A spectre is haunting Tokyo, but it’s not the spectre of communism: it’s a famous movie monster. Fresh from a recent Hollywood remake and with a homegrown film also on the way, Godzilla is very much back in town, literally. The iconic beast now peers over the citizens in the streets of Tokyo as the star attraction of an expensive urban development. The 12-foot Godzilla looms from a rooftop on the Shinjuku Toho Building, which opened in April in Kabukichō, the entertainment district a short walk from Shinjuku Station. Technically it’s only Godzilla’s head but at a glance, it almost appears as if the monster is bursting through the skyline from above to launch its atomic breath at innocent movie extras.

Godzilla peers over the Kabukichō landscape

Photo: William Andrews

The complex includes a Tōhō cinema (Godzilla is a Tōhō franchise) and the 970-room Hotel Gracery Shinjuku (one of several recent plush new hotels in Shinjuku), which has been especially designed with the replica head in mind. There are two “Godzilla View” rooms, offering an exclusive eye-level vista of the destructive beast, and, for the serious fans, the Godzilla Room is even decked out with an interior filled with elements from the Godzilla movies, complete with Godzilla hand reaching through the wall to grab you. Anti-nuclear power protestors, who are still very active in Japan more than fours years on from the Fukushima disaster, might point to the irony of such architectural kitsch based on a monster created by nuclear radiation. However, the appearance of Godzilla in the cityscape of Tokyo’s Shinjuku district illustrates more general changes taking place in the area.

Long a no-go area for many due to its reputation as a den of vice, Kabukichō is getting a facelift. A cheesy “robot restaurant” opened in 2012 and pulls in a largely foreign crowd eager to watch dancers cavort with a range of large machines. Though the pimps and sex clubs are still only a stone’s throw away, sin city is now in danger of becoming a theme park. The transformation has been compared to how Times Square was cleaned up; it’s no longer the place to go for drugs and porn, but instead to snap a photo of a famous New York landmark or two. Likewise, Kabukichō’s basic cosmetic is morphing and tourists and casual shoppers are venturing where few dared before, drawn in by the Godzilla statue that lights up at night. In the main Kabukichō avenue, a strip where once touts would try to entice men with offers of sex with prostitutes, today stand gaggles of Chinese visitors posing with selfie sticks to grab a shot with Japan’s most famous monster.

A sign on the right warns visitors about touts and scams in the area

Photo: William Andrews

Inbound tourism from Asia is changing everything and retail tills are ringing loud across Shinjuku and Ginza. According to the Japan National Tourism Organization, there were 1.76 million arrivals in April – a new record. Leading the pack were the 405,800 visitors from China. Shinjuku also awarded Godzilla honorary citizenship at a special ceremony in April and the reptilian sexagenarian is now the ward’s tourism ambassador. This is a strange move for a number of reasons, not least considering the amount of damage Godzilla has inflicted on Tokyo on celluloid.

Anyone familiar with Japanese cinema from the 1960s will know Shinjuku’s renown as a site of post-war Japanese counterculture. Recent years have seen it supplanted by the likes of other districts to the west, but these are potentially at risk. Shimokitazawa is currently undergoing a methodical sanitisation by the Odakyū Group, redeveloping the grungy neighborhood’s station vicinity and in the process removing a swath of the independent restaurants and shops for which Shimokita is loved. While these west Tokyo areas remain hubs for counterculture and subcultures, and have attracted plenty of attention from overseas too – especially Kōenji and Nakano Broadway – Shinjuku’s counterculture credentials have stayed more or less constant, for now at least.

As the post-war avant-garde arts evolved, Shinjuku became a major home for the angura (underground) scene. Hanazono Shrine sits in a quiet oasis, a leafy path separating it from Kabukichō proper. The shrine’s grounds were one of the makeshift outdoor venues where Jūrō Kara staged his legendary theatre performances from the latter half of the 1960s, often sparking controversy and even police intervention. Kara is also part of the cast of Diary of a Shinjuku Thief (1969), Nagisa Ōshima’s paean to counterculture, centring on the eponymous Tokyo district.

Hanazono Shrine today

Photo: William Andrews

Let’s imagine we are in Shinjuku, circa 1969. It was a place where every corner seemed about to come alive with a performance. Beatniks, fresh from hitchhiking across the land, drifted from bar to gallery to demo to commune to a tiny apartment and back to the bar again. It was hyped up by the media as an “erotopia” of sex, fūten (a type of Japanese layabout or hippie), bikers and dancers. The milieu was addictively alternative. A parade of hippies might be playing guitars and chanting mantras, bedizened in flowers and beads, while “folk guerrillas” strummed protest songs at the station’s West Exit plaza. Students would be on the streets collecting donations for their latest crusade. Shinjuku became a thousand immortalising snapshots, from the pageantry of Kabukichō whores, Ni-chōme drag queens and partying kids captured by Katsumi Watanabe’s lens, to Shōmei Tomatsu’s 1969 series of images of street rebellion, simply entitled Oh! Shinjuku. Oh, Shinjuku indeed! It is all too easy to get carried away in the revelry of nostalgia that a place creates, especially when it has been helped out by artists and the mass media.

The facts speak for themselves: Shinjuku was the location of massive protests that turned into riots in October 1968 and 1969, led by demonstrators against the Vietnam War, though ultimately multiple issues (the campus strikes, Okinawa, the US-Japan mutual security treaty) converged in the violence. On Christmas Eve 1971, a bomb exploded outside a police substation not far from the august Isetan department store, injuring several. The leader of the militant cell responsible was imprisoned for life.

But all that was the past. The average Japanese citizen today is a political nebbish, right? If I had a dollar for every time I heard the old saw that the Japanese, after a flurry of radicalism in the late 1960s, settled down to unadulterated consumerism and capitalism in the 1970s, I would be a rich man. If it is the more frustrating because it is not wholly untrue: reality is more ambivalent.

A protest being held outside Shinjuku Station East Exit

Photo: William Andrews

In spite of the relentless throb of consumerism and retail tills, the east front of Shinjuku Station remains a common choice of location for political rallies and marches to start. The west side of the station is quieter, more grey. It is now dominated by the sheen of modern hotels, malls and the Tokyo Metropolitan Government Building. After the closure of the Yodobashi Purification Plant in 1965 (a small section remains in Shinjuku Chūō Park), the development of the district began to swell in the early 1970s. The Keio Plaza Hotel opened in 1971. In 1974, three skyscrapers were completed: Shinjuku Sumitomo Building, KDDI Building and Shinjuku Mitsui Building.

Ironically, it was the station’s underground plaza — finished in 1966 — that seemed to herald in this evolution, though not before it also transformed into a brief yet passionate liberated zone. The folk guerrilla gatherings that took place in the underground plaza every Saturday over the spring and summer of 1969 were eventually suppressed by the police and the main musicians arrested; the period lives long in the memory of participants but actually lasted only a few weeks. Today one of the veterans, Seiko Ōki, continues to go to Shinjuku Station’s West Exit every Saturday, where she holds a non-musical, silent and dignified demo. With peers, they hold placards protesting war and the US military bases in Okinawa. They do it for one hour above ground, followed by another session in the underground plaza where Ōki used to sing to thousands. There are no guitars or crowds this time, but in a sense the same spirit lives on.

Seiko Ōki (left) with other anti-war protestors at Shinjuku Station West Exit

Photo: William Andrews

Not far from Ōki’s irenic weekly vigils, one quiet Sunday afternoon in summer 2014 on the south side of the station a man attempted self-immolation while sitting on the girder of a pedestrian walkway in protest at the government’s attempts to change the Constitution. His conflagration was filmed in horror by diners watching from windows of the restaurants in the mall adjacent to the walkway.

The 1956 anti-prostitution laws led to the decline of the overt akasen red light districts in Tokyo, and this left a gap in Ni-chōme in Shinjuku that sexual subcultures eventually filled. Conveniently tucked 10 minutes’ walk away from the station (and prying eyes), you could have another life in Ni-chōme, even if you were married. Japan, mostly free of religious influence on public life, did not have anti-sodomy laws such as those in the UK, but homosexuality still had to be pigeonholed and kept to one side. This is perhaps why, despite Tokyo’s massive size, proportionately its gay neighbourhood is tiny.

That being said, Ni-chōme is vibrant. It is sometimes claimed to boast 300-400 bars, clubs and other establishments. It is also one of the best places for foreigners to drink because many bars are open, literally spilling out onto the street, whereas regular drinking holes in Japan tend to exist behind closed doors inside uncertain buildings. However, change is afoot. Police have been cracking down on proprietors who don’t have the right license; this might mean arrest just for letting your patrons sing karaoke. A billboard in Ni-chōme regularly advertises safe sex but in December 2013 the then current version of the poster was deemed inappropriate. Even though it was an illustration, rather than a photograph, the depiction of a muscular male figure was apparently too sexy for the good citizens of Shinjuku simply because he was shirtless (have these people looked at the adult magazine section in a convenience store?). The poster was censored and replaced with a fully clothed man.

An HIV awareness poster in Ni-chōme

Photo: William Andrews

More generally, higher property prices are driving some places out of business, plus the nationwide crackdown on dancing in clubs also contributed to a general downturn in the neighbourhood. A string of nightclub incidents triggered a spike in police attention on those breaking the “no-dancing” law (which traces back to the anti-prostitution measures introduced during the US occupation). Overlooked for a long time, the police offensive affected clubs and music culture around the country, including Ni-chōme, and was finally lifted in 2014. Hopefully people can get back to partying without fear of the music being turned off.

On the fifth floor of a building with one of the steepest, narrowest staircases imaginable sits matchbaco, a small gallery that opened last year. It tends to host a cosmopolitan, gay-friendly crowd, and gallerist Kenichi Nakahashi’s choice of location, on the edge of Ni-chōme near the park Shinjuku Gyōen, was deliberate. “There are always people in Shinjuku,” he says, “and it’s a good mix of people. It’s a very real place.” Nakahashi also notes one of the defining characteristics of Shinjuku: its contrasts. There are the recent chain stores like H&M alongside the older department stores like Isetan, plus “unsavoury” places such as Kabukichō and Ni-chōme.

His tiny gallery is a “box of matches” that offers sparks of encounters. He started the venue after he recovered from an illness and decided to dedicate his life to doing something more fulfilling than a life in the rat race. He programmes shows that vary widely in terms of media and genre, but all his artists share a sense of humanity and interest in physicality. They confront hidden suffering and pain, though sometimes the approach is pop, at other times it is darker.

My ramble through the area continues. What do books about insect-eaters in Tokyo, drug culture, coffee economics, shibari rope bondage, Marxism, Japanese student activism, sex museums, and a memoir by Fusako Shigenobu have in common? They are all among the plethora of books and materials stocked at Mosakusha, a hub for newsletters and organs for activists and political groups. Located only a few streets away from matchbaco, it was opened in 1970 by Masahiko Gomi, a non-sectarian activist from Waseda University, a major loci for Japanese radical politics in the 1960s. Incongruously, it borders the refined greenery of Shinjuku Gyōen and just opposite is repudiated by an expensive European cuisine restaurant. The bookstore resembles a hut or shack, its outside wall occupied by a board overloaded with flyers for events, almost as if they are growing off the wooden walls like foliage. The aisles, all four of them, are so narrow you practically have to climb onto the lower shelf to get past someone. The staff are, if not quite surly or unwelcoming, then certainly taciturn, unforthcoming with their expertise or the usual niceties demanded of the service industry by Japanese’s complex system of respect language.

Mosakusha

Photo: William Andrews

Photo: William Andrews

The bookstore is a co-operative mostly selling minikomi – “mini communication” newsletters, magazines or books, typically self-published, that cannot gain circulation on the mainstream publisher-distributor-bookstore distribution system in Japan. Mosakusha, whose name literally means “house for searching”, retains its non-sectarian policy: everything is represented, from right to left, anarchist to ultra-nationalist. This gives quite a frisson to see the official newspapers of factions that have in the past murdered each other stacked up side by side. Mosakusha is a rare survivor of the underground bookstores from the height of the New Left movements in Japan. It still feels very underground in a wonderfully haphazard way, even in these days of cultivated hipster thrift shops.

Not surprisingly, it has crossed the line between retailer and activist, and faced the consequences. Two members of Mosakusha were once indicted for possessing licentious publications with intent to sell them. It was also involved in publishing pamphlets supporting the printer harassed by police for printing a notorious New Left booklet that advocated the destruction of Japanese society. Today Mosakusha exists in a double bind; its clientele includes fringe figures, the curious and activists, but also the very agents of the state that has tried to suppress their work. The security police are regular customers who have to purchase the organs of the various factions to keep abreast of their latest ideologies and campaigns.

Mosakusha is one of the few places where these organs are sold. In theory, if you bring yours along, they will sell it for you – regardless of affiliation. In this sense, it is a quite unique space offering a bird’s eye view on the full range of leftist and other movements in Japan. It remains in rude health and alongside yellowing paperbacks and the dense piles of newsletters, its more accessible catalogue of unusual manga, liberal magazines and edgy books also bring in new customers. Sometimes couples on a date passing by on their way to the Gyōen gardens poke their heads in to this Aladdin’s cave of radical delights. Watching their eyes trying to make sense of it all is can be an amusing pastime in its own right.

Head over into Ni-chōme proper and you can find Café Lavandería. The easygoing venue is the second generation of a site that used to exist in Iidabashi. “The space is the important thing to have. People need somewhere to come together,” recalls Toshihide Fujimoto, one of the team who run the café. Its present incarnation opened in 2009 in a building owned by Gen Hirai, a writer and critic, who also runs a gallery upstairs and grew up in the building. It was previously a laundromat, hence the name, converted into Spanish, and the original business’s logo remains on the door.

Café Lavandería

Photo: William Andrews

Photo: William Andrews

You might wonder what is so special about a café in Shinjuku; the locale is heaving with coffee shops and the like. But Lavandería is run by a collective who decide the events and plan them together. Currently there are 14 members, including a non-Japanese one. But anarchism and complete egalitarianism is difficult in practice when it comes to operating a business. Since the others have their own jobs, ultimately Fujimoto and his wife end up being the “main” people managing the space.

Lavandería is often called an “anarchist café” but Fujimoto himself is slightly hesitant with labels. “I’m nervous about using the word ‘anarchist’. I don’t mind if people call us an ‘anarchist café’ but I don’t call it that myself. Anarchism is tricky. Even communism is easier for people to understand, since there’s still a system.” Anarchist or not, the basic two tenets of the space are clear enough in the Spanish name and its slogan: Música y Anti-Capitalismo. “If you only have talks and discourse, then only leftists come,” Fujimoto explains. The music is a way to make the space more accessible, so you’re not just preaching to the converted.

Directly opposite is Goldfinger, a lesbian bar (“women only”, firmly declares the notice on the door). After all, we are in Ni-chōme. Lavandería is also home to four cats (all ginger), making it a de facto “cat café”, which are popular in Japan. With its bookshelves across one wall lined with beatnik titles and trendy anti-globalisation tomes (English and Japanese), it is tempting to discard it as a place for champagne socialists – to be accurate, champagne anarchists – but there is sincerity in the way it is run. The collective are allowed to manage and use the space for events that take their individual fancy if approved by the group. It makes for an eclectic schedule of music, talks and screenings, but a common mentality pierces through it all: freedom, music, the nomadic, polemic, anti-establishment. Most events are free of charge to attend (a novelty in itself in Japan) and with a non-enforced pay-what-you-can policy in the form of a collection bowl.

Musical instruments decorate the walls, a tiny disco ball hangs from the ceiling, and the clock is always 10 minutes fast (to remind people they need time to get back to Shinjuku Station). There are flags: a Palestinian one and another for Confederación Nacional del Trabajo. The menu includes Zapatista coffee, grown in Mexico, roasted in Hamburg, and then shipped to the café. The pricing for the coffee is ¥300-500 – you pay what you can afford or think the coffee is worth.

The Latin flavour of the space is unmissable, from the name to the Spanish lessons they host regularly. “I want to remove ‘English’ from here,” says Fujimoto. This isn’t rooted in discrimination against Americans or Britons. “All those big corporations in Japan have been saying they are going ‘all-English’ – having meetings only in English and so on.” Fujimoto is referring to companies like clothing retailer Uniqlo and online shopping giant Rakuten, who have made public announcements about their internal “Englishization”. “The Japanese think that they are ‘international’ if they speak English. But actually the Spanish-speaking population is equal to the English-speaking one.”

Far from being full of young hipsters, the demographic skewers older much of the time, though depending on the event, it can draw a pretty mixed crowd, a ragbag clientele of misfits, hippies, music-lovers, globe-trotters, and gadflies. It’s no surprise that Noam Chomsky turned up here when he visited Tokyo to do some lectures at Sophia University. His autograph modestly adorns the wall under the counter, alongside many others.

Irregular Rhythm Asylum

Photo: William Andrews

Photo: William Andrews

About seven minutes’ walk from Lavandería, on the third floor of a nondescript building in Icchōme down a small alleyway, is Irregular Rhythm Asylum. Marketing itself as an infoshop, it sells zines, music (a lot of punk) and books. While some of these are trendy tomes, there is a wealth of obscure titles, plus a large collection of anarchist materials. It is run by Keisuke Narita, who can invariably be found relaxing behind the counter of this haven for low-fi delights. Irregular Rhythm Asylum was born out of Narita’s experiments with creating zines and a distro (zine distribution centre) in 2004. While ostensibly a shop, it is actually really just a meeting point, a tiny space for exhibitions, events, and exchange. Narita makes his living as a graphic designer so can afford for IRA to be quiet during the daytime. This is typical of the mellow, laconic anarchism that emerged in the Heisei Period (1989-present), where Japan’s “lost decades” have cultivated a generation of under-forties who no longer care for the corporate ladder but who also don’t want to pursue the fierce strain of radicalism that the Baby Boomers indulged in during the 1960s and 1970s.

There is always a danger of romanticising counterculture spaces or overstating their importance. Foreign observers in Japan may be particularly guilty of this, from Donald Richie to Alan Booth. Even the very act of describing or examining a place is to make it exotic and intriguing. As soon as, to borrow an anachronism, you put pen to paper, somewhat inevitably you glamorise. That said, you cannot help weeping with joy when you see such ramshackle places that refuse to play by the rules of consumerism and neoliberalism. At times it can seem that every square meter of Tokyo is undergoing or about to undergo development. Every season brings the opening of a new mall or commercial complex, and the construction work will accelerate as we get closer to the 2020 Olympic Games.

Like it or not, though, Shinjuku is changing and its counterculture, past and present, faces challenges if it is to survive intact.

Golden Gai is often extolled as one of Tokyo’s most charming spots. Occupying a warren of streets between Hanazono Shrine and the main part of Kabukichō, the passageways house dozens of microscopic bars in two-storey buildings. It grew out of the former red-light district (of course, merely repackaged and camouflaged when prostitution became illegal), the streets are quiet during the daylight hours but come alive with the sounds of laughter and drinking when night falls. These alleys were where you were likely to find the late leftist film director Kōji Wakamatsu propping up a bar with a beverage, surely not his first, in hand. The cigarette smoke is eternally thick in the air of these bars. A walk along the streets, though, makes you more voyeur than flâneur, as Kabukichō’s seedy world is always only ever just around the corner, with its hawkers, Chinese streetwalkers, and love hotels. Today Golden Gai is as much for overseas tourists as regulars. A younger generation has moved in as both patrons and owners age, making the bars more open and inviting, though it has so far resisted full gentrification. It still has cultural associations too (there are plenty of theatre posters on the walls); the bars remain shambolic and fused with 1960s lore, if rather conveniently “themed”: there is the retro video game bar, the jazz bar, the avant-garde theatre bar, and so on. And there are rumours that even Golden Gai’s days are numbered as Kabukichō is redeveloped.

Golden Gai, Shinjuku

Photo: William Andrews

Photo: William Andrews

Photo: William Andrews

Photo: William Andrews

While the committees may hesitate over nostalgic Golden Gai, Sanchōme, the bustling area between Ni-chōme and the immediate station east side vicinity, gets no such reprieve. It is conspicuously being refined: the ramshackle and independent restaurants are disappearing, replaced with hotels and oysters and wine bars with a uniform chic. For now at least, the famous Rakugo theatre seems safe. This is all a corollary of the expansion of the Shinjuku-sanchome Station’s subway lines, meaning more people can bypass the main Shinjuku Station, with its anonymous high rises filled with monotonous floors of eateries and shops. The 620-room APA Hotel Shinjuku-Kabukichō Tower is also scheduled to open this September, furthering the gentrification of the Kabukichō district.

Hanazono Shrine still stages Jūrō Kara’s “red tent” performances, over four decades on from their first appearance, but it feels stamped with approval now. There is no longer anything sacrilegious or dangerous about these “guerrilla” plays. After all, the public sphere has been given to the consumers. Shinjuku featured Tokyo’s first experiment in pedestrianised zoning and it lasts to the present: like in many districts such as Ginza and Akihabara, the weekends see the main road blocked off to traffic so people can roam free. However, there are signs prominently displayed stating that performances and hawking are forbidden. Public space is controlled.

This is because the authorities want an unblemished Shinjuku, a place whose only function is for shopping, eating and drinking. Shinjuku ward also banned “touting” and “soliciting” in 2013 in an attempt to stamp out the notorious reputation Kabukichō has for tricking men out of their money with the temptation of women (so-called bottakuri, scams with heavily padded bills). Public announcements are made warning people not to believe the pimps who offer them sex with attractive women. Police have made a show of raiding certain bars and citizen complaints about bottakuri has increased ten-fold since last year, but quite how far their crackdown is truly penetrating is debatable.

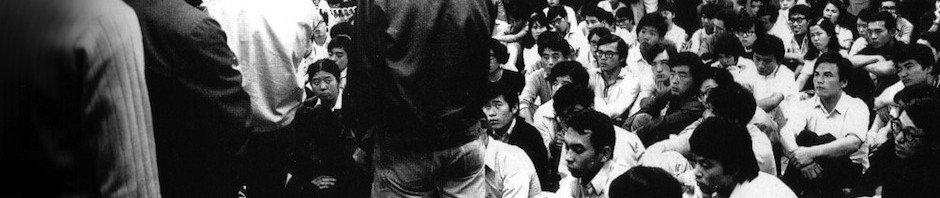

A famous image of Dadakan (Kanji Itoi) running with a “Do not kill” anti-war poster.

As the city moves closer to hosting the 2020 Olympics it will keep on trying to “clean up” its less agreeable elements. Ahead of the 1964 Games there was a similar push to scrub Tokyo of its imperfections. This was derided at the time by artists such as Hi-Red Center, who staged a stunt whereby they dressed up in lab coats and set about ridiculously sprucing up the streets of Ginza with brooms. One of the first events I attended at Café Lavandería was an odd assortment of various mini musical performances. The warm-up act consisted of a man rambling anecdotes, eventually riffing into a musical skit and stripping down to his underwear. Intriguingly, this comic, as random as he was, looped back to 1960s counterculture. His t-shirt was printed with a photograph of the performance artist Dadakan holding a placard saying “korosu na” (Don’t kill), the slogan of the anti-Vietnam War protests. Dadakan, aka Kanji Itoi, is perhaps best known for pretending to be an Olympic torchbearer in 1964 and running naked through the streets of Tokyo (for his troubles he was committed to a mental hospital). Come 2020, perhaps we’ll see some similar exploits in Shinjuku — if we’re lucky.

WILLIAM ANDREWS

This is wonderful, William. Thank you so much for this blog–it is unique, invaluable–and congratulations on your new book! Wow! Marilyn

LikeLike

Great work.

LikeLike