by Machiko Hasegawa about family life, featured social themes almost 30% of the time in 1970.(5) Several top manga artists also found pockets in their busy publishing schedules to illustrate union pamphlets in 1969, at the height of the campaign against the renewal of the Anpo security treaty in 1970.(6)

Manga-ka had varying reasons for tackling these subject matters. Some, such as Shirota, were Marxist fellow travellers and built a career around their political stance. Others, such as Mizuki and Tezuka, were inspired directly by their own wartime traumas. The former contracted malaria and lost an arm while serving as a conscript in the Imperial Army. He fused his personal wartime experiences into his work, most notably Shōwa-shi (The History of Shōwa) (Kōdansha, 1988-89), a non-fiction manga memoir that does not shy away from depicting Japanese war crimes. Mizuki’s courage to introduce these themes into a mainstream manga project is even more impressive when we consider that it was first published on the eve of the Shōwa Emperor’s death, a highly sensitive time in Japanese society. Although best known for his endearing, ostensibly anodyne comics, Tezuka’s witnessing of the horrific bombing of Osaka deeply affected him and his work. The autobiographical manga Kami no toride (The Paper Fortress) (Shōnen-gahosha, Shūkan Shōnen King, 1974) dealt with the firebombing, while during the 1950s he published several manga critiquing nuclear arms — to name just some of the many politically toned manga he wrote during his long career.

The central government was noticing these developments and blacklisted certain manga it accused of inciting violence, including Ashita no jō. In 1967 it established an agency for monitoring manga, the Seishōnen Taisaku Honbu (Youth Policing Unit), within what was then the Sōmuchō (Management and Coordination Agency), and genuinely seemed to fear the influence the drawn cells might have on radicalised students. Based on manga reported as “harmful” in each prefecture, the censors print a quarterly list of manga for distribution to publishers, libraries and news media. Of course, it wasn’t just violent and leftist manga that unnerved the authorities; erotic comics were also regularly included on the official codex of toxic literature, and remain hounded today. However, the actual power to “ban” manga rests with local governments, limiting the effectiveness of the unit, though it did in the short term contribute to the growing debate about gekiga violence.(7)

Sakura-gahō (Sakura Illustrated)

Sakura-gahō (Sakura Illustrated) is by far the most original work discussed in this article and places its author, the late Genpei Akasegawa, in the great tradition of political cartoonists. When Akasegawa died in late 2014 commentators and obituarists were quick to point to his contributions to Japanese post-war anti-art. Indeed he did have the unusual distinction of having been a member of two of the most important groups from the time, Neo Dada and Hi-Red Center, not to mention playing a role at the centre of the greatest cause célèbre in post-war Japanese art until Nagisa Ōshima’s obscenity trial over In the Realm of the Senses. In between the controversy and buzz that Akasegawa generated, it is easy to forget his prolific manga output.

“Manga” here means something very different to the weekly offerings of Shūkan Shōnen Magazine, et al. Akasegawa belonged to the counterculture and avant-garde art movement that was immensely fertile during the post-war period, and as such his “manga” occupies very discrete territory to the regular entertainment titles being published at the time, although he was fortunate to find a very mainstream channel to serialise his work. “Manga” is a word with myriad implications and a subversive and irreverent figure like Akasegawa reminds us that the first character has connotations of the morally corrupt: “manga” can mean “irresponsible pictures”.(8)

His manga is much closer to the kind of political cartoons that are a staple of satire in the West — more Charlie Hebdo than Ashita no jō. That being said, Akasegawa’s comics are not political in the overt sense like the newspaper cartoons of European or American broadsheets. He did not depict and caricature politicians per se, though he was directly involved in the New Left movements of his time. He illustrated a poster for the propaganda film Red Army/PFLP: Declaration of World War (1971), which was essentially a recruitment film for what later became the Japanese Red Army, as well the cover for Narazumono bōryoku senden (Rogue Violence Propaganda), a 1971 anthology of the leftist firebrand Osamu Takita’s writings. Akasegawa’s palette was very much filled with red paint.

Genpei Akasegawa’s brilliantly satirical, visionary Sakura-gahō

Sakura-gahō (Sakura Illustrated) eschews narrative logic for visual flair and caustic sting. The title deliberately stakes a claim on respectability, employing the more difficult Kanji character for sakura (cherry blossom) and with the gahō recalling the names of established publications like Fujin-gahō.

Akasegawa’s manga was serialised in the now defunct Asahi Journal in 1970-71 at the height of Akasegawa’s notoriety. Asahi Journal was a leftist staple, just like manga. “In the right hand, Asahi Journal. In the left hand, Shūkan Shōnen Magazine,” as the Waseda student newspaper put it in 1970. Surely this marriage of two favourites of the Left would be a match made in heaven? Akasegawa was not actually the first manga artist to be published in the Journal, though his contribution certainly generated publicity for the magazine — ultimately for the wrong reasons.

Sakura-gahō appeared over three pages inside the weekly Asahi Journal but Akasegawa brazenly gave his modest section its own masthead and issue number. There were fake adverts included on the “back page”, plus numerous other details all conspiring to suggest that Sakura-gahō was its very own magazine, Asahi Journal merely “subtracted” to distribute it to the public. Asahi Journal was simply the wrapping, what the Japanese magazine world today calls the omake, the free giveaway that comes with an issue. This was typical of Akasegawa to send up form and simultaneously bite the very hand that was feeding him. Sakura-gahō even imitated the parent publication supporting the author’s livelihood, the typography and cherry tree background logo clearly a cod version of Asahi Shimbun’s.

The title page also ran a grandiose triptych of slogans under the date:

Sakura, the king of flowers and the national flower

Sakura, a humble meat and an onlooker

Sakura, a spectator and a conspirator

As we would expect from an anti-art pioneer, Akasegawa is debasing the format he is using. From the very first page the reader knows that nothing will be taken seriously and yet, the author’s targets are serious enough: the nation state itself. In gekiga graphic style, Akasegawa depicts — at times directly, at others more obliquely — pressing contemporary topics such as the Sanrizuka protests against Narita International Airport, police brutality, and Yukio Mishima’s quasi-coup.

From the twenty-third issue in January 1971 he introduced two recurring characters and a semi-narrative. The “Hana-arashi” (flower storm, meaning a wind blowing petals) series centred on a horse and a young boy. The former was a pun on yajiuma, the word for onlooker or bystander that includes the Kanji character for “horse” (hence the joke in the title about an onlooker being “humble meat”). In fact, Sakura-gahō had first been titled Yajiuma-gahō and horses were a constant motif in the previous issues. Akasegawa was writing about the nation of onlookers now paying witness to social tumult and the Japanese government’s complicity in Vietnam; he was pointing the finger at the public. Now the horse motif has become Uma-ojisan (Old Man Horse) and his companion is Sohei Kozō, whose name implies a young apprentice traveling monk but, in his hachimaki headband and black uniform, looks like a mini Yukio Mishima wannabe.

Uma-ojisan and Sohei Kozō are so bored they make a storm with their snot, which blows to the police, who then analyse the petals/snot of these “onlookers”. The snot eventually builds and builds, crushing the riot police. Finally, there is so much snot that it explodes.

Sakura-gahō makes for a very timely read today. The “Special Issue” in August 1971 is all about growing militarism. Outside the Diet the air is filled the sounds of marching soldiers, only they are multiple pairs of Uma-ojisan and Sohei Kozō. Crowds gather to watch; volunteers join up to this new army of “sakura soldiers”. The weapons industry flourishes. “All power to the army of onlookers,” a sign declares. The military grows into the mightiest in Asia:

A rifle at every table.

A bazooka at every bedside!

A hydrogen bomb in every home

“Stupid, not so much,” notes our horse narrator drily. We are all part of the army precisely because we are only onlookers. Not to do something is the same as being conscripted into the state’s army. Akasegawa was writing at a time of increased riot police violence against students and activists, as well as intense social disturbance from the New Left agitators. 1971, in particular, witnessed a lot of bombings: 62 explosives were recorded by police, 37 of which actually went off, resulting in dozens of casualties.(9)

But satire can go too far and result in a slap on the hand. Asahi Journal recalled the current issue in March 1971, after which it wasn’t published for two weeks. Why? In the words of one contemporary, “media freaking” over Sakura-gahō.(10)

The problems came with the thirty-first instalment in March, which carried “an important announcement” where the horse and boy said they were heading on to look for a new place to “hijack”. The Asahi logo was seen rising up as the dawn sun (asahi means “morning sun”) and the words “Red Red Asahi Asahi”. Again, Akasegawa was mocking the “left-wing” Asahi for not being up to the task and his choice of phrase mimicked a wartime textbook. “If the Asahi is not red, it’s not the Asahi,” a pun-filled caption reads. The yajiuma are now “soldiers” on the look out for their next target to hijack. (Akasegawa provocatively made ample use of this word, nottoru — hijack — not long after the Yodogō incident.) We can only speculate what the next instalment would have been. The whole issue was recalled, the editorial staff changed and the serialisation of Sakura-gahō came to an end. We should not exaggerate: the cover of the Asahi Journal that week had also featured a nude, which caused trouble in its own right.

Akasegawa was no stranger to scandal. He had only just come out of a long trial over accusations of “imitating” money. The obviously fake bills that he used in artworks caused him to be charged under an 1895 law against “copying” money (as opposed to actual counterfeiting). In 1964, upon being fingered for the crime, he defined his practice as “shit realism — not socialist but capitalist realism”. In his “Capitalist Realism” manifesto he declared “real things… are not easily observed”.(11) He was interested in the act of observation, in looking at a crime. He performed his counterfeit through an acute process of observation. He was not the criminal; he was “observing the criminal”. The final ruling came in 1970. Akasegawa typically turned the whole legal process into an art project — appropriately, since the trial was about the very freedom of artistic expression — and kept up his ludic experiments with the motif of fake money until 1974.

In the same way, neither did the Asahi Journal fiasco deter him. He continued to draw ad hoc satirical graphic design and manga during the 1970s. He revived Sakura-gahō in Garo (heavily associated with leftist politics) and elsewhere in 1971. Sakura-gahō was made available as a collected volume in 1971, again in 1977 and then in paperback in 1985, complete with supplementary texts and the English-language version of the Special Issue.

This had already been published in Concerned Theatre Japan in August 1971. The same issue also ran a translation of a manga by Sanpei Shirato, who is famous for his politicised historical comics. (The Concerned Theatre Japan editor, performing arts scholar David G. Goodman, has suggested that the issue constituted the first full-length English translations of modern manga.[12]) While little has been written about Sakura-gahō in English and it remains relatively obscure today, it was featured in the “Roppongi Crossing 2013: Out of Doubt” exhibition at Mori Art Museum (21 September 2013 – 13 January 2014).

Ever the cheeky provocateur, Akasegawa proclaimed his own state, the “Genpei Akasegawa Capitalist Republic”, in the foreword to a 1974 edition of Sakura-gahō (“currently the state territory is just my physical body” existing in his apartment in Nerima ward, Tokyo). The nail that sticks up gets hammered down, as the Japanese adage goes, or, in Akasegawa’s case, you can just stick your tongue out. “In this state all manner of criminal, revolutionary and bystander-esque expressions are designated national treasures.”(13)

Akasegawa’s subsequent career was as varied and unexpected as you’d imagine from such a troublemaker and innovator. He wrote screenplays for director Hiroshi Teshigahara and award-winning novels and short stories, as well as founding Rōjō Kansatsu Gakkai (Street Observation Academy) in 1986, along with the likes of architect Terunobu Fujimori. This group conducted Situationist-style investigations into the city space, training their gaze on unusual sites, strange objects, and quirky scenes. This was then outputted as photographs and printed materials. These activities were showcased at Fujimori’s Japan Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2006 and at a Fujimori retrospective at Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery in 2007.

Boku no mura no hanashi (The Story of My Village)

Horses are also a central motif in Boku no mura no hanashi (The Story of My Village) by Akira Oze, a manga-ka probably most famous for Natsuko no sake (Natsuko’s Sake) (Kōdansha, Weekly Morning, 1988-91). Boku no mura no hanashi was serialised in Weekly Morning magazine from 1992 to 1993, and then published as seven paperback single volumes (tankōbon) between 1992 and 1994. Now out of print except for a Kindle edition, it tells the story of the Oshizaka family and their involvement in the protests against the construction of a new international airport in the area where they live. It is, of course, meant to be about the intense campaign by farmers and activists in opposition to the proposed plan to build Narita Airport in Sanrizuka, a struggle which continues even today and ultimately resulted in several deaths.

The protest against Narita Airport’s construction involved both Old and New Left groups, though the latter saw the project as much more than just a trampling of rural residents’ rights. The airport was a potentially major conduit for the American war machine and Japan’s own complicity in it at the height of the conflict in Vietnam. Protesting the airport was fighting the state and militarism.

Oze’s manga fits in with a trend in comics during the 1990s to turn to more turbulent times for inspiration. Kinsella calls this a nostalgia caused by the downturn witnessed in manga content in the period, when the major manga publications were issuing mostly dull or apathetic works. The contemporary manga-ka seemed to have little to write about in early Heisei-era Japan; good manga is linked to unstable times when there are always urgent themes begging out to be used.(14) Oze’s manga was joined by Medusa (Shōgakukan, Big Comic, 1990-94) by Kaiji Kawaguchi, which deals with the Japanese Red Army and whose main character is modelled after Fusako Shigenobu.

Boku no mura no hanashi also arrived at the same time as a surge in the anti-emperor protest movement during the period of changeover between the Shōwa and Heisei emperors, as well as renewed bombings and other incidents connected to the Narita Airport protest movement. Although the airport had been open since 1978, the controversy surrounding it was still very much in the public eye. In an afterword, Oze explicitly connects his manga to a symposium in 1991, the first such formal dialogue between the airport authority and the protest group faction led by Hajime Atsuta. Attending the event was instrumental in shaping Oze’s vision for his manga. The 1990s saw further conciliations and negotiations between the two sides, though some protestors have continued their struggle against the airport to the present day.

Boku no mura no hanashi by Akira Oze

At the start of Oze’s manga, the Oshizaka family are living an idyllic life in the Chiba countryside. It is a place of fields, children and sunsets. A nearby pasture is home to beautiful horses and the kids hunt for a legendary white stead, which, needless to say, makes beguiling appearances at transcendent moments. Oze’s imagery is not subtle. He clearly sets up the rural paradise for a crash, which arrives with the announcement of the newly changed construction plans, taking the airport site directly onto the land occupied by the family and their fellow villagers.

The manga has the tone and scale of seinen manga (marketed to young men in their late teens or older), though its choice of male central character seems to locate it in the genre of shōnen manga (marketed to adolescent boys). This is a rite-of-passage tale, with the young Teppei at its centre and the rest of his family, plus the other sections of the local community involved in the protest movement.

Readers with a keen historical eye will spot the slight changes in the names of many characters and places. “Narita” becomes “Shigeta” (using similar Kanji); “Sanrizuka” becomes “Sannozuka”, and so on. The attempts to mask the true-life models for the story are only half-hearted. Even the horses and the pasture are based on an actual one then owned by the Imperial Family in the Sanrizuka area. There are also frequent references to the period setting, from the Beatles to the 1964 Olympics and the 1970 Osaka Expo. The TV is still a new and life-giving presence in the family home, something which mesmerises young and old as a fountain of information and entertainment.

The manga is a blow-by-blow chronicle of the Narita affair from 1966 to 1993, portraying how the site was decided by the Airport Authority without consulting the locals and how it became a rallying call for outside student activists to pour in and assist the farmers in their struggle. Oze shows the conflict among families caused by the anguish of whether or not to accept the generous compensation offered by the Airport Authority, or whether to fight against the airport on sheer principle. While the police are for the most part mere columns of uniformed riot cops, sinister rows of marshal figures inflicting pain on the outnumbered locals, Oze does make his story relatively panoramic. On top of the farmers, we see the perspectives of teachers, contractors and students.

Teppei’s older brother, Hiroshi, is initially a hackneyed wayward son character but the airport protest becomes the springboard for mending his relationship with his father. In turn, he gets deeply involved in the movement, as does Teppei. The young boy goes from eavesdropping on the grown-ups’ conversations about the airport to joining the youth corps and actively campaigning in spite of his age.

As the long, arduous battle against the authorities escalates, resulting in arrests and bloodshed, Teppei matures and learns. He starts off frustrated at his powerlessness, constantly told that the “airport is the business of the grown-ups”. Nonetheless he perseveres in his nascent activism. But when one of his early attempts to help the protest backfires due to how it is covered by the media, his response is telling: “I won, but I still lost.” This ambiguity could perhaps also stand in for the entire Sanrizuka campaign — the farmers and their leftist activist allies fought tooth and claw, delaying the airport massively, but their defeat was inevitable.

The finale is a depressing one, as it should be: a rain-drenched clash during the first land expropriations in 1971. Just as in real life, the conflict left three riot police officers dead and Hiroshi is one of the many young activists arrested. He faces a long trial to clear his name. One of the activists commits suicide — again, based on a true event — and the manga ends on a note of failure.

Oze’s manga is about Narita and it is certainly partisan (he credits Hantai Dōmei, the airport protest league, with research help). It is also about an earnest young boy growing up and a family experiencing wrenching trauma, as well as a rural community. But ultimately he is writing about two broader themes. By continually use the word hyakushō (peasant, or farmer) in dialogue he reminds readers of history — that the Narita protest can be placed in the context of pre-Meiji peasant uprisings, which too were typically triggered by issues of unfair local taxation or duress. Oze’s subject is the Japanese village and how throughout history it has been oppressed by greater outside forces. And his second subject is democracy itself. “Is democracy not a courtesy?” as Oze asks on the very first page of the manga. No such democratic decorum was shown to the farmers in his story, or to the real-life farmers of Sanrizuka.

Red 1969-1972

In the same way that the 1990s saw a wave of nostalgia for past days of activism, so too did the 2000s experience a serious revival in interest in recent New Left history. This took the form of several films about the Rengō Sekigun (United Red Army), as well as numerous books and events. And it was within this vogue that Naoki Yamamoto came along with Red 1969-1972.

The successful manga was first serialised in Kōdansha’s Evening and then as collected single paperback volumes from 2007. The eighth and final volume was published last year. These large, attractive editions have sold well; the first volume alone was reprinted at least nine times. It also won an Excellence Award in the Manga Division of the 14th Japan Media Arts Festival in 2010, organised by the Agency for Cultural Affairs. To date, it is perhaps the most famous mainstream dramatisation of Japanese radicalism, which has inspired surprisingly few films or works of fiction considering the scale of the movement in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Sekigun-ha (Red Army Faction) was formed in 1969 as a breakaway from another New Left group. The campus strikes were still going strong and the struggles against Narita, the Vietnam War, Anpo, and the situation in Okinawa were all at their height. While their fellow activists were already violently clashing with riot police on the streets of Tokyo and elsewhere on a regular basis, the 300 or so initial members of Sekigun-ha hoped to kick-start revolution through spectacular agitation and incidents. This led to sporadic, but ineffective guerrilla attacks on police facilities in Tokyo and Osaka in late 1969. The Sekigun-ha vision was also highly internationalist, more so than other New Left groups; they saw their crusade as very much part of a global series of revolutionary struggles. This worldview inspired certain members of the faction to hijack a plane in 1970 and others like Fusako Shigenobu to go to the Middle East.

As its name suggests, Red 1969-1972 charts the involvement of certain members of Sekigun-ha and Kakumei Saha (Revolutionary Left), first in campus activism, growing increasingly violent and militant during 1969 and 1970, leading up to the factions’ merger as Rengō Sekigun in mid-1971. Through his ensemble Yamamoto chronicles the characters’ participation in the street protests that turned into riots, and then incidents such as the gun shop robbery that yielded the Kakumei Saha an arsenal of weapons. While ensconced at a mountain base in late 1971, the newly formed Rengō Sekigun descended into a horrific purge of its own members. A handful of the survivors then held the police at bay for several days in February 1972 inside a lodge in Karuizawa, an event known as the Asama-sansō Incident.

Red is presented as a “story of young people who aimed for revolution” — as if this very concept is so alien to millennials that it requires explanation as a premise (though ironically, given the protest activities of groups like SEALDs in 2015, this is possibly less the case today than when first published). Unlike Oze, Yamamoto’s manga has more pretences of dramatised non-fiction and hardly hides the source. But whereas Oze starts with a tone of the rural idyll before it is destroyed, Yamamoto opts for tragedy from the start. The first page double-page spread shows the dramatis personae in colour with numbers (later corresponding to the characters when introduced in the comic so the reader can keep track) and downcast faces and closed eyes (an image also on front and back cover). The opening page of the first volume is a quasi-news image of the final clash in the University of Tokyo campus strike in January 1969 with commentary. The back pages feature detailed information on other events and a timeline of the period. Yamamoto gives the semblance of researched accuracy, but also fatalism.

Naoki Yamamoto’s Red portrays actual incidents

Note the use of “redacted” names to give the manga a factual feel.

Actual character names and the names of the factions at the centre of the tale are changed from the real-life models. However, other names like “Asama-sansō” are instead blacked out (“XXX-sansō”), implying it is a real incident or place, with the actual printing of the name redacted for legal convenience. In this way, the manga is framed as fictionalised history, rather than historical fiction. Stylistically this contrasts to Kōji Wakamatsu’s 2008 film about Rengō Sekigun, which deliberately jumps between documentary, narrated commentary, and straightforward dramatisation to create a Brechtian distancing effect. This reminds the viewer of the reality of the events on screen while also maintaining a remove to avoid the inevitable glamorisation of celluloid (see Carlos, The Baader Meinhof Complex, inter alia).

There is a palpable atmosphere of impending doom from the start. Not only does this work well as a dramatic effect, it also makes logical sense for today’s digital generation of readers, who will surely be googling things as they go along, assuming they are even ignorant of the ultimate fate of the Rengō Sekigun members. To pretend that you can keep them in the dark until your final climax is naive when dealing with such a famous subject matter; it is far better to use this pre-knowledge to your artistic advantage.

A character chart at the back lists the characters and their mutual connections, including details of their final sentences and countdowns to how many days they have left at this point in the manga until their respective arrests and sentencing. Likewise, each chapter is framed chronologically (“February-March 1970,” etc.), heightening the sensation of both the story being factional and that the events are happening on a path toward ultimate disaster. At various moments in the narrative, text in the cells tells the reader of the fate of the characters at dramatic moments, hammering home the futility and self-destruction of the movement. In this way, it replicates the myth that the Rengō Sekigun self-destruction in 1972 destroyed a generation of activism, an interpretation almost universally echoed today. However, as major left-wing campaigns such as the struggle against Narita Airport continued on a mass scale until well into the 1980s, we should treat such simplifications with a degree of caution.

The art style is highly graphic and technically impressive. Yamamoto also writes under different pen names and is active in erotic manga genres; one of his efforts was placed on the government list of “harmful” manga in 1992.(15) Not surprisingly, Red is laced with violence and eroticism, which arguably amounts to a glamorised portrayal of the theme. Does this slide into sensationalism? This is always the difficult line for writers and artists to tread. There are certainly moments when Yamamoto and his editors did apparently aim for the lowest common denominator. The advert for the second volume at the first back of the first page features several close-ups from a bedroom scene. The copy reads: “Revolution. Struggle. Sex. The peak of the young accelerates.”

A sequel, covering the “final 60 days and Asama-sansō,” has been serialised in Evening since 2014, with the first paperback volume published in February 2015. The follow-up goes over the incidents from the purge in the mountains, followed by the police siege. It is a faithful dramatisation and does not spare the violence. Every brutal punch is featured in close-up.

The details of the purge depicted in the second manga will be familiar to anyone who has read the many memoirs of the participants, which were actually published mostly in the 1980s and 1990s, or the more recent retrospective summaries that have come out in the past fifteen years, especially Eiji Oguma’s monumental two-volume 1968 (Shinyōsha, 2009) and Wakamatsu’s film.

In the context of post-Fukushima Japan, it is tempting to see Red as a timely reassessment of earlier politicised youth movements, though it actually belongs within this post-2000 movement of literature and commentary looking back to the 1960s and early 1970s, which resulted in numerous books, films, art exhibitions, and more — many of them organised by people from a younger generation.

While actual contemporaries like Hidemi Suga published scholarly works examining the legacy of Zenkyōtō, others like Eiji Oguma instead attempted to collate mountains of resources into a new assessment and summary suitable for a new age. In 1968, Oguma presents no original interviews with participants, instead relying on archive materials. His achievement is considerable but he was criticised for his methodology. Current film students from Nihon University organised a Zenkyōtō-themed film festival at Euro Space in Shibuya in 2011, working with original veterans from their college’s campus strike. Many of the films screened were incredibly rare. In 2014, another rare film, featuring raw footage from the so-called “folk guerrilla” rallies at Shinjuku Station’s West Plaza in 1969, was published along with a book including a series of articles and interviews with participants. In this way, the past was being rediscovered both for a new generation and anew by the original participants themselves.

Red fits into this milieu but is far more dramatised and populist; it isn’t collating, it is re-enacting. Its occasionally sensationalised approach to the subject makes its interpretation of the recent past more troubling. Yamamoto’s personal politics aside, this is a slick portrayal of history with high production values. The art is skilfully rendered, which only heightens the impression that the theme is being treated as pure drama. In this respect, it is perhaps closer to the film Totsunyū seyo! Asama-sansō jiken (2002), which shows the Asama-sansō incident from the police perspective, than Wakamatsu’s more episodic film adaptation. For example, when Oguma set out to make a documentary film about the anti-nuclear power movement, of which he has been an outspoken evangelist, his technique is revealing: he used only “found footage” of the demonstrations, shot by other people in the months after the Fukushima disaster, and edited them together into a final film that was released in 2015.

In Red, there is arguably no overt critique of what happened beyond the realistic depiction of militant activism, nor is Yamamoto being truly nostalgic — the “drama” is too intensely depicted for that. The aforementioned period framing devices Yamamoto uses are clever tricks that add a sense of fatalism and hindsight to his tale, but are ultimately narrative devices commonly employed, especially in fiction, film and TV drama. In this way, we seem to have finally arrived at a point when, while many of the participants are still alive, there is nonetheless enough distance from events and ideology to produce a non-partisan, purely artistic “story of young people who aimed for revolution”.

As the manga continues to be published in present-day Japan, during the second administration of Shinzō Abe, it is interesting to place its portrayal of violent, impassioned youthful “extremism” next to the political movements that have emerged during the Heisei Period. What is commonly called freeter activism is generally characterised by an anarchistic but positive tone, and with a strong presence of musical elements, most notably “sound demos” — marches led by vehicles and floats equipped with a DJ booth, speakers and musicians. This new spirit of energetic but non-violent activism gained prominence with May Day protests in the mid-2000s and the anti-war protests during the Second Iraq War, though there had been plenty of earlier examples in the 1990s. The 2009-11 protests over the redevelopment of Miyashita Park in Shibuya — used by many homeless — as a partnership between Nike and the local ward government saw the participation of artists and activists in a playful, yet sincere way quite distinct from the New Left activism in previous decades. The demonstrators squatted in the park, held a festival, and marched on a Nike store in colourful costumes. Spearheaded by groups such as Shirōto no Ran (Amateurs’ Riot) in Kōenji, this new protest movement also fused with the anti-nuclear power protests that exploded in 2011-13 and the recent security bills protests (2014-15). Led by photogenic groups like SEALDs (Students Emergency Action for Liberal Democracy-s), protest has once again become hip and glamorous, and generated reams of media interest. But in contrast to the forthright, militant New Left radicals, the core SEALDs activists are famously polite, deferential and careful about their relationship with the police. It is also very unlikely that such a nonsectarian student group as SEALDs even knows much about the events depicted in Red, or has read the same political tracts as the Sekigun-ha activists had. Ironically, given the distance of time involved, perhaps their first point of contact with this recent history would in fact be Yamamoto’s manga.

Conclusion

It goes without saying that politically themed manga is alive and kicking today, as just a cursory examination of recent publications reveals. Numerous manga have dealt with Fukushima, nuclear power and the 2011 tsunami. And as the controversy over the portrayal of Fukushima in long-running food manga Oishinbo (Shōgakukan, Big Comic Spirits, 1983-ongoing) last year demonstrated, comic book depictions of political subjects still have the potential to generate front-page news.

Note the use of manga-like illustrations in this flyer for an anti-nuclear power protest on March 11th, 2015.

Part of a flyer for the August 30th, 2015 Sōgakari protest rally against the security bills.

Literature produced by the office of liberal independent politician Tarō Yamamoto

From a flyer advertising a human chain protest around the Diet in protest at the development of Henoko Bay in Okinawa for a US military base

Even in New Left campaign literature today, while the slogans and vocabulary may be bold and aggressive, it is common to see pamphlets with illustrations and “cute” decorative flourishes (see above for examples from the far and centre Left). On the Right too, manga serves as a tool for communication and propaganda. No discussion on this can exclude heavyweight Yoshinori Kobayashi , whose meta-manga series Gōmanizumu sengen (The Arrogance Manifesto, a riff on The Communist Manifesto) (various publications, 1992-ongoing) features the author expounding on issues like the Nanking Massacre, whaling, comfort women, AIDS, and basically anything else that falls into the ambit of Kobayashi’s current agenda. While often categorised as a right-wing or ultra-nationalist figure, Kobayashi’s politics are hard to pin down exactly, since he has also railed against the present government, discrimination and even nuclear power (on the whole, all issues within the agenda of the Left in Japan). In many ways, he is as much an anti-establishment provocateur as, say, Akasegawa.

Even the cult Aum had its own manga. The misspelling of “Armageddon” comes from the Japanese pronunciation.

As Sharon Kinsella has explored, manga includes a disproportionate presence of people with strong political views and a chip on their shoulder against society. Many of the people who ran small erotic or subcultural publications arrived at their vocations after participating in activism, dropping out (or when the faction collapsed, as was frequently the case), and then having scuppered their chances of a “normal” career in the corporate world: “Counterculture and subculture was driven by ex-radicals, and this included manga.”(16)

This links to a later form of subculture that has recently lost its “counter” sheen. Today the otaku is largely accepted by the mainstream. Otaku idol culture is embraced by television and music, and even celebrated by the government-initiated “Cool Japan” campaign as part of the image Japan Inc. should exploit to sell itself. But before there was soft power, the otaku was a renegade, a dangerous dropout from society. His mercurial rise is connected to the disillusionment of the New Left radicals. Cultural critic and thinker Hiroki Azuma suggests the emergence of otaku is a byproduct of the 1970s, the period where political activism declined and Japan experienced several social jolts (the Oil Crisis, the Rengō Sekigun incident). “We can view the otaku’s neurotic construction of ‘shells of themselves’ out of materials from junk subcultures as a behavior pattern that arose to fill the void form the loss of grand narrative,” Azuma says.(17) Given the ubiquity of otaku anime and manga tropes today, we can conclude that the void was successfully filled, though perhaps the disillusionment with grand narratives is irreparable. “For the first-generation otaku who appeared [during the 1970s], knowledge of comics and anime or fan activities played a role extremely similar to the role played by the leftist thought and activism for [the previous] generation [of student activists].”(18) Activists are geeks, and geeks are activists.

Certain student activists in Japan today use a lot of anime motifs in their publicity and social media presence. This is the Twitter account associated with the far-left Hōsei University activist group Bunka Renmei.

At times, the use of anime images is inventive and entertaining. This is a tweet celebrating the release of fellow activists.

And so perhaps the next area awaiting investigation is the relationship between anime and New Left activists today. If the student activists of the 1960s grew up reading manga, then the younger activists in Japan in the present have backgrounds in anime. This is clearly ingrained, since for them it seems to sit easily with aggrandised proclamations against neoliberalism, capitalism and so on. The left-wing activists engaged in a lengthy ongoing dispute with the private college Hōsei University, for example, frequently employ anime screen captures and other moe character motifs in their social media channels to illustrate their messages. In the end, pop culture, subculture and counterculture all exist in symbiosis.

References:

Concerned Theatre Japan (Volume One, Number Three) (1970)

Concerned Theatre Japan (Volume Two, Number Two) (1971)

Genpei Akasegawa, Sakura-gahō: Daizen (Sakura Illustrated: Complete) (Shinchōbunko) (1985)

Hiroki Azuma, Otaku: Japan’s Database Animals, first published in 2001, translated by Jonathan E. Abel and Kōno Shion (University of Minnesota Press) (2009)

Jean-Marie Bouissou, Manga: A Historical Overview, in Manga: An Anthology of Global and Cultural Perspectives, edited by Toni Johnson-Woods (Continuum) (2010)

Paul Gravett, Manga: Sixty Years of Japanese Comics (Laurence King Publishing) (2004)

Sharon Kinsella, Adult Manga: Culture and Power in Contemporary Japanese Society (Curzon) (2000)

Akira Oze, Boku no mura no hanashi (The Story of My Village) (Kōdansha, Morning K.C.) (1992-94)

Tsurumi Shunsuke, A Cultural History of Postwar Japan 1945-1980, first published in 1984 (KPI) (1987)

Naoki Yamamoto, Red 1969-1972 (Kōdansha) (2007-14)

Further reading:

Mary A. Knighton, The Sloppy Realities of 3.11 in Shiriagari Kotobuki’s Manga, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 11, Issue 26, No. 1, June 30, 2014

William Marotti, Political aesthetics: activism, everyday life, and art’s object in 1960s’ Japan, Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, Volume 7, Number 4 (2006)

William Marotti, Money, Trains, and Guillotines: Art and Revolution in 1960s Japan (Duke University Press) (2013)

Matthew Penney, War and Japan: The Non-Fiction Manga of Mizuki Shigeru, The Asia-Pacific Journal, September 21, 2008

Rumi Sakamoto, “Will you go to war? Or will you stop being Japanese?” Nationalism and History in Kobayashi Yoshinori’s Sensoron, The Asia-Pacific Journal, January 14, 2008

Reiko Tomii, Akasegawa Genpei as a Populist Avant-Garde: An Alternative View to Japanese Popular Culture, KONTUR, Number 20 (2010)

Yuki Tanaka, War and Peace in the Art of Tezuka Osamu: The humanism of his epic manga, The Asia-Pacific Journal, 38-1-10, September 20, 2010

Notes:

1. Bouissou, p.26

2. Gravett, p.41

3. Ibid., p.42

4. Kinsella, pp.30-31

5. Tsurumi, p.112

6. Kinsella, p.36

7. Ibid., pp.142-143

8. Gravett, p.9

9. White Paper on Police, 1975, p.371

10. Concerned Theatre Japan (Volume Two, Number Two) (1971), p.16

11. Concerned Theatre Japan (Volume One, Number Tree) (1970), p.33

12.

https://www.cjspubs.lsa.umich.edu/electronic/michclassics/online/books/concerned.php (Retrieved March 14th, 2015)

13. Akasegawa, p.28

14. Kinsella, pp.185-186

15. Ibid., p.149

16. Ibid., p.105

17. Azuma, p.28

18. Ibid., p.35

WILLIAM ANDREWS

extremely informative,as usual……really looking forward to getting my hands on your book!

LikeLike

I was just handed a Zengakuren leaflet which *appears* to be pro-ISIS. If you have a way to obtain these I recommend checking it out.

LikeLike

@Avery

Are you referring to this November 18th flyer?

Click to access 5dbb0ffa111189a430f099850153f09e.pdf

It is calling for air strikes in Syria to cease and for international solidarity in preventing war (i.e. France, the United States and Japan joining up to wage war in Syria against IS).

Zengakuren is anti-ISIS, like its parent organisation. Chukaku-ha organs have documented the little-reported struggle of unions and labour in the Middle East under the yoke of Islamic State (and others). However you may feel about its militant methods over the years, Chukaku-ha has a long pedigree as anti-war campaigners (Anpo 1970, anti-Vietnam, etc).

LikeLike

Just got another great pamphlet from them. I can’t doubt the purity of their anti war credentials — they are accusing the Communist Party of being pro-war! And on logical grounds, too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is a really interesting read William. I am going to be working on Akasegawa with some of my students this year and it’s great to have somewhere to send them for info on Sakura-gahō. Cheers!

LikeLike

@Chris

Many thanks for reading. There is actually lots more to say about Sakura-gahō; its issues and the various spin-offs run into the hundreds of pages. I recommend downloading the PDF of Issue 2.2 of Concerned Theatre Japan, which has an English translation of some of Sakura-gahō.

https://www.cjspubs.lsa.umich.edu/electronic/michclassics/online/books/concerned.php

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Audible Anarchism.

LikeLike